The HIV/AIDS epidemic is 30 years old. Nearly 30 million people have died from complications of the disease and more than 33 million are currently living with it. There’s a better chance than ever of living a long, productive life despite infection. But there’s still no cure or vaccine. The top U.S. official on HIV/AIDS talked recently about the early days of the epidemic and the progress that’s been made since then.

On June 5, 1981, the first official cases of HIV/AIDS were reported in the United States among gay men in Los Angeles. The disease was around long before that. It’s just that no one knew what it was or what to call it. It was already taking a toll in Africa, where it was called slim disease. That’s because people lost so much weight before they died.

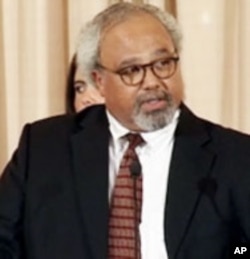

Ambassador Eric Goosby is the U.S. Global AIDS coordinator and is in charge of PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. But it wasn’t always so. In the beginning of the epidemic, Dr. Goosby worked in San Francisco, where a lot of gay men started showing up in the emergency room.

“I wanted to treat diseases that I could cure. Not chronic, progressive diseases, but diseases I could throw an antiretroviral drug at it or an antibiotic and end it. And the first group of physicians and nurses that cared for populations who were HIV impacted was mostly infectious-disease-oriented mindsets that came at it, not kind of oncology, hospice, chronic progress disease types,” he said.

He had 500 HIV/AIDS patients during his years in San Francisco. All 500 died.

“During a period of no effective antiretroviral therapy, we got very good at diagnosing and treating opportunities infections early. One infection, two infections, usually three or four infections and then the fourth or fifth one would take the patient,” he said.

Nothing worked

Goosby asked, “Was this a failure in my ability to be a physician? Was I failing the patient and the family that went through the death with the patient that I was caring for?”

When he met his patients, he knew he would be with them until they died. After seven years of this, it took a toll on Goosby and his colleagues.

“We all began to have more emotional liability than any of us had ever had before. I can remember seeing a stray dog on the street would upset me in a way that was disproportionate to what it should be. At the time there was a commercial about just phone home and that would well me up in an emotional kind of moment. And everybody who was in the clinic at the time had exactly the same thing. And it was really a post traumatic stress phenomena that we didn’t recognize at the time,” he said.

He and his colleagues began to gather and talk about their patients - and not just in a clinical way.

“You don’t get attached to every patient in the same way. But every once in a while you have a patient that for whatever reason you relate to on multiple levels and you grieve their loss. And acknowledging that we could do that and talk to each other about it, knowing all of us were in front of the same dilemma, made a huge difference for us,” he said.

Goosby says when he had his first son the realization of what was happening became most acute. Every one of his patients was somebody’s son and they all had parents who loved them as much as he loved his.

Africa

In the following years, Goosby played a major role in developing U.S. domestic HIV/AIDS policy. And then, in the early 90s, he visited Zambia, South Africa and Kenya.

“When I came to these countries, there were three, four people in the bed. There were people under the bed. People in the hallways. You stepped over people to get to patients on the ward. That was the norm in every hospital I visited and had mostly opportunistic infections that were TB related or cryptococcal meningitis toxoplasmosis,” said Goosby.

That’s a brain infection caused by a fungus. All the patients were in the late stages of HIV/AIDS. None had received antiretrovirals.

A lot has changed since then, not only due to scientific research and greater awareness, but also because of outspoken activism around the continent, including lawsuits demanding access to new AIDS drugs.

The PEPFAR program, which began under President Bush and continues under President Obama, is credited with helping to put millions of people on antiretrovirals. By the time the drugs reached Africa, it was known that a combination of drugs worked much better than using a single antiretroviral. That meant a lower chance of developing resistance.

“Africa has benefitted from starting from day one with three drugs. You will not develop resistance if you are not replicating with your virus. So, a person who’s been on antiretrovirals, they don’t develop resistant organism because the organism isn’t dividing,” said Ambassador Goosby.

The challenge now is to put more infected people on antiretrovirals during tough economic times. Goosby says hundreds of millions of dollars have been saved by switching to generic forms of the drugs and using trucks and trains to transport them, rather than planes. PEPFAR will also work with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria to combine their purchasing power to drive down the cost of the drugs even more.

Goosby says they have to be smarter and more effective. He adds the American people should be proud of the many lives the United States has saved. These days, he sees a lot more people living with AIDS than dying from it.