On June 7, 1944, a 20-year-old medic named Waverly Woodson plunged into the surf of Omaha Beach to drag four drowning British soldiers to safety. Injured by shrapnel, he’d already spent marathon hours treating other wounded men during the D-Day landings in Normandy. He collapsed from exhaustion shortly after.

William Dabney was also hit by shrapnel as he waded to shore through waist-deep water.

George Davison saw "bodies being blown to bits" as he ducked from German fire on the wide, flat beach.

All were members of the U.S. Army’s 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only African-American unit to participate in the Allied invasion to liberate France. Their orders: raise blimp-like balloons meant to deter enemy aircraft.

The men were praised for their heroism and, in Woodson’s case, recommended for the Medal of Honor.

But little record remains of their existence and their bravery – or the collective legacy of the more than 900,000 African Americans who served during World War II. At least until now.

Unearthing their stories

"The men in this unit themselves did not think anyone would care about the deeds of black men," says Linda Hervieux, a Paris-based journalist and author of a recently published book on the 320th called "Forgotten." "These men were treated terribly during the war. Segregation and discrimination were horrible things to live with."

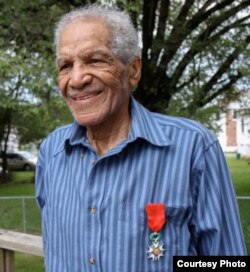

Hervieux stumbled on their story during the 65th anniversary of D-Day in 2009, when Dabney received France’s prestigious Legion of Honor.

"I thought their mission was really interesting, and it would be a shame to write just one newspaper article on it," recalls Hervieux who covered the story for the New York Daily News.

She spent three years digging through phone records and public archives in the United States and Europe for scraps of information. A dozen of the men were still alive.

Tracing their stories from civilian life to boot camp in the U.S., and then onward to war-torn Europe, "Forgotten" is as much a social history as a military one.

"It’s about Jim Crow America," Hervieux says, referring to laws enforcing racial segregation in the U.S. South, which also shaped military life. Black soldiers were subject to different rules and treatment. Few served overseas. Those who did fought in segregated battalions.

"All of them, to a man, said that the discrimination, the racism, the segregation, the race hatred they were exposed to during the war was absolutely devastating," Hervieux says of those she interviewed.

"Men from the South weren’t surprised; it was like back home," she adds. "But those from the North were staggered."

Broader picture

"Forgotten" fits into a broader retrospective about how minority soldiers were treated during last century’s wars – not only in the U.S. but also in Europe. That includes Britain, where the largely forgotten contributions of Indian troops fighting alongside WWI allies is the subject of another recently published book, "For King and Another Country."

More than a million Africans also served colonial powers during WWII, with the survivors receiving little compensation. Algerian veterans who sided with France during Algeria's bloody war of independence are also still claiming greater recognition.

"Many people ask why we’re dredging up this dirt from the past," Hervieux says. "But there’s a whole line of thinking that believes we must absolutely confront the past and remember it."

For the soldiers of the 320th Battalion, WWII was also liberating. Stationed in England before the allied landing, they were treated as heroes – although white GIs tried to have them banned from pubs and cinemas.

"A lot of Britons had never met a person of color before, and they did not have preconceived notions of what to expect," Hervieux says. "So they were welcomed with open arms as Americans, as treasured allies."

Medal for Woodson

"Forgotten" is earning sterling reviews and Hervieux is currently on book tour in the U.S. But one battle is unfinished.

On her website is a petition to posthumously award the Medal of Honor to Waverly Woodson, the medic who worked tirelessly to save lives on Omaha Beach. Despite being recommended for the highest military honor for his service, he was instead given the lesser Bronze Star.

Indeed, no black soldiers were given the Medal of Honor during the war. An Army study later found a climate of racism influenced the awards process, and in 1997 seven were awarded the medals, six posthumously.

Woodson, who died in poverty more than a decade after the war, was not among them.