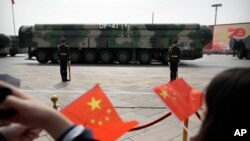

American researchers using commercial satellite imagery say China appears to be significantly expanding the number of launch silos for its arsenal of intercontinental range ballistic missiles, raising fears that nuclear weapons will become a new issue of contention between Washington and Beijing.

Using images provided by the satellite imaging company Planet, two researchers from the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey (California) found that China is building 119 silos in the desert of the northwestern province of Gansu.

Jeffery Lewis, one of the researchers, told VOA that development is likely for China’s DF-41 ICBM, which is believed to be capable of carrying multiple nuclear warheads. With an estimated range of nearly 7,000 kilometers and possible capability to carry up to 10 warheads, researchers believe the missiles can reach targets in the United States.

“We believe China is expanding its nuclear forces in part to maintain a deterrent that can survive a U.S. first strike and retaliate in sufficient numbers to defeat U.S. missile defenses,” Lewis said in a summary of findings provided to VOA.

In response to the findings, the State Department said that the U.S. is concerned about China’s rapid expansion of its nuclear capabilities.

"These reports and other developments suggest that the PRC's nuclear arsenal will grow more quickly, and to a higher level than perhaps previously anticipated," State Department spokesman Ned Price said in a briefing on Thursday.

He called the buildup “concerning.” “It raises questions about the PRC's intent. And for us, it reinforces the importance of pursuing practical measures to reduce nuclear risks," he continued, "We encourage Beijing to engage with us on practical measures to reduce the risks of destabilizing arms races - potentially destabilizing tensions."

The Chinese Embassy in Washington did not respond to a request from VOA for comment.

In 2020, the Department of Defense estimated that China had around 100 ICBMs, and will double that number in the coming years.

The researchers said the 119 new silos are spread across approximately 1,800 square kilometers near Yumen, a city in Gansu province, with each spaced approximately 3 kilometers apart. Images show that construction began in March 2020, but most building was done since February 2021, “suggesting an extremely rapid pace of construction over the past few months,” the summary said.

Timothy Heath, a senior international and defense researcher for the policy research group the RAND Corporation, told VOA by email that the silos raise the credibility of China’s nuclear force.

“It shows China intends to expand its inventory of nuclear weapons. This means China is raising the potential risk and cost of escalation in any conflict along China’s periphery,” he said.

Worst case scenario analysis

Other researchers warn that the calculations might be worst case scenario assumptions. James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said there are a lot of questions to ask before concluding that China is expanding its nuclear arsenal at such rapid speed.

In an article published in The Washington Post, Acton said that there are still debates regarding how many warheads China’s missiles can carry. He also pointed out there is a possibility that China is mirroring the approach called the “shell game” designed by the United States in the late 1970s for basing some of its missiles.

During the Cold war, the United States created a plan to build multiple launch shelters for each missile, 23 for one to be exact. The missiles were regularly moved among silos to make it impossible for the Soviet Union to target U.S. land-based ICBMs. The plan was adopted by the Carter administration but was later changed by the Reagan administration.

Lewis agreed that that is a possibility. “China likely has similar concerns about the survivability of silo-based ICBMs, and may rotate a smaller number of ICBMs among a larger number of operational silos,” he added.

Acton also pointed out that China still has a relatively small nuclear arsenal compared to the U.S. According to the Pentagon, China has a warhead stockpile in the low 200s. “For comparison, the United States possesses around 3,800 nuclear warheads, of which around 1,750 are deployed,” Acton wrote.

The U.S. has repeatedly reached out to China for negotiations on nuclear arms. In May, the U.S. disarmament ambassador, Robert Wood, said at a U.N. conference that China continues to resist discussing nuclear risk reduction bilaterally with the U.S. China's envoy, Ji Zhaoyu, responded by saying that Beijing is ready to engage, but only “on the basis of equality and mutual respect.”

Heath, from the Rand Corporation, said that in view of the new developments, the U.S. may seek to press for arms control talks with China, but it's doubtful China will accept such controls given the small size of its nuclear arsenal. “The U.S. may also need to build more anti-missile defenses,” he said.

Acton said a quid pro quo might work. “If the United States wants to engage China in arms control, the kind of idea that I think is worth exploring is a quid pro quo, by which the U.S. agrees to limit its missile defenses, for example by agreeing not to develop or deploying missile defenses in space, in return for China agreeing not to produce any more nuclear material with which it could augment its arsenal,” he said in an analysis video posted by Carnegie.