China’s plans to build railways and roads that will cut across the Himalayan mountains into Nepal are being watched closely: The ambitious projects could draw Beijing deeper into the South Asian region increasing its strategic influence close to Indian borders.

While India is wary about the development that China is promising Nepal under its Belt and Road initiative, opinion is divided in the tiny country wedged between the Asian giants on whether it will bring a boon or drive it into debt.

The highlight of the 20 point agreement signed during a landmark visit by Chinese president Xi Jingping to Nepal last week was a Himalayan corridor: a feasibility study for a trans boundary railway that will run from Tibet to Kathmandu and eventually to Lumbini, a town close to the Indian border and a tunnel road to be built through the Himalayas to connect Kathmandu to Kerung, a town near the Chinese border.

“This is a paradigm shift in our history. Until today we were much more looking to the south, now after Xi Jinping’s visit our north is also opening up,” says Mrigendra Bahadur Karki at the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu.

Landlocked Nepal, long a buffer between China and India, relies for its trade and transit routes through India on its south. But as the country looks increasingly to Beijing for investment amid a dramatic upswing in ties, China has pledged connectivity projects that will provide alternative routes and reduce its dependancy on India.

“We will develop a multidimensional trans-Himalayan connectivity network and help Nepal to realise its dream to transform itself from a landlocked country to land-linked country,” Xi said during his visit to Kathmandu, the first by a Chinese leader in 23 years.

Although previous governments were cautious about the Chinese offers amid concerns that they can drive countries into debt, the ruling Nepal Communist Party led by prime minister K.P. Sharma Oli is enthusiastic about getting on board the Belt and Road Initiative — increasing business with Beijing was one of the promises he made when he won in 2017. He has even reinstated a $ 2.5 billion hydroelectric project being built by a Chinese firm that was cancelled by the previous government citing irregularities.

The trans Himalayan rail project in particular has created much buzz in Nepal, which has been looking to reduce its reliance on New Delhi ever since India was blamed for tacitly backing a five month long blockade of its main trade route by ethnic Nepalese in 2015. The blockade created crippling shortages in Nepal.

The railway project that involves laying 72 kilometers of rail tracks through high mountain terrain to connect Tibet to Kathmandu is considered a massive engineering challenge — but there is optimism in Nepal that Beijing has the prowess to execute it.

Some say the connectivity projects will be a boon for Nepal, linking it to the huge Chinese economy, enabling swift movement between the two countries and turning the tiny nation into a transit hub for trade between China and India – the region’s two big economies.

But while many ordinary Nepalese are optimistic, analyst Karki underlines that there are also deep concerns about their affordability and a pushback against the Chinese projects. “China will provide us with soft loans. But Nepal is an economically poor country so there are questions whether we can pay back that loan or not. Nepali community, society, and political parties are divided on this,” according to Karki.

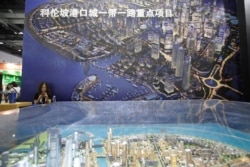

The example often cited is that of Sri Lanka, which after struggling to pay back for a Chinese-built port had to hand over its operations to Beijing, giving it a strategic foothold in the Indian Ocean close to Indian shores.

Analysts also point to China’s growing ideological influence in Nepal’s ruling party which along with a Chinese delegation last month hosted a symposium in Kathmandu on “Xi Jingping thought.”

For New Delhi, which has slammed the Belt and Road initiative as a form of colonization, the growing Chinese footprint in Nepal means that a country once firmly in its political orbit and sometimes referred to as its “backyard” is moving away, according to analysts.

“Considering the advantages India had in Nepal, for China to have that kind of influence does affect our standing,” says Manoj Joshi at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi. “When Chinese spend money in places like Nepal and Pakistan these are basically strategic actions, not necessarily economic ones.”

And while India has also promised to build a second rail link from its eastern state of Bihar to Kathmandu, critics say it has been slow in implementing connectivity projects in the South Asian region. “India does not have the wherewithal to take on China in terms of investing in projects, we don’t have the money to invest in projects,” points out Joshi.

Nepal’s only railway link so far is a 35 km track in its southern plains built by India. That is why analysts say, a tiny, economically backward country like Nepal that urgently needs to upgrade its infrastructure, is tempted by the opportunity provided by China.