The giant Gibe III dam, now being built on the Omo River in southwestern Ethiopia is a boon for some, a problem for others.

Supporters say it will provide electricity for millions of Africans. But others, like the British-based human rights group Survival International, say it will have a devastating effect on an estimated 200,000 people living in the area of the dam.

The Gibe III will curb the Omo’s season floodwaters, which provide water and silt to enrich local farmland.

The damage caused by the Gibe III dam could be far reaching, according to Lindsay Duffield campaigner at Survival International.

“The Omo River is the primary source of Kenya’s famous Lake Turkana, which supports the lives of 300,000 people who pasture their cattle on its banks and fish there. The dam will threaten their survival too,” she says.

Survival International is spearheading a campaign to stop the building of the Ethiopian dam and is urging the African Development Bank and other institutions to stop funding the project.

The Ethiopian government, on the other hand, says criticism of the hydroelectric project is fabricated and “far from reality.” The National Security Advisor to the Ethiopian prime minister, Abay Tsehaye, is quoted as saying the ongoing campaign against the Gibe III dam is an “empty attempt of some interest groups who do not want to see Ethiopia march towards development.”

Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has repeatedly stressed that no outside pressure would stop the Ethiopian government from completing the construction of the dam. “Ethiopia will accomplish the construction at any cost whether donors continue funds or not,” he said.

Upon completion, the $1.7 billon, Gibe III power project will have capacity to generate up to 1,870 megawatts of electric power, potentially enabling Ethiopia to export power to neighboring countries.

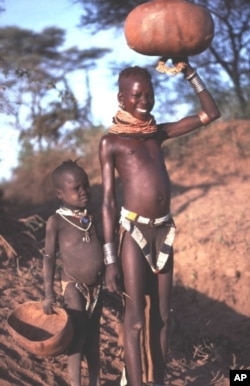

“The Ethiopian government is entirely unconcerned about the tribes living in the lower Omo Valley. It is not interested in consulting with them properly at all,” says Duffield. She says in 2009 the local regional administration for the area surrounding the Gibe III shut down a number of community associations, making it virtually impossible for the tribes affected to discuss their views of the dam.

The Ethiopian government further says Gibe III, aside from generating enough electricity to power the country several times over, will increase the safety of the downstream peoples by preventing the giant floods that sweep away livestock and people.

The criticism is “unfounded and unreasonable, [and] aimed to meet self interest under the pretext of the agenda by putting political and diplomatic pressure on the country, thereby, to seek money from donors,”says the national security adviser to Prime Minister Abay Tsehaye.

The Ethiopian government says with the construction of the dam it plans to boost the current 2,000 megawatts hydropower generation capacity to 8,000. “It’s important to point out that electricity generated by the dam is not going directly to Ethiopia,” Duffield says.

“A great deal of it will actually be taken across the border to Kenya because the governments have already made agreements. This is not an electrification project for the benefit of the people who are living in the area. When all is said and done, the tribes of the Omo Valley who are going to be affected by this dam are going to get precious little benefit from it,” Duffield explains.

Supporters say the Gibe III and other large hydroelectric dams provide cheap and efficient “green” energy that can supply electricity to millions. Duffield says the proponents have failed to explore other options first, like small scale hydropower dams, wind and solar power.

“A choice has been made to build what will be Africa’s tallest dam without considering the effects it is going to have on the people who live immediately downstream for it,” Duffield says.

Industry associations and lending institutions say they have retooled their evaluation procedures for large hydro dams and have started to apply new construction guidelines developed by a discussion forum, the World Commission on Dams.

In 2000, the commission issued a report saying decisions to build large hydro-electric dams must be guided by indigenous people’s free, prior and informed consent to the project. “[It was] a great move on the part of the commission at that time, but at this moment not clearly being applied to the Gibe III project in Ethiopia,” says Duffield.

She credits the World Bank for taking more account of environmental and social issues in its planning and for establishing a complaints procedure for affected tribal communities. But what the World Bank hasn’t done, she says, is to adequately implement the standard of free, prior and informed consent, which she says is absolutely vital to tribal people all over the world. “If they don’t have this very basic standard, which the World Bank should endorse, the results could be very devastating,” Duffield warns.

Upon completion, the Gibe III dam will be the second largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa, also providing electricity to needing neighbor countries. The dam wall will be 240 meters high, the tallest dam in Africa, and create a 150-kilometer-long reservoir. Salini Costruttori, an Italian company, started construction work on the project in 2006. Gibe III is due to be completed in 2012.