All About America explores American culture, politics, trends, history, ideals and places of interest.

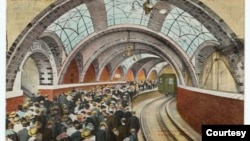

Buried deep beneath New York’s busy streets lies a secret gem, one of the city’s first underground subway stations. With its brass chandeliers, skylights and vaulted tiled ceiling, the Old City Hall Station makes New York’s modern depots look like poor distant relatives.

“I was blown away,” says Polly Desjarlais, the New York Transit Museum's content manager, of her reaction when she first saw the old station. “I think it's this perfect sort of time capsule. It's really this lovely, elegant and really unique space.”

New York’s first underground subway, which included the Old City Hall station, opened in 1904. Before then, New Yorkers used elevated trains and streetcars for public transportation. The Old City Hall Station, designed by prominent architects George Heins and Christopher LaFarge, with vaulted, tiled ceilings by master artisan Rafael Guastavino, was considered a “jewel in the crown” when it opened.

“It was a statement that New York City had arrived at the level of the great European metropolises like London and Paris, Rome, Madrid … that New York City was taking its place as a world city,” says Clifton Hood, a history professor at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York.

The Old City Hall Station was built during a period when many public buildings and spaces, such as Grand Central Terminal and the New York Public Library, were designed in a majestic way to show that New York could compete culturally with great European cities.

Built by railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1871, Grand Central is a commuter rail station with a vaulted ceiling featuring elaborate depictions of the sky and stars. The New York Public Library, dedicated in 1911 and funded by some of America’s richest men at the time, is a majestic landmark known for the twin lion statues guarding its entrance.

“[The structures] could have been pedestrian but are really pretty fabulous public buildings. They’re monuments, and the builders of the subways wanted something that would evoke the same kind of spirit,” says Hood, who is also the author of “722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York.”

“They wanted one station that would be especially magnificent,” he says.

Like Grand Central and the New York Public Library, the design of the Old City Hall Station was influenced by the French Beaux-Arts style, which incorporated neoclassicism, Renaissance and Baroque elements, while also using more modern materials such as iron and glass.

“There are gorgeous glass bricks that are flush with the streets that allow the daylight to shine through those leaded glass skylights,” Desjarlais says. “I've heard [the station] be described as a celebration of curves, because there are a lot of curves. Everything is sort-of rounded.”

But those graceful curves are what led to the station’s demise as a fully functional part of the underground transit system, because its rounded platform couldn’t accommodate longer trains.

“The platform at City Hall is really curved. It's a very, very tight curve, and the platform itself is just over 200 feet long. So, it's short,” Desjarlais says. “As the subway got busier … trains got longer, and we added cars. … We were growing those platforms and making them longer to accommodate longer trains. At City Hall, that curve made it virtually impossible to extend.”

The station was decommissioned in 1945, but it is still a functioning space. One train line, the No. 6, uses the Old City Hall Station to turn around. And while there is no public access to the station from the street, the New York Transit Museum offers paidtours to its members a few times a year.

“Limited access also helps us preserve as much as we can. And, I think, it makes it really special,” Desjarlais says. “It keeps that mystery, that lovely idea that just below our feet, we are possibly walking above this wonderful pocket of turn-of-the-century beauty and elegance.”

Today’s subway stations appear to focus more on function than looks, which historian Hood regrets.

“What is lost is a sense of possibility and aspiration, and really, exhilaration, too,” Hood says. “What the City Hall Subway Station really shouts is joy, exuberance. … It summons us to do more, and I think it lifts our spirits on a daily basis. These builders could have built a pedestrian station, but they didn’t. They had higher ambitions, and maybe we should think in those terms, too.”

Over the years, there was talk of turning the old station into a restaurant or tourist destination. However, after the 9/11 terror attacks, security concerns put those ideas to rest. Today, the unofficial way for the general public to catch a glimpse of the grand old station is by taking the No. 6 train and staying on after the last stop at the Brooklyn Bridge. When the train makes a U-turn at the Old City Hall Station, riders will be treated to a brief trip back to a more glamorous time.