The response by U.S. media to their earlier reporting on the so-called Steele dossier underscores the need for transparency to maintain credibility and the audience’s trust, analysts say.

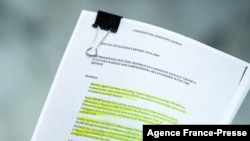

First published by the news website Buzzfeed, details from the dossier contained explosive allegations of conspiracy between then-presidential candidate Donald Trump and Russia, and it became a focus of heavy news coverage in the closing days of the 2016 presidential election.

But several of its damning claims were later found to be unsubstantiated and a federal indictment unsealed in early November revealed charges against the analyst, Igor Danchenko, who allegedly collected some parts of the dossier, for lying to the FBI.

Now, several U.S. news outlets have updated or corrected past reporting on the story.

The Washington Post, for example, removed and corrected sections from two articles published in 2017 and 2019, and removed a video that summarized an earlier article. A note on the 2017 article said that details have since been contradicted, including that Belarusian American businessman Sergei Millian was a source for the dossier.

Executive Editor Sally Buzbee was cited in a Post article about the changes as saying the paper “could no longer stand by the accuracy of those elements of the story.” Previously Millian had denied that he had helped Steele with the dossier.

CNN, in an article headlined: “The Steele Dossier: A Reckoning” said that subsequent lawsuits and investigations had “discredited many of [the dossier’s] central allegations,” and raised questions over the “political underpinnings of some key explosive claims.”

BuzzFeed, meanwhile, has stood by its original decision to publish the dossier. The article is still available online, along with a note at the top informing readers that, ‘the allegations are unverified, and the report contain errors.”

For Bill Grueskin, a professor at Columbia University’s journalism school, the discredited dossier is an example of the complexity journalists deal with when deciding whether to publish.

In mid-November, Grueskin published an essay in the opinion section of The New York Times, headlined: “How did so much of the American media get the dossier so wrong?”

One of the answers, the essay suggests, is Donald Trump's personality.

"Washington Post fact-checkers would eventually catalog more than 30,000 Trump falsehoods during his term in the White House,” Grueskin wrote. “When a well-known liar tells you that something is false, the instinct is to believe that it might well be true."

In an interview with VOA, Grueskin said that although there was evidence of Russian misconduct in 2016, “There are also many incidents when Trump's conduct toward Vladimir Putin showed tremendous obeisance.”

Because of that, Grueskin told VOA, "There was a tendency to believe the worst.”

The dossier’s most grandiose allegations have not held up over time. News reports now often refer to it as being “largely debunked.” But there are some well-known aspects that it did get right, including that Russia’s Vladimir Putin actively favored then-candidate Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton and there were multiple contacts between Russians and people in the Trump campaign.

U.S. intelligence agencies concluded that Russia interfered in the 2016 election. The FBI found evidence of a hacking and propaganda campaign, and at least three Russian companies and 25 individuals were later indicted, the Reuters news agency reported.

Lessons learned

Grueskin didn’t speculate on whether BuzzFeed should have published the dossier. But, from a broader perspective, Grueskin said, “If you can't verify something, you don't publish it.”

As a journalism professor, Grueskin said the advice he gives to students includes “being transparent with the audience about what a reporter knows or doesn’t know.”

“I think it's fine for a reporter to have a prominent paragraph on the top of the story that says, ‘This is what we don't know yet. These are things that we cannot confirm,’” he said.

For Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at the University of Minnesota’s Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, the important takeaway from the media’s reckoning over the dossier is the significance of correcting mistakes.

“Good quality news organizations are always prepared to correct their mistakes,” Kirtley told VOA. “Journalists publish millions of facts a year and the odds are that they're going to get some of them wrong. The issue is not whether you make a mistake, but whether you correct it.”

The lessons of good reporting are well known, Kirtley added.

"You need to be skeptical about sources in stories. If they seem too good to be true, they probably aren't,” Kirtley said. “You need to consider what the motives are of sources that give you the information. And you need to make an attempt to validate and verify the information by using more than one source for it."

VOA news articles and radio and TV broadcasts covered the news of the Steele dossier, its impact on American domestic politics and in U.S. relations with Russia. The coverage included Trump’s remarks on the Steele dossier along with later information about errors and concerns over the dossier’s sources.

“It's standard operating procedure to follow up a story when the original report has inaccuracies. It's any news organization's responsibility to its audience to be accurate and comprehensive in its reporting,” said VOA standards editor Steve Springer.

“Why is transparency of corrections important? Because of trust in the news organization and the reporter, the answer is plain and simple,” Springer added.

Correcting errors, maintaining trust

As American media outlets have revisited their coverage of the Steele dossier, the corrections have generated their own controversy as outlets accuse competitors of bias in their coverage.

Some of this is a byproduct of America’s increasingly polarized political culture. Media professor Kirtley said there is evidence that politically tilted coverage undermines the public’s trust.

“Most of the people are relying on the same sources over and over again. And if those sources have a particular viewpoint and don't have the ability to independently analyze information, then they're not going to be well served by that," Kirtley said.

"The public deserves independent journalism and independent reporting," Kirtley said.

Her belief is backed by data from the Reuters Institute of Journalism at the University of Oxford. Research released this year found that globally, “despite more options to read and watch partisan news, the majority of respondents (74%) say they still prefer news that reflects a range of views and lets them decide what to think."

A further 66% said news outlets should “try to be neutral on every issue.”

The impact of partisan media is reflected in audience trust, which in the U.S. has fallen to 29% -- the lowest of all the countries included in the research.

Craig Allen is an associate professor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

According to Allen, the growing distrust in the media is a long-standing trend. Part of the problem is competition at a time when newsrooms have fewer resources, Allen said.

"As a result, they don't fact check; there aren't resources available to check into information,” Allen said. “It's easier just to report what you think or what you feel rather than what was proven."

According to an October Gallup poll, cited by Allen, an estimated 7% of Americans have "a great deal" and 29% "a fair amount" of trust and confidence in newspapers, television and radio news reporting.

The poll indicated “68% of Democrats, 31% of independents and 11% of Republicans trust media.”

This story originated in VOA’s Russian Service.