A man in faded blue overalls walks across a charred field, his black boots crushing dead leaves. Giant electricity pylons buzz overhead. Plumes of thick black smoke rise skyward in the distance.

"It’s the copper cable thieves again; they’re burning the plastic off the cables so they can get the copper," says the man.

A cold wind stirs red dust, and flaps the wrinkled cover of a discarded magazine, on which a sun-bleached Kim Kardashian pouts suggestively.

Over the years, Thanjani Mangoma has dug many graves here at the cemetery in Diepsloot, a huge, impoverished township north of Johannesburg.

But he says "it’s only the small graves" that affect him.

"I feel bad having to bury babies and children every week. Knowing they’ve been murdered very brutally, before they’ve had a chance to really live… that breaks my heart. All I can do is give them proper burials,” says Mangoma, wringing his large, calloused hands.

In the 20 years that Glenys van Halter has been establishing community projects in Diepsloot, "countless" children have been murdered, she says.

"They abduct them, they rape them and then they kill them so that they can’t talk," explains the elderly woman, who’s also a trauma counselor.

Toddlers’ bodies hidden in toilet

South Africa has among the highest rates of child and infant rape in the world. The country’s Medical Research Council says at least half of all children in South Africa will be abused before the age of 18.

Murder rates of youngsters are also some of the highest globally.

Diepsloot is one of the flashpoints. Van Halter remembers when two toddler girls went missing from their shack a few months ago.

She holds a photo of their bloated bodies, limbs twisted. One lies face down in filth next to a lavatory. The other corpse hangs inside the toilet, stuffed there by the killer.

"We found them stabbed and raped – one was 2 ½ and one was 4 – in this toilet, lying there in a heap. It took two days to find the mother, who was in a pub.… She was so dysfunctional herself that she wasn’t even aware that her children were in danger," says van Halter.

Small hands tied with wire

Van Halter says it’s easy to abduct and kill children in Diepsloot, because the township is a "place of chaos."

Hundreds of thousands of people live on top of one another in shacks. New people constantly stream in from all over the country and the continent. They come here looking for job opportunities as Johannesburg expands northward. Building sites are everywhere.

Community leader Brown Lekekela, who also manages the township’s only shelter for abused women and children, says parents here must often leave their kids alone to go into the city to scavenge for work.

"That means the young ones are easy targets for criminals," he says.

Also a counselor, Lekekela deals with a lot of child murders. He’s particularly affected by the rape and killing of three little girls earlier this year.

"That’s the worst, because they are innocent girls – 3, 4 years, a 2-year-old," he recalls, saying a 35-year-old man raped the girls. "And after that, he killed them, he strangled them! He put the plastic on top of their heads to suffocate them. I can imagine how much hurt or pain they went through when he was penetrating through those girls."

Lekekela pauses. His eyes flash. His face twists into anger and disgust.

"I’ll never forget their small hands, tied together with wire, before that man raped them one by one."

Tears fill his eyes. His voice shakes. He asks: "When they were crying, what was he doing? When they were bleeding, what was he doing, what was he thinking? And after he has done that, was it not enough, that he can put the plastic on top of their face, so that they can suffocate?"

Abuse of the disabled

Inside the house where the murdered girls were last seen, the walls are bare.

One of their mothers shifts on a tattered couch, and says she doesn’t know why she carries on with life, because she’s "empty, empty.…"

She seethes: "I don’t understand why did the guy take the kids and kill them like this. I don’t understand."

Local police acknowledge they haven’t got the resources to protect Diepsloot’s children. There are only a few specialist child protection officers here. They’re inundated with work.

On another stony street, boys shout as they play soccer. For goals, they use two lampposts pasted with posters advertising the services of a "Dr. Dakwa – herbalist specializing to bring back long-lost lover."

Not far from here, a few months ago, a mentally disabled 8-year-old boy says an older child forced him into a "painful" sex act, and then paid him 20 cents.

His mother says she knows his attacker, who lives nearby. But, as with most cases of such abuse in Diepsloot, her son’s alleged attacker hasn’t been arrested by the police.

Another mother trudges home with her baby on her back, after a hard day’s work washing clothes in a laundry.

She, too, knows the teenager who raped her 5-year-old son.

"I am very angry that this boy hasn’t been arrested," she spits. "Now he is free to abuse other children, and maybe even my son again. Who knows how many other kids he’s abused? There’s no justice here in Diepsloot."

Sex slavery

Lekekela says many men in Diepsloot see women and children as "commodities to be exploited."

He’s currently counseling a 14-year-old girl who was held captive by some men, who forced her to drink alcohol and take drugs.

"Then they locked her in a room for three days, whereby these guys, the main guys who were operating that brothel… they have been having sex with her every day, every day, every day, just for her to get used to what they are doing there," says Lekekela.

He adds that after days of constant abuse, the men told the girl, "It’s time for you to go to market."

For about a month, until she managed to escape, the girl was forced to have sex with about 40 men a day, Lekekela says.

Extreme poverty the ‘root cause’

Van Halter says it’s often men with "a bit of money" in Diepsloot who abuse women and children.

"It’s easy, they’re easy meat. They’re vulnerable. They’re sitting in a shack with no food. He can go and say to her, ‘Listen, I’m going to give you 10 rand, go buy some food for your kids.’ She’ll go to buy the food and he’ll rape the child while she’s away. Because he can. He doesn’t think it’s a big problem."

Van Halter is convinced that extreme poverty is the "root cause" of much of the harm being inflicted on the township’s youngsters.

"The youngest child I’ve rescued [from sex work] in Diepsloot was 3 years old. She was being prostituted to pedophiles by her own mother," Van Halter says.

"They were living in a cardboard box. And [the mother] said, ‘I’ve got four children to feed and I’ve got to sacrifice one… The only way I can save my entire family is to prostitute one child to these men, for 150 bucks [per sex act]. Then I can feed my children.'"

‘Don’t jail my father’

Van Halter says poor children often rely on their abusers for food and shelter. As such, it can’t be expected of a girl whose father is raping her, for example, to press criminal charges against the only person providing for her.

"Often, she’ll say, ‘But it’s my dad. I can’t do that to my dad. Just leave him alone.'"

And so, says van Halter, the cycle of abuse continues.

Local police say they don’t investigate most child rapes, because the victims almost always withdraw their allegations.

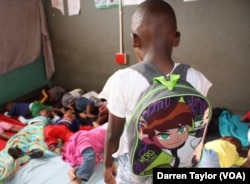

At a local crèche or child care center, a boy sings the national anthem for his teacher.

In his cartoon T-shirt, he looks like most of his 6-year-old classmates. But he, too, was raped recently. He, too, is just another casualty of a community seemingly at war with its children.

Darren Taylor is a reporter for VOA’s English to Africa service.