In the remote forests of Africa’s oldest wildlife park, and at the heart of a civil war that has decimated the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s eastern region, the rangers of Virunga National Park are waging their own battle. They’re fighting to save the surviving families of mountain gorillas and 200 other endangered species, as well as the forests and savannahs of this U.N. World Heritage site.

Their formidable enemies include rebel units of the anti-government M23, a force comprised mostly of ethnic Tutsis, and several other militias, including the infamous Joseph Kony’s Lords’ Resistance Army from Uganda.

The Virunga rangers also combat poachers, who kill the gorillas to sell their heads and limbs on the black market, and a small industry of park trespassers who produce illegal charcoal.

The park’s warden, Emmanuel de Merode, estimates the rebels earn up to $35 million a year in charoal sales to support their wars. He also suspects the illegal charcoal manufacturers are responsible for the deaths of some gorillas because the animals are a “hindrance” to the illegal industry.

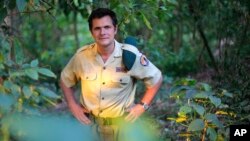

De Merode took charge of the park’s security – and later its regional economic development – through an agreement between Kinshasa and the African Conservation Fund in London. He is a descendant of Belgium’s King Albert I, who established the park more than 80 years ago to save the gorillas that have since gained world renown.

Challenges for Africa's oldest wildlife park

Today, as de Merode looks across Virunga’s eastern boundary at Rwanda, he sees a nation recently plagued with massive genocide but now reporting tourism revenues of $281 million because of the world’s fascination with gorillas.

Virunga, however, is directly in the path of 15 years of a civil war in which an estimated 5.4 million people in the DRC have died. Officials claim 90 percent of the fatalities – half of them children – have died not in warfare but as a byproduct of the war: cholera, malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia and malnutrition.

Since the park has been closed to tourists for more than a year due to the armed violence, the goal of building a tourism industry around the park’s wildlife is uncertain as de Merode defends the park and tries to build the regional economy.

The park maintains a corps of about 300 well-armed and highly trained park rangers. They patrol more than 7,800 square kilometers of near-pristine African environment: brilliant white glacial fields atop the Ruwenzori Mountains in the park’s north, the deep red flows of Nyiragongo’s volcanic lava in the park’s south, the gorillas in the Mikeno Mountain foothills, a few hundred hippos on Lake Albert and its marshes, and more than other 200 endangered species in between. In their battle to secure the park’s environment, more than 130 rangers have been killed.

In addition to the flora and the fauna, the rangers are also defending such park-sponsored developments as new roads, a small hydroelectric project, nine schools, a health clinic and a better way to make charcoal briquettes – a vital commodity for the region’s 4 million rural population.

Building a better briquette

Virguna’s economic planners came up with two kinds of charcoal. In the park’s innovative manufacturing site, local workers produce “the fireball”, a safer, more efficient charcoal-like briquette in a compressed form for local consumers. The fireball is a combination of cassava paste and charcoal dust recycled from the vast and less efficient charcoal-making companies of Goma, compressed into the shape of a golf ball and sold.

Village women in the region – many of them victims of rape by rebels as they searched for firewood in the forests - are employed in hand-pressing donut-shaped briquettes using locally appropriate technology prescribed by a development lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kim Chaix, a New York fundraiser and charcoal advocate who works with park administration on several development projects said armed rebels are now close to the charcoal manufacturing site.

The charcoal briquette-making project continues for now, but the goal of a thriving tourism industry and the survival of the mountain gorillas remains uncertain.

Even while the park is closed to tourists, Chaix and de Merode plan to attract more investment for the production of palm oil, papaya enzymes and soap, and commercial crops of indigenous bamboo for their briquette-making enterprise.

“We’re trying to create peace and economic security for four million people who live within a day’s walk of the park,” Chaix said.

Their formidable enemies include rebel units of the anti-government M23, a force comprised mostly of ethnic Tutsis, and several other militias, including the infamous Joseph Kony’s Lords’ Resistance Army from Uganda.

The Virunga rangers also combat poachers, who kill the gorillas to sell their heads and limbs on the black market, and a small industry of park trespassers who produce illegal charcoal.

The park’s warden, Emmanuel de Merode, estimates the rebels earn up to $35 million a year in charoal sales to support their wars. He also suspects the illegal charcoal manufacturers are responsible for the deaths of some gorillas because the animals are a “hindrance” to the illegal industry.

De Merode took charge of the park’s security – and later its regional economic development – through an agreement between Kinshasa and the African Conservation Fund in London. He is a descendant of Belgium’s King Albert I, who established the park more than 80 years ago to save the gorillas that have since gained world renown.

Challenges for Africa's oldest wildlife park

Today, as de Merode looks across Virunga’s eastern boundary at Rwanda, he sees a nation recently plagued with massive genocide but now reporting tourism revenues of $281 million because of the world’s fascination with gorillas.

Virunga, however, is directly in the path of 15 years of a civil war in which an estimated 5.4 million people in the DRC have died. Officials claim 90 percent of the fatalities – half of them children – have died not in warfare but as a byproduct of the war: cholera, malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia and malnutrition.

Since the park has been closed to tourists for more than a year due to the armed violence, the goal of building a tourism industry around the park’s wildlife is uncertain as de Merode defends the park and tries to build the regional economy.

The park maintains a corps of about 300 well-armed and highly trained park rangers. They patrol more than 7,800 square kilometers of near-pristine African environment: brilliant white glacial fields atop the Ruwenzori Mountains in the park’s north, the deep red flows of Nyiragongo’s volcanic lava in the park’s south, the gorillas in the Mikeno Mountain foothills, a few hundred hippos on Lake Albert and its marshes, and more than other 200 endangered species in between. In their battle to secure the park’s environment, more than 130 rangers have been killed.

In addition to the flora and the fauna, the rangers are also defending such park-sponsored developments as new roads, a small hydroelectric project, nine schools, a health clinic and a better way to make charcoal briquettes – a vital commodity for the region’s 4 million rural population.

Building a better briquette

Virguna’s economic planners came up with two kinds of charcoal. In the park’s innovative manufacturing site, local workers produce “the fireball”, a safer, more efficient charcoal-like briquette in a compressed form for local consumers. The fireball is a combination of cassava paste and charcoal dust recycled from the vast and less efficient charcoal-making companies of Goma, compressed into the shape of a golf ball and sold.

Village women in the region – many of them victims of rape by rebels as they searched for firewood in the forests - are employed in hand-pressing donut-shaped briquettes using locally appropriate technology prescribed by a development lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kim Chaix, a New York fundraiser and charcoal advocate who works with park administration on several development projects said armed rebels are now close to the charcoal manufacturing site.

The charcoal briquette-making project continues for now, but the goal of a thriving tourism industry and the survival of the mountain gorillas remains uncertain.

Even while the park is closed to tourists, Chaix and de Merode plan to attract more investment for the production of palm oil, papaya enzymes and soap, and commercial crops of indigenous bamboo for their briquette-making enterprise.

“We’re trying to create peace and economic security for four million people who live within a day’s walk of the park,” Chaix said.