It is hard to imagine what our planet was like 250 million years ago.

It had already suffered through the Permian Extinction, which destroyed most of our complex ecosystems and almost 95 percent of all life on land and sea.

A few million years later, in the very early parts of the Triassic Period, the planet did it again, inflicting another extinction event known as Smithian-Spathian.

This time, climbing temperatures did the damage.

Evidence suggests Earth heated up to its highest temperatures since its youth as a giant molten ball in space.

Average temperatures ranged from 50 to 60 degrees Celsius on land to 40 degrees Celsius in the world's oceans.

The result was a giant dead zone that stretched thousands of kilometers north and south from the equator.

The only animals to survive were the ones that managed to migrate to the cooler climates in the North or South.

Adapting to a rapidly changing world

Ichthyosaurs were one of the lucky few sea creatures that managed to live through both events.

After the first extinction, they and other huge marine predators, like plesiosaurs and pliosaurs, moved into the early Triassic-era waters 252 million years ago.

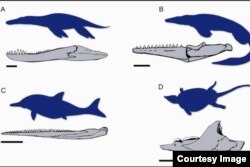

And new research published earlier this month in the journal Paleobiology by paleontologists at the University of Bristol suggests ichthyosaurs evolved rapidly to take advantage of the new types of prey in the waters.

"The range of feeding-related morphological adaptations seen in Triassic marine reptiles was never exceeded later in the Mesozoic," lead author Tom Stubbs said.

After the second great extinction, however, there is new evidence ichthyosaur evolution again kicked into high gear.

Big changes, big adaptations

Scientists from universities in China and the United States, along with a number of international museums, just released a new fossil that offers some tantalizing evidence as to their adaptability.

The research is published in Monday's Scientific Reports and centers on the discovery of an ichthyosaur called Sclerocormus parviceps that was completely different than the Loch Ness-looking dinosaurs we usually think of.

Sclerocormus had a short snout instead of the crocodile-looking set of teeth on most ichthyosaurs.

And instead of a tail with fins like a fish, this reptile had a long whip-like tail.

Its oddest feature perhaps was its toothless mouth and short snout that scientists think Sclerocormus used like a syringe to suck food off the ocean floor.

Researcher and author Olivier Rieppel from the Field Museum in Chicago told VOA he believes these dinosaurs came on the scene quickly. Rieppel said he sees "their evolution proceeding rapidly in the early to mid-Spathian" era.

Rieppel says the find is important because it suggests there was a lot more diversity in the waters of the Spathian era than previously thought.

It also adds to our understanding of how evolution works. "Darwin's model of evolution consists of small, gradual changes over a long period of time, and that's not quite what we're seeing here, Rieppel says. "These ichthyosauriforms seem to have evolved very quickly, in short bursts of lots of change, in leaps and bounds."

Life as it has been famously said, finds a way.