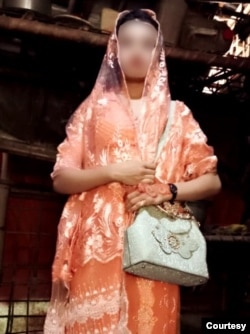

Dressed in an embroidered salmon-hued outfit and sparkling silver boots, a girl gazes seriously into the camera. She stands in stark contrast to the dingy background — walls and a roof fashioned out of crisscrossed bamboo sticks and plastic drape sheets.

The photograph is sent to a network of relatives and family friends who forward it to prospective grooms.

The Rohingya Muslim girl, Mubina Khatoon, was 13 on Dec. 2, 2022, when she boarded a Malaysia-bound boat in Bangladesh. Accompanying her were at least 32 more unmarried Rohingya girls and women from refugee camps in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Hamida Khatoon, Mubina's 20-year-old unmarried aunt, was also with her.

The boat, belonging to an illegal ferry service operated by human traffickers, has been missing since December 8, along with about 180 passengers aboard, all of them Rohingya Muslim refugees.

In a statement issued on December 25, the United Nations refugee agency, or UNHCR, described the boat as "unseaworthy" and said it had likely sunk at sea, killing everyone on board.

Since the release of the UNHCR statement, gloom has descended on the Rohingya refugee camp in Cox's Bazar. More than a million members of the stateless Muslim minority call the ramshackle, congested shanty colony their home.

Mubina's father, Shah Alam, 35, is a day wage laborer. He is one of the hundreds of refugees in the camp who had loved ones aboard the missing boat and are fearing the worst.

"Mubina is the oldest of my four children. I do not earn enough to arrange for a wedding celebration and other necessities for my daughter or sister, here in Bangladesh. So, we decided to send them to the Muslim-majority Malaysia," Alam told VOA in a telephone interview.

"My wife has not eaten in days and keeps weeping since we got the news of the boat drowning. … All of us feel lost and distraught," he said.

His tone brightened, however, when he spoke of his family's dreams about life in Malaysia.

"In the last 10 to 15 years, thousands of young men have traveled to Malaysia from Bangladesh and Myanmar and settled down there with good jobs. They want to marry Rohingya women. A distant cousin in Malaysia said he could easily find grooms for Mubina and Hamida.

"Our girls would be safe and happy there; the economic and living conditions of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are atrocious," Alam said.

The promised land

Several girls have succeeded over the last few years in achieving the Malaysian dream — one of an average life.

Surah Khatoon, whose husband died in Myanmar in 2016, lives in Cox's Bazar now. Her oldest daughter, Sanowara Begum, now 20, married a Rohingya man in Malaysia after her arrival there in January 2021.

"My son-in-law earns well as a construction worker. Sanowara is very happy with him and their son, who is 1 now. Although I miss her often, it consoles me to remember that she is leading a good life now," Khatoon said in a telephone interview. She hopes to send her other children to Malaysia, too.

Between 2012 and 2015, a majority of the 100,000 Rohingya who took boats to Malaysia were young men, according to Chris Lewa, director of the Arakan Project, which works to support the heavily persecuted Rohingya population and monitor the community's movements.

"These young men who arrived earlier have by now managed to reimburse their debts for their own journey and to save some money to get married," Lewa said in a telephone interview. So, the men often offer to forgo the customary dowry and pay part or all of the cost of the journey of a bride to join them, she explained.

Soyed Alam, 28, is one such young man who works in a Kuala Lumpur restaurant after having moved to Malaysia from Bangladesh in 2014.

Shyly, Alam said, "I wake up every day hoping to receive news of the arrival of a suitable Rohingya girl in Malaysia from Bangladesh, whom I can marry. … I am past the usual age of marriage by my community's standards. There is a dearth of Rohingya girls in Malaysia, and there are many other expectant men here like me."

Settling down in Malaysia is no simple task for Rohingya refugees, however.

Until recently, the Malaysian government had been issuing UNHCR refugee cards to the Rohingya refugees who came to the country. A UNHCR registered refugee can work freely anywhere. According to the U.N., about 57% of the 181,000 officially registered refugees in Malaysia are Rohingya.

But for the last few months, the UNHCR has not been registering the new Rohingya refugees entering Malaysia, leaving them to enter surreptitiously by way of Indonesia with the help of traffickers.

Most of the Rohingya who have reached Malaysia in the last few months are unregistered refugees under the threat of arrest. They live inconspicuously to avoid police, settling in forest plantations, agricultural lands and rural areas.

No woman's land — or sea

The threats of drowning, dehydration and starvation are not the only ones faced by the Rohingya girls and women undertaking the illegal sea journey. Travel to Malaysia from Bangladesh for the Rohingya involves both sea and land-and-sea routes. Gender-based violence — particularly incidents of sexual abuse on the way — are common.

Most Rohingya girls are vulnerable to sexual abuse because they travel without a guardian, Jaan Mohammed, a refugee in Cox's Bazar, told VOA by telephone.

"I am aware of many such incidents of abuse. But survivors rarely choose to speak about the abuse, fearing it would jeopardize their marriage prospects," Mohammed said.

"A female relative got married in Malaysia three months after her arrival there. But, only four months after the marriage, she delivered a child. It was later revealed that she had been raped by several men during her land-and-sea journey," he said.

Activist Lewa said that during the sea journey, Rohingya women and girls have been raped or sexually harassed on the boat by crew members but also sometimes by Rohingya smugglers aboard.

She described one such incident of abuse in 2020.

"In that case, some women who landed in Indonesia said that the smuggler on the boat had selected some good-looking girls among female passengers and offered them to the crew for the night," she said.

Even risks of death and sexual abuse are not deterring Rohingya families in Bangladesh from sending their daughters to Malaysia.

Rawshidullah, who like many Rohingya does not use a surname, saw his 16-year-old daughter, Umme Salima, off when she boarded the ill-fated Malaysia-bound boat on December 2.

"We took Salima's photograph before her departure and sent it to a cousin of hers who is married to a Rohingya man in Malaysia. She had promised to arrange for a groom for my daughter. It had been a big relief for our family," he said.

Echoing Rawshidullah's sentiments, Shah Alam accompanied his daughter to the boat to bid her farewell, knowing he might never see her again. The Rohingya have no legal travel documents and cannot return to Myanmar or Cox's Bazar once they leave for another country.

"I knew I would probably never see my daughter in person again," said Rawshidullah. "What I was not prepared for was for her to go missing."