TAIPEI, TAIWAN — The military government that seized power in Myanmar will get along well with its authoritarian neighbor China in the long term, despite historical misgivings, and grow closer if international sanctions isolate the Southeast Asian state from Western powers, observers say.

Myanmar’s military took control of the country Monday and declared a year-long state of emergency. Civilian de facto head of state Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel laureate, was detained in the power shift, prompting condemnation from Western governments.

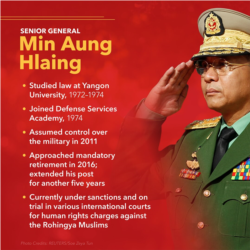

China might fumble at first to work with the new Myanmar leader, Min Aung Hlaing, because the military resents China’s involvement in a now suspended hydropower dam, cross-border shipments of Myanmar’s natural gas and other influence over the economy in the past 20 years, said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a political science professor at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University.

The professor said the two sides will eventually move forward because, unlike leaders in the West, China’s communist government feels no domestic pressure to condemn another authoritarian state.

“China is an all-weather friend, and you can see that when countries take an authoritarian turn, like Myanmar just did this week,” he said. "It's to China’s advantage because China does not have the democratic trappings and conditions on domestic governance, so it can be any kind of regime and it’s fine with China."

In Beijing, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said Monday his government was still trying to understand the “situation” in Myanmar. China is Myanmar’s “friendly neighbor,” Wang said as quoted on the ministry website, and “we hope all parties in Myanmar can settle disputes and maintain social and political stability by using the constitution and the laws.”

The military takeover stemmed from November’s parliamentary elections. The then-ruling National League for Democracy won in a landslide over the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party. The military, which ran Myanmar for nearly 50 years before the first democratic government emerged after 2011 under Aung San Suu Kyi, raised accusations of voter fraud.

China and Myanmar fundamentally got along before the recent events, though Myanmar was pursuing stronger ties with Japan and the West at the same time to offset Chinese influence.

On Monday, U.S. President Joe Biden vowed to take “appropriate action” and review possible sanctions against Myanmar. Australia, Britain, the European Union, India, Japan and Singapore have aired their own concerns this week about the stability of the Southeast Asian country.

Only Western governments feel “sentimental longings for democratization” in Myanmar, said Oh Ei Sun, Southeast Asia-specialized senior fellow with the Singapore Institute of International Affairs.

If the West imposes severe sanctions, then “maybe the Myanmar military will have no choice but to turn to China,” Thitinan said. Diplomatic isolation and the thirst for foreign investment to stimulate the impoverished country’s economy would drive Myanmar toward China, analysts say.

China became Myanmar’s biggest trading partner in 2011, replacing Thailand, with imports and exports worth $5.3 billion that year. China mainly ships raw materials and equipment for investment projects, while Myanmar sends minerals to China. A 2,200-kilometer land border facilitates their trade.

“Now after this coup we need to see how the junta handles ties with the United States,” said Huang Kwei-bo, vice dean of the international affairs college at National Chengchi University in Taipei. “That’s to say that if the United States adds pressure on Myanmar, then the junta will definitely think of a way to approach Beijing and tighten relations.”

Even without sanctions, today's political, trade and investment ties will probably keep their current course, analysts believe. Myanmar needs economic development aid to relieve poverty. China counts Myanmar as one in a network of countries around Eurasia where it's building infrastructure to open trade routes.

“China will remain Myanmar’s most important economic partner because it has the longest land border (and) it’s got the biggest investment,” said Alistair Cook, a senior fellow with the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

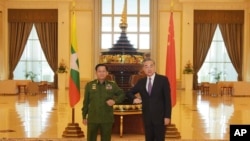

When China’s foreign minister Wang Yi recently visited General Min Aung Hlaing, now military leader, he indicated that China would “continue to back Myanmar in safeguarding its sovereignty, national dignity and legitimate rights and interests” on a “development path suited to its own national conditions.”

But the Myanmar junta’s relations with China will fray if festering border problems get worse under any military crackdown.

For example, both sides are grappling with a slew of new casinos that are located in Myanmar but heavily used by Chinese nationals from just across the border and known for spawning crime. China is building a border fence to curb the problem.

An end to fragile cease-fires between Myanmar’s government forces and armed ethnic groups living near China could further “influence China’s relationship” with the new junta if people start streaming across the borders, Cook said.