WASHINGTON —

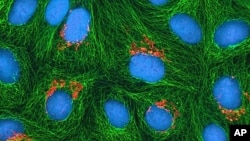

Scientists have successfully crippled aggressive cancer cells by disabling a single protein known as an ether lipid, part of a family of fatty molecules that includes cholesterol. Researchers hope to develop drugs that can be used alongside chemotherapy to treat some malignant cancers.

Ether lipids are highly elevated in aggressive cancer cells, and by disabling the enzyme responsible for their production researchers have been able to disable malignant cancer cells.

Ether lipids are normally found in cell membranes. So it makes sense that their levels are high in aggressive tumors, because tumors need the nourishing fatty molecule to divide and grow at an accelerated rate.

Researchers at the University of California Berkeley, led by Daniel Nomura, converted skin cells into aggressive tumor cells in culture and then disabled an enzyme, called AGPS, that’s critical to the formation of ether lipids. They also injected mice with both cancerous skin cells and aggressive breast cancer cells, and the rodents quickly developed tumors.

But disabling AGPS, Nomura said, hindered the ability of the cancer cells to grow and spread. "They could still proliferate at least in culture. But at least in tumor models in mice, we could completely suppress growth,” he said.

Nomura said cancer researchers have known since the early 1950s that ether lipids play a role in cancer growth, but this is the first time scientists have shown how the fatty molecule facilitates cancer proliferation. He says ether lipids also exist in lower levels in benign tumors, and Nomura hopes blocking AGPS will prevent those tumors from becoming malignant.

Researchers are now trying to develop a drug that targets AGPS, increasing the chances that chemotherapy will cure many hard to treat cancers.

“Certainly I don’t think the AGPS inhibitor is the cure for every cancer, but it would probably be combined with other chemotherapeutic agents.”

An article on the role of ether lipids as a driver of aggressive cancers is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Ether lipids are highly elevated in aggressive cancer cells, and by disabling the enzyme responsible for their production researchers have been able to disable malignant cancer cells.

Ether lipids are normally found in cell membranes. So it makes sense that their levels are high in aggressive tumors, because tumors need the nourishing fatty molecule to divide and grow at an accelerated rate.

Researchers at the University of California Berkeley, led by Daniel Nomura, converted skin cells into aggressive tumor cells in culture and then disabled an enzyme, called AGPS, that’s critical to the formation of ether lipids. They also injected mice with both cancerous skin cells and aggressive breast cancer cells, and the rodents quickly developed tumors.

But disabling AGPS, Nomura said, hindered the ability of the cancer cells to grow and spread. "They could still proliferate at least in culture. But at least in tumor models in mice, we could completely suppress growth,” he said.

Nomura said cancer researchers have known since the early 1950s that ether lipids play a role in cancer growth, but this is the first time scientists have shown how the fatty molecule facilitates cancer proliferation. He says ether lipids also exist in lower levels in benign tumors, and Nomura hopes blocking AGPS will prevent those tumors from becoming malignant.

Researchers are now trying to develop a drug that targets AGPS, increasing the chances that chemotherapy will cure many hard to treat cancers.

“Certainly I don’t think the AGPS inhibitor is the cure for every cancer, but it would probably be combined with other chemotherapeutic agents.”

An article on the role of ether lipids as a driver of aggressive cancers is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.