China's provincial government bodies are at the forefront of a massive online censorship campaign of unprecedented scope.

Two months after Beijing enacted a law effectively barring people from posting negative content online, state-run regional news outlets, internet providers and social media platforms are working interdependently to snuff out "rumors" online.

Announced in December, the Provisions on the Governance of the Online Information Content Ecosystem, which was implemented March 1, aims to "create a positive online ecosystem" and "preserve national security and the public interest."

By grouping online content into three categories — “Encouraged,” “Negative” and “Illegal” — the law criminalizes "dissemination of rumors," "disrupting economic or social order" and anything that "destroys national unity."

Some observers, however, say the law's vaguely defined criteria for "rumor-mongering" could be exploited to suppress reporting about COVID-19, which has already led to arrests and disappearances of multiple citizen journalists and whistleblowers.

“These 'rumors' tend to be [considered anything perceived as] very negative [toward] the government,” said Dr. Lauri Paltemaa, an East Asian Studies professor at the University of Turku in Finland.

“Many of these implicate the Chinese government, the military, as the black hand behind the [COVID-19] crisis,” he added.

But Steven Butler, East Asia program director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, says the law goes far beyond China's effort to control information about the outbreak.

“In China, a rumor is basically anything [Chinese officials] don’t like," he told VOA. "It’s not a question of what is truthful or not.”

Provinces at forefront

China's vast network of provincial internet information offices have launched a slew of rumor-busting sites since the new law came into effect.

Designed to function like fact-checking websites such as Factcheck.org and Snopes.com, the state-run sites are regionally focused clones of Beijing's piyao.org.cn, a national rumor-quashing site launched in 2018.

The concept of policing China’s digital sphere for misinformation or social media influencers who refuse to toe the official Communist Party narrative is nothing new.

A Beijing-run site, http://py.qianlong.com/, whose name translates as "websites jointly debunking online rumors,” has been active since at least 2013, while the 2015 launch of China’s Cyberspace Administration was one of President Xi Jinping's first major efforts to coordinate censorship online nationally.

The administration’s launch signaled the rise of so-called internet police who worked hand in glove with provincial police to hunt down and interrogate offending netizens.

Chinese search engine giant Baidu entered the fray in 2017, coordinating with the Ministry of Public Security and 372 "internet police departments" to aid in the crackdown. Via natural language processing, big data and artificial intelligence, Baidu’s search software was equipped to detect anti-government "rumors" and then flood Baidu-linked web sites, news sites and devices with alerts dispelling the so-called misinformation.

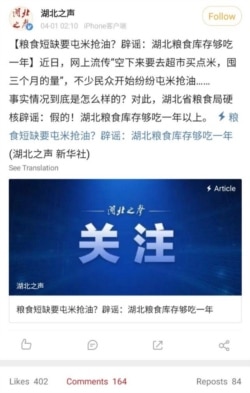

The March 1 law expands the scope of these operations, bringing major social media platforms like Sina-Weibo and WeChat into compliance, and planting rumor-dispelling verticals on regional state news outlet websites such as Anhui News and Hebei News Network.

Officials in neighboring Henan province recently issued a statement claiming to have online content reviewers working 24 hours a day to “regulate and control hot and sensitive public opinions.”

Netizens policing each other

With rumor-monitoring built into every facet of China's media ecosystem, user activity is constantly surveilled and is sometimes reported to authorities by fellow users.

In a March 1 statement publicly recognizing the new law, China Netcom, the country’s largest internet provider — and a wholly owned subsidiary of China Unicom, among the world's largest mobile service providers by subscriber base — said internet users and service providers “should come together to crack down on rumors online.”

“Censorship [on social media] is mostly not conducted by the government but by the people,” said Yue Jiang, a University of Maryland doctoral candidate and co-author of a 2019 study on Chinese social media, misinformation and censorship.

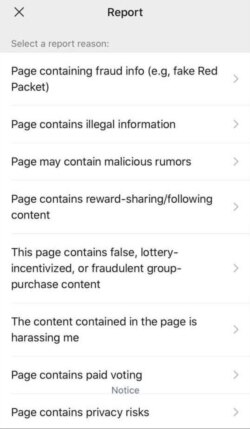

She also said most social media and news apps have dedicated sections for reporting rumors.

"If there are a lot of people reporting the same information, the information will be deleted,” she said.

Repercussions for spreading rumors can vary, from “warning rectifications” to closure of an account. Serious violators face punishment based on local laws, which, according to a recent New York Times report, can come swiftly.

“The internet police’s uncanny speed in finding people, who might believe they are hidden among the internet’s hordes of anonymous grumblers, is the result of billions of dollars in new spending on surveillance technology,” says the report, which describes an intensification of internet policing since the coronavirus outbreak.

In January, the report also states, internet police investigated 385 Guangxi residents for spreading rumors, along with 72 in Qinghai and 66 in Ningxia.

On February 28, Jiangxi’s Internet Information Office (IIO) said police detained a man for five days for spreading “false news” alleging 10 COVID-19 deaths in the province.

The Jiangsu IIO said 60 offenders in the province had been “punished for fabricating and spreading rumors related to the pandemic.” Although punishments aren’t described, multiple international news outlets have reported accounts of internet police detentions that involve hours of interrogation, forced loyalty pledge signatures, and threats to family members and children.

Neither Chinese Cybersecurity Defense officials nor regional police responded to requests for comment.

Some public support

During the COVID-19 outbreak, some citizens of mainland China said they weren’t entirely opposed to the "rumor-busting" campaign.

“If you just follow whatever is online, you do not have the values to make your own judgments," said a Beijing homemaker who identified herself as Ms. Li, adding that she supported the new law because online commenters "behave like a herd."

"I think it is a sad thing,” she said.

Others said that while the censorship is often overly strict, the censoring of panic-inducing misinformation about the virus can be a necessity for those who rely on accurate reporting to help them navigate the crisis.

Western legal observers such as Jeremy Daum of China Law Translate have slammed the law as "distressingly vague and easily abused," arguing that it expands state authority to carry out questionable detentions like the December 2019 arrest of Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang.

Li, 34, was held for questioning after alerting a medical school alumni group on the Chinese messaging app WeChat to a mysterious SARS-like illness that proved to be COVID-19, which has since claimed the young doctor and more than 237,000 other people worldwide.

"In the future there will be only good news, and no bad news," wrote one Weibo user on March 1, using the hashtag “online news eco-system governance” to announce the law’s enactment.

According to The Guardian, that hashtag was reposted millions of times before being taken down the following day.

Weibo user Biyan (@碧言) seemed to suggest that the law wasn't a simple question of good or bad.

“I have the right to repeatedly tell myself to be calm about rumors and abuse,” he posted. “But you and I as individuals are under a big net that is gradually tightening.”

Yang Bin and Ziwen Jiang of VOA's Mandarin service contributed to this report.