Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s popularity in Russia has reached an all-time high, according to a poll by the independent polling agency Levada Center, the results of which were published on April 16.

The survey was conducted among 1,638 Russians aged 18 years and older in 50 Russian regions. “In 2019, the aggregated rating of positive attitude (‘admiration’, ‘respect’ and ‘sympathy’) towards Stalin reached the maximum indicator in all years of research,” the Levada Center stated, emphasizing that the main indicator of the trend was the growth in “respect” for Stalin: it increased 12 percent since the last poll.

The dynamic of previous years demonstrates that beginning in 2015, the number of Russians expressing negative or neutral feelings towards Stalin started shrinking, while the negative/positive ratio was equally balanced earlier in the 2000s and “neutral” was dominant from 2008-2014.

Seventy percent of the respondents in the latest poll by the Levada Center said Stalin’s rule had been good for the country, and 46 percent said that the repression, mass killings and political persecution that accompanied Stalin’s 31-year rule until his death in 1953 were “definitely” or “in some way” justified by the results achieved.

Commenting on the results of the Levada Center’s survey, Sergey Chernyakhovsky, a political science professor at Moscow State University, said Stalin’s growing popularity was a sign of Russians’ thirst for “great goals” and “immediate great results.”

“The growing popularity of Josef Stalin is a request for success, changes and firmness. It is a request for great goals. People want to see great goals and great results in the shortest time,” Chernyakhovsky said, adding: “I do not want to sing hallelujahs to Stalin, but in the 1930s a new factory or new plant was launched every two minutes.”

Chernyakhovsky’s claim that “a new factory was launched every two minutes” appears to be overstatement and is self-evidently false. Stalin did push for rapid industrialization from the late 1920’s through the following decade.

Chernyakhovsky suggests that Stalin’s popularity developed organically in a Russian society hungry for success and a “firmer hand.” He does not address the question of whether the Russian state cultivates positive views of Stalin.

The idea that Russians are seeking a firm hand is a key element in the “national archetype” concept that is popular among both the Russian and Western thinkers.

However, other experts in Russia dispute whether such a “desire” is the main factor in Stalin’s growing popularity.

For instance, Valery Fyodorov, the director of the state polling agency VTsIOM (All-Russian Public Opinion Research Center), outlined other causes for the “ongoing mythologization” of Stalin.

“The most vulnerable part of preserving historical memory is that science and education are not the main sources of knowledge about the political repression. That, after decades of silencing repression, stimulates the growth of myths about Stalin,” Fyodorov said.

Ekaterina Shulman, an associate professor at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, said the information gaps provide an opportunity for the “rulers” to use the figure of Stalin in their own “power games.” Schulman added: “The ‘tops’ are loyal to the creeping re-Stalinization of the ‘bottoms’.”

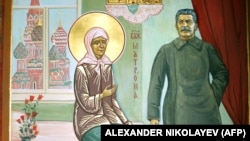

Manifestations of “creeping re-Stalinization,” as Shulman describes it, are evident across Russia -- from souvenirs to new monuments to pro-Stalin rallies. Stalin’s face can be seen on various items on display in internet or grocery stores and even in Orthodox churches.

Russian pop culture, specifically the film industry, helps explain why Stalin is becoming more popular. The cost, in human lives and suffering, of Stalin’s purges of Soviet society rarely appears in such films.

The victory over Nazi Germany in World War II is a major source of Russian national pride, and Stalin is omnipresent in the abundance of movies and TV series on “the Great Patriotic War” produced and delivered to the Russian people annually.

Out of the hundreds of films listed in the catalog, only handful tell the stories of victims of Stalin’s purges, while the absolute majority depict Stalin as an altruistic leader, a savior of the people, a wise and great leader outwitting and defeating all evil, and “father” of the Russian nation.

The production and release of films in Russia is controlled by a special commission of the Ministry of Culture (to which Chernyakhovsky has been a consultant since 2012), which approves or rejects proposals for films to be produced in Russia and issues distribution certificates for foreign movies. The ministry is also tasked to deliver “Goszakaz” -- government orders for art production and services.

Some of the Ministry of Culture’s decisions raise a question mark over its claim that there is no art censorship in Russia.

For instance, in January 2018 the ministry banned a political satire “The Death of Stalin,” labeling the movie “extremist material” and claiming it was part of a Western plot to destabilize Russia by “causing rifts in society.”

Last week, when the Hollywood action fantasy “Hellboy “was released in Russia, bloggers and media noted that the film’s Russian distributor, Megogo Distribution, replaced the name “Stalin” with “Hitler” in the Russian-language voiceover for the film’s narration.

In the original scene, the main character, Hellboy, meets with Baba Yaga – a popular witch character from Russian folklore. Baba Yaga tells Hellboy she once tried to resurrect Stalin so he would serve her evil plans. But in the Russian version, the witch refers to Hitler instead of Stalin. “Megogo Distribution” did not respond to Russian press queries about the reasons for this change.

Experts’ arguments and the actions of Russia’s Ministry of Culture suggest that Stalin’s positive image has been carefully protected and cultivated in Russia, while the historical truth about his atrocities remains a subject of scholarly literature and museum exhibits, narrowing the circle of people inside Russia who know this history.