Not too long ago, Un Neng dropped out of seventh grade in Kratie Province to join her parents working at a construction site in Sihanoukville, a sleepy coastal city now undergoing a casino building boom fueled by Chinese investors and encouraged by the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Most of the time, Un Neng, 16, carried baskets filled with lime mortar to the skilled workers at a condominium under construction. Up, up, up she went, past the third floor, past the fifth floor, and on to the top floor, the seventh.

For Un Neng and her parents, it was a work-for-home opportunity because in Preah Sihanouk Province the white-hot real estate market makes it impossible for workers to live anywhere outside the shells of buildings they’re hired to construct.

Partially completed building

On Friday, June 21, Un Neng ate dinner with her parents, Tep Ney and Prum Den, both 45 years old, then she fell asleep in a structure that was about 80% complete, even though no permit had been filed to allow construction to begin.

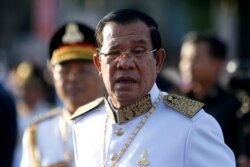

About 4:45 a.m. Saturday, just about a half-hour before dawn, the building collapsed. Later in the day, Hun Sen visited the site, and as allegations swirled about the building’s Chinese owner, he said, “Do not accuse this nation or that nation. … What matters is that we gather all investors into Cambodia” under Cambodian laws.

Increasingly those laws appear to be dictated by Hun Sen’s ruling party and bending to China.

As Hun Sen has cracked down on civil society organizations, the press and the opposition to create what is essentially a one-party state, Western donor nations have reduced or eliminated aid in a country where the per capita income was $1,563 in 2018, according to Cambodia’s finance ministry. Hun Sen has said China will fill the gap.

That process is visible in Sihanoukville, where a special economic zone represents Cambodia’s special relationship with China based on Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

China holds nearly half of Cambodia’s $7 billion in foreign debt, and it is one of Cambodia’s biggest trading partners, with bilateral trade reaching $5.6 billion last year.

Chinese investments are transforming Cambodia’s real estate market and gaming industry.

According to the provincial department of land management, it received 186 construction projects worth $582 million in the first five months of 2019, while the entire last year (2018) it received 336 projects worth about $1 billion.

Last week, Hun Sen established a special task force to inspect all buildings under construction in the province.

Since then, inspectors have tagged five unpermitted sites.

Preap Kol, director of Transparency International Cambodia, told Al Jazeera in Sihanoukville “hundreds of buildings have been constructed or are under construction (and) many of them were built without license or quality control. Bribes facilitate this.”

That “high level of corruption,” as the 2016 Cambodia Enterprise Survey by the World Bank puts it, a widespread “build first, permit later” attitude left many local people thinking it was only a matter of time before a building collapsed.

Then one did, killing 28 workers, including Un Neng’s parents. Other than her, the collapse injured 26 people.

‘Everything ... was pitch black’

Un Neng told VOA Khmer that when she “woke up … everything around me was pitch black.”

“I learned that [my parents] died instantly because I was sleeping next to them,” Un Neng said from her bed at the city’s central hospital last week. “I heard them shouting in one voice, then it turned completely silent, and their bodies were as cold as an ice cube when I touched them.”

For almost 24 hours, Un Neng waited next to the corpses of her parents.

“I could do nothing beside trying to push the concrete and rubble on top of my body, but it did not work,” she said as she recovered from bruises and numbness that came from being trapped for such a long time.

“I shouted for help, but the people outside could not hear me, while I could hear the rescuers working on the relief very clearly,” she said. “All I ate was a bottle of yoghurt drink that I bought the night before and placed near my bed.”

About 1,400 rescuers spent nearly 70 hours at the site, extracting the last two survivors around 4 p.m. June 24 — more than two days after the collapse — as monsoon rains poured.

‘Heard and felt the collapse’

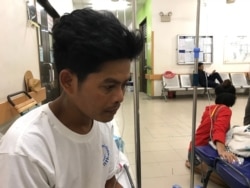

One of the two men rescued, Ros Sitha, now occupies a bed near Un Neng in the intensive care unit.

He heard and felt the collapse just after he checked his mobile phone, which was charging.

“I woke up soon before [the collapse] turning to my mobile phone, which was plugged for electricity charging, when I heard and felt the collapse,” Ros Sitha, 40, told VOA Khmer.

“It fell very, very quickly onto my body [so] that I had no time and chance to escape,” said Ros Sitha, who had been installing floor tiles for the previous two months. “I turned to my mobile phone to call for help, but it didn’t work.”

‘It was suffocating’

With his 18-year-old nephew, Kak Kea, Ros Sitha waited to be rescued. The stench of their colleagues’ rotting bodies filled the small space where they were trapped.

“It was suffocating and we felt our lives were on the brink,” said Kak Kea, who had started work at the site two days before the collapse.

“We tried to move our bodies and adjust our breath. … I lost all hope,” said Kak Kea, who dropped out of school in Prey Veng Province to work with his uncle. “If the rescue has taken several hours more, I would have died as I lost all my energy.”

Another survivor, Phat Sophal, 37, from Prey Veng Province, a poor rural area in the Mekong River lowlands, spent six hours trapped among piles of debris, praying and calling for help.

The rubble “became heavier and heavier as time went by,” the experienced construction worker told VOA Khmer. “I was very afraid of my life. I thought of my wife and my five children at home with no hope that I could get out alive as it was completely dark.”

Bruised and battered, Phat Sophal is now recovering.

Dismissed and promoted

During the relief operation, Hun Sen ordered the removal of Senior Minister Nhim Vanda, deputy president of the National Committee for Disaster Management for “irresponsibility” and “lying.” Yun Min, the province’s governor, resigned.

Quickly rehabilitated, Nhim Vanda now serves as a government adviser with a rank equal to that of a senior minister. Yun Min, a lieutenant general in the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, received a promotion after resigning and is now a four-star general serving as secretary of state of the Ministry of National Defense.

Five Chinese nationals, including the primary investor, a Vietnamese and a Cambodian steel worker were detained at the provincial court’s order on a variety of charges, including “unintentional murders.”

The Cambodian government’s anti-graft czar Om Yentieng claimed on June 28 that corruption was not a factor in the collapse.

The World Bank described in an August 2018 report that the real estate developments in Preah Sihanouk Province were “uncontrolled.”

“With no land use plan to guide development, the cityscape has changed dramatically, with new high-rise developments out of place in a traditionally low- to medium-rise urban environment,” the World Bank added.

Sok Kin, president of the Building and Wood Workers Trade Union Association, has questioned how authorities could overlook a seven-floor building without a permit.

“As an ordinary citizen, you would be stopped by the authorities if you built your house without their permit,” Sok Kin told VOA Khmer.

Un Neng, now orphaned, remains at the Preah Sihanouk provincial hospital. What does she plan to do when released?

“I’ll head home [in Kratie Province]. I don’t know what to do next.”