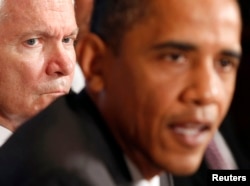

When President Obama took office six years ago, among the many burdens he inherited were two costly and complex wars: Iraq and Afghanistan.

He campaigned hard against the U.S. invasion of Iraq, calling it the “wrong war” and promised to bring home American combat troops, which took place in 2011.

The other war — Afghanistan — has posed a different set of dilemmas for the president.

Just this week, Obama was reminded of the grim realities of 13 years of military engagement when a man dressed as an Afghan soldier killed a two-star American general, the highest ranking officer killed in combat since 1970, according to the Pentagon.

The insider attack, claimed by the Taliban, has raised concerns about the hazards of the president’s exit plan — and the fragility of his Afghan policies.

Graeme Smith, a Kabul-based senior analyst with The International Crisis Group and a former journalist, said there is a clear trend that insurgents are making gains in remote parts of Afghanistan.

Case in point: Marjah, a district in southern Helmand province, long a Taliban stronghold, that was cleared in 2010 by NATO and Afghan troops.

“Insurgents are now operating within about eight kilometers from that district center [Marjah],”said Graeme, adding that violence is on the rise four years later.

“You can look at national level data and see quite clearly that more women and children are getting killed and injured this summer than at any period of time since 2001,” he said.

The situation on the ground has not deterred Obama from pursuing his endgame. In May, he said all American combat troops will leave at the end of this year. Nearly 10,000 others will stay on — but only until 2016.

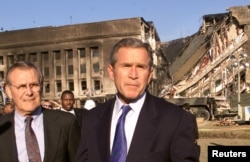

Bush and 9/11

It was the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington September 11, 2001 that got the United States in Afghanistan to start with.

Former president George W. Bush ordered an invasion to top topple the Taliban government and al-Qaida terrorists who were being given sanctuary – in particular, al-Qaida leader Osama Bin Laden.

The Taliban regime was toppled in about two months time, but bin Laden escaped capture, to be found and killed by American special operation forces under Obama’s command a decade later.

Bush continued his policy of counterterrorism military operations in Afghanistan, but soon turned his attention towards Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein as the number one national security threat against the United States.

Critics say that switch in focus was a key misstep — one that would inform the narrative of Obama’s policy when he took office in 2009.

“While we weren’t looking, al-Qaida has strengthened itself, it’s strengthened the Taliban, it’s strengthened all these local militant outfits,” said South Asia expert Shamila Chaudhary, who advised former secretary of state Hillary Clinton and the late diplomat Richard Holbrooke on Afghanistan and Pakistan during Obama’s first term.

The groupthink among Obama’s advisors was that Afghanistan had been left to fester and turn into a full-blown insurgency, said Chaudhary, now a Senior Advisor to the Dean at the School for Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University.

“Afghanistan at that time was the forgotten war,” she said. “And so we need to pump in more money, resources, people. There needs to be a military surge, but also a civilian surge.”

A new strategy was needed. It was announced just two months after Obama took office in 2009.

‘Af-Pak’ strategy

The overhaul of the Afghan war was dubbed Af-Pak.

The Pak referred to Pakistan, reflecting the idea that success in Afghanistan could not be achieved without a stable Pakistan. And that, went the thinking, would require a far deeper American engagement in Pakistan.

To implement the new strategy, Holbrooke was named the special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan (SRAP) , but the status of his portfolio was somewhat ambiguous.

While it was given an office in the State Department, SRAP was never part of any actual chain of command within the administration, a situation that experts would say undermined Holbrooke’s effectiveness.

Nonetheless, the legendary diplomat and his team of experts began their work with a sense of mission and of history making.

“One of things we recognized then…was that this is a ultimately a political issue within Afghanistan, right?” said Vikram Singh, a counterterrorism expert who was recruited to work for Holbrooke’s team.

Singh, currently the Vice President for National Security and International Policy at Center for American Progress, said that idea was the bottom line for their work.

“So, while we went in because of terrorism hitting us, Afghanistan’s future depends on some kind of durable political framework that can run that country and resolve disputes peacefully,” he said.

In addition to SRAP, Obama turned to senior military officials to get a clear picture of the situation on the ground. He asked then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to assess U.S. military needs and recommend how many more troops should be deployed.

According to experts involved in the new plan — one that turned Bush’s counterterrorism strategy into a counterinsurgency effort — Obama was primarily driven by his goal to end U.S. involvement there. And that singular focus, critics say, set up the entire process to fail.

The disillusionment eventually became public when Vali Nasr, a former senior advisor to Holbrooke and now the dean of SAIS at Johns Hopkins University, published his book The Dispensable Nation: American Foreign Policy in Retreat.

It was a blunt and scathing account of Nasr’s experience working for the Obama administration, in which he accused the president of forsaking American influence for political expediency.

It also accused White House staffers of undermining Holbrooke, and severely weakening American diplomacy.

For Stephen Biddle, a professor of political science at George Washington and an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, the president erred when he signed off on the deployment of an additional 30,000 troops to Afghanistan – and set a firm date for their withdrawal.

“There’s a certain arithmetic to counterinsurgency,” Biddle said, who was recruited to help American General Stanley McChrystal, then Commander of ISAF troops in Afghanistan, decide how many more U.S. soldiers would be needed to reverse what was widely seen then as a war America was losing.

“You can either conclude the war faster by sending more troops. Or send fewer troops, but let the war run longer,” Biddle said. “What you can’t do is conclude the war fast and not send very many troops and that’s what they decided they wanted to do.”

Obama chose to split the difference of what his military commanders pitched.

It was a painful process, according to Gates, who describes a deeply divided administration in his book Duty: A Memoir of a Secretary at War, published earlier this year.

Furthermore, a political settlement — believed by Holbrooke to be the key to securing America’s interests in Afghanistan and Pakistan — was nowhere in sight. And Holbrooke’s sudden death at the age of 69 in late 2010 brought the work to a screeching halt.

Legacy

Obama’s hesitance to engage in a longer, some would say more thorough, effort in Afghanistan is not atypical of how most modern presidents view foreign engagement, said Daniel Serwer, professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and scholar at the Middle East Institute.

“I think it is fair to say that all American presidents since the end of the Cold War have tried to avoid commitments abroad. Obama is not out of the ordinary in this respect,” Serwer said.

But what is unusual about this president is his discipline, he said.

“Obama really tries to stick to his schedule. He is unusually disciplined in not doing these things,” he said, adding that the president appears to have no qualms about pulling out and leaving places to “their fates.”

But there is wide concern that time is running out for U.S. moves in Afghanistan.

Biddle said the situation is made worse by the fact the war we now have in Afghanistan is a stalemate militarily.

And to simply maintain the status quo as U.S. troops drawdown, the Afghan National Security Forces will need continuous financial backing, the kind of which only the U.S. Congress can provide.

And that, said Biddle, will not continue indefinitely.

“If this is the state of affairs, then the war becomes a contest of stamina between the Taliban and the U.S. Congress,” he said. “And the Congress is not going to win that race.”

Further, not having a political deal in place as the clock winds down worries observers. Afghanistan is mired a protracted political fight over who will be its next president — a fight being mediated personally by Secretary of State John Kerry who is in Kabul yet again.

“Somehow or another you have to have a plan…for how you’re going to bring about negotiated settlement before the Congress defunds the war, the Afghan military collapses and we simply lose,” Biddle said. “And I think the administration has done a poor job of putting together a strategy for bringing about that settlement.”

Singh, who was front and center in the Af-Pak effort, frets about the future of Afghanistan.

“I feel good on one hand. And I feel very worried on the other hand,” he said.

The recent Afghan presidential elections are cause for hope he said, pointing out that the first round went far better than expected. The second round has been compromised by allegations of fraud and a yet to be resolved dispute between the top two candidates.

“What we have achieved offers a lot of potential,” Singh said. “But it’s extremely fraught, and it’s very fragile.”

For his part, the president seems intent on staying the course.

“We’re finishing the job we started” more than 12 years ago, Obama said in May, when he announced his latest timetable for withdrawing American troops from Afghanistan.