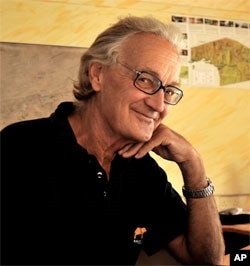

A man who’s devoted his life to saving Africa’s elephants is the winner of this year’s Indianapolis Prize. Iain Douglas-Hamilton receives $100,000 for “outstanding achievement in animal conservation.”

The award announced Thursday will be formally presented in September 25th in the Midwestern U.S. city of Indianapolis, Indiana.

Douglas-Hamilton is the founder and director of the organization Save the Elephants. His conservation efforts include rescuing desert elephants in Kenya and Mali during a severe drought, as well as working to end the illegal elephant ivory trade. He’s pioneered work in using GPS (Global Positioning System) to track elephant herds day and night not only in Africa, but Asia as well.

Upon hearing the news of winning the Indianapolis Prize, Douglas-Hamilton’s reaction was one of “surprise and delight.”

Money well spent

The conservationist says the monetary award will give him “a chance to do some things I might not have been able to do otherwise. Particularly to recognize some of the people who have been working for me long and loyally, who are sort of unsung heroes in conservation that I personally know about. And I know about their desperate needs.”

He adds, “It’s very rare to have a chance to actually have a sum of money at one’s disposal that one can use in an unrestricted way. Doing this, I think, will increase their pride in the job they do, which is conservation.”

Animals, people, space

A big conservation issue is the co-existence of people and animals.

“It’s largely a matter of space, of desperate human problems that spill over into animal problems. There is an expanding population that is living hand-to-mouth. And in actual fact is often degrading the habitat, moving into animal range. So there has to be a compromise. There has to be room for animals and room for people,’ he says.

That, he says, can only happen with good planning and good governance.

“I think our challenge is to provide the information as scientists. So, it’s going to help the planners. And actually to get one’s hands dirty with everything from top to bottom, including direct protection, helping with law enforcement and education – education is incredibly important,” he says.

The success of future conservation efforts may depend on younger generations being aware of the current problems.

“The future generations have the future of the animals in their hands. And how they feel about animals is going to be all important,” he says.

Worst case scenario, he says, is that education efforts fail and conservation programs are unable to protect some animals or species from going extinct. But Douglas-Hamilton is hopeful.

“I don’t think that’s going to happen so much. Not so long as there’s a growing body of international and home grown conservationists working together. If we all work together, nothing’s impossible,” he says.

Smart planning

The Save the Elephants director says it’s necessary to be “smart” about seeking a compromise between what’s best for animals and people and “not letting things develop in a haphazard way.”

He says, “For example, elephants have safe havens that are linked by narrow corridors. It’s really important to keep those corridors open, which can be done at relatively low cost if you know where they are.”

That’s where GPS technology comes in. “With our high tech radio tracking devices, we actually can precisely follow the elephants in real time day and night, in season, out of season, through forests, up and down mountains. And this kind of very precise information…is making the work of conservation a lot more accurate and focused,” he says.

Conservation takes on new urgency with the problems caused by climate change and its effects on both animals and people.

There’s just something about elephants

Asked why he’s devoted his life to saving elephants, he says, “Oh, it becomes a way of life. You leave university. You get your first job. And if it happens to be an elephant, you’ve become entangled in elephant life for the rest of your life. Very fascinating animals.”

Douglas-Hamilton says he’s never been bored working to protect elephants, adding people may not realize what sentient creatures they are.

He describes them as “intelligent creatures with quite complex feelings, emotions, relationships with each other and potentially relationships with individual human beings, too.”

He looks upon them as “one of nature’s great masterpieces. Just as the Mona Lisa is important to us as a work of art, elephants are a work of nature. And it would be vandalism to destroy something that was so perfect in its own way.”

Douglas-Hamilton currently lives and works in Nairobi, Kenya.