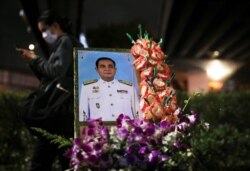

Thailand’s highest court on Wednesday acquitted Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha of wrongdoing linked to his stay in an army house long after he retired from the military, a case that could have seen him removed from office and offered a way out from a political crisis engulfing the kingdom.

Pro-democracy protesters, who demonstrated in the tens of thousands to press for Prayuth to resign, immediately gathered at a major Bangkok intersection after the constitutional court’s ruling in favor of the prime minister.

The nine-judge bench unanimously decided Prayuth’s prolonged stay at a taxpayer-funded army residence after he retired as army chief in late 2014 was neither a conflict of interest nor violated “any laws” and therefore “he will remain prime minister.”

Prayuth, a former army chief who is the focus of the protesters’ anger, took power in a 2014 coup vowing to defend the monarchy and bring peace and unity to a divided nation.

Six years later, Thailand is split like never before, with the once untouchable monarchy now at the center of calls for reform.

The court ruling was met with anger by the thousands who rallied in a Bangkok suburb into Wednesday night, chanting “Down with dictatorship, long live democracy,” and listening to speeches from a stage framed by a big screen showing an animated version of the court bench with ducks in judges’ wigs.

“The court doesn’t care about anyone but their own camp,” Piraya, 25, told VOA, giving only one name. “They only care that their people stay in power. Where is the justice?”

The constitutional court has played the referee in Thai politics throughout the last 14 years of turmoil, which has seen two coups and endless rounds of rival street protests.

Critics say its rulings are one-sided, taking out three pro-democracy prime ministers in that time — as well as the progressive party of the hero of the democracy movement, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, while, they say, going soft on establishment figures brought before their bench.

“Over the past 10 years the court has subverted democracy too many times,” protest leader Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak told the rally, which included giant inflatable rubber ducks — the emblem of the movement used to fend off police water cannons — passed over the heads of the crowd as the royal anthem was played over speakers.

Escalation

In addition to the resignation of the embattled Prayuth, the protesters want a new constitution to be written, removing power from the army and King Maha Vajiralongkorn.

Anger is building with no signs of serious government compromise.

The protesters accuse the king, who ascended the throne in 2016, of creeping towards absolutism by using the crown’s wealth as a private piggy bank, while shifting elite army units under his direct command and moving political pieces around from behind the scenes.

After six years of faltering leadership, Prayuth is deeply unpopular, increasingly even among his erstwhile backers in the conservative establishment.

But he has repeatedly dismissed calls for his resignation.

Prayuth’s legal reprieve “means we can be sure to see an escalation on the streets,” said Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang, constitutional law scholar at Chulalongkorn University.

But the prime minister appears unable to defang the youth-led protest movement, which has so far kept coming out, despite waves of legal charges, police water cannon and skirmishes with royalists.

“So the conservatives ... the establishment may need a new face to represent them and manage their interests as well as to suppress the pro-democracy movement,” Khemthong added.

But in a deeply polarized nation, there are few prominent figures with credibility across the pro-army and pro-democracy camps.

The king has yet to directly address the protesters, instead answering a question on their demands by insisting the monarchy loves “them all the same.”

Since then, at least five core leaders of the movement have been charged under Thailand's strict lese majeste laws, which carry up to 15 years in jail per conviction for insulting, defaming or threatening the monarchy.

Several others have been summoned by police, as the law is used to squash the graffiti, placards and chants directed at the king by a boisterous — yet so far peaceful — street movement.

Prayuth recast himself as a civilian leader after 2019 elections held under rules critics say favored the military-aligned parties at the expense of the pro-democracy camp.

On taking office, he appointed 250 senators — a key clause of a new constitution drafted by the junta — giving him a parliamentary majority and a house stuffed with ex-generals and army loyalists as lawmakers.

But critics say he has bungled the economy, hooking it onto expensive 20-year investment plans with little public scrutiny, while the country now battles the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic.

In a country that has seen 13 coups since 1932, there are fears another military intervention may be near to end the protests.