Earthquakes are a fact of life in Pacific Rim countries, but most are small shocks that don't do much damage. But a major quake - one registering more than 6.0 on the open-ended Richter scale - can devastate communities, even those that have prepared for disaster. In many urban centers around the Pacific Rim, it could be weeks or a month - or more - before water service gets restored after a major earthquake - not to mention electricity, sewage and fuel supplies too. So leaders on both sides of the Pacific are being forced to make cost-benefit choices.

Japan has a deserved reputation as one of the best prepared countries in the world for earthquakes. But even there, quakes can causes massive and lasting damage.

The magnitude 6.9 earthquake that struck Kobe in 1995 knocked out water and electricity, collapsed a main highway and railway and killed more than 6,000 people. Fires consumed entire neighborhood blocks as firefighters were stymied by the failure of the water supply

Kobe is now in the process of replacing nearly 4,800 kilometers of cast-iron water distribution lines with flexible pipe to make its system earthquake resistant.

Hitoshi Araike, an assistant manager at the city’s Waterworks Bureau, explained "The damage we have received in the earthquake kind of determined that we will do that, replace the pipes."

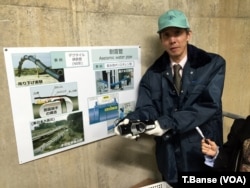

Araike and an interpreter led foreign journalists deep underground to see a new large transmission main that can double as emergency water storage. It cost more than $300 million.

Automatic shutoff valves have been installed at reservoirs to keep water from draining away after a quake. Flexible pipes and new-style connectors with reinforced sleeves resist breakage. They're being deployed at both the waterworks and a rebuilt sewage treatment plant, and once the new technology is in place, Araike expects “zero disruption” of Kobe’s water service after the next great earthquake.

Earthquake resilience elsewhere

Other Pacific Rim countries with memories of great earthquakes are investing in seismic strengthening, notably Chile, Taiwan, China and New Zealand. In any case, it takes a long time and a lot of money to make a difference, at a city or regional level. Lack of resources or building code enforcement can be a barrier in less developed countries such as Pakistan or Cambodia.

A big public utility on the U.S. West Coast also has an ambitious earthquake resilience goal.

"We'd like to get back up and be operating within three to four days,” says Jim Miller, engineering superintendent for Everett Public Works in western Washington state. “That's our goal from a level of service standpoint."

Miller says his utility assessed its earthquake vulnerability and has prioritized a list of improvements. First, contractors are reinforcing walls and ceilings to earthquake-proof the operations building at Everett's drinking water treatment plant, which serves 600,000 people north of Seattle.

Next, the Public Works Department wants to install flexible joints at some pipeline water crossings. Everett's full list of seismic upgrades could take 20 years - and many millions of dollars - to complete. City residents would have to cover that cost with higher water bills, but Miller says that the price of resilience.

"If we did nothing, that's more business as usual and you could keep rates lower. But we've found people for the most part expect a reliable system," he said. "Once they understand what it's for, they seem -- In fact our wholesale customers have actually encouraged us to make our system more resilient."

Other utilities in the region are taking similar steps. Seattle Public Utilities aims to finish a comprehensive vulnerability assessment of its own by the end of this year. It has already invested $60 million in seismic upgrades to existing water infrastructure to date - such as switching from above-ground to buried reservoirs.

In Oregon, a state resilience plan set a goal for water supply systems to be mostly operational within two weeks after a Cascadia mega-quake.

"We're nowhere close to that," admts Theresa Elliott, Portland Water Bureau chief engineer at a conference earlier this year.

Be prepared for a long wait

Earthquake resilience experts in both Pacific Coast states delivered nearly identical recommendations a few years ago. They said Oregon and Washington should require utilities to do vulnerability assessments and make plans to mitigate the deficiencies. But that remains largely a suggestion, not a requirement, and that could limit the effectiveness of efforts to increase resiliency.

A regional water supply group for the greater Seattle area recently estimated outage times for a big offshore earthquake and close-by shallow ones. Their analysis found it currently could take up to 60 days to restore service to most customers.

Those projections for long outages of vital services mean residents need to prepare to survive on their own. State and federal emergency managers used to recommend to stockpile food, water and medicines for three days. Now Oregon and Washington state suggest people in earthquake country prepare a kit with two weeks' worth of disaster supplies.