The United States and China have agreed to do what they can to avoid a currency war, according to a White House statement issued before the opening of the Group of 20 nations meeting Sunday in the Chinese lake city of Hangzhou.

The move reflects rising fears that some countries might forcibly devalue their currencies to protect falling exports, and hurt their competitors.

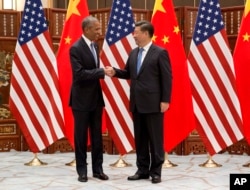

"The United States and China jointly reaffirm their G-20 exchange rate commitments, including that they will refrain from competitive devaluations and not target exchange rates for competitive purposes," the White House said Sunday, a day after a meeting between U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

"China will continue an orderly transition to a market-determined exchange rate, enhancing two-way flexibility. China stresses that there is no basis for a sustained depreciation of the RMB. Both sides recognize the importance of clear policy communication," the statement said.

The move is meant to put at rest fears in some quarters, particularly in Japan and South Korea, that China might devalue its currency to check the slide in its exports, which became more intense in the first half of this year.

Japan, China and South Korea were involved in competitive devaluation of their currencies last year. China's sharp devaluation in August 2015 severely jolted the world markets. But Beijing blamed Japan for starting the process of devaluing the Yen to boost its own trade at the cost of Chinese exports.

The specter of shrinking international demand and the recent Brexit vote in Britain has given rise to fears another round of devaluations may be in the offing.

Brexit fears

European countries are also expected to push the G20 to adopt a binding commitment on curbing devaluations.

"Competitive devaluation of currencies is bad for everyone. We are in favor of any move to stop it. We will go by the decision taken on this issue at the meeting of G20 finance ministers," Schinas Margaritis, spokesman of the European Commission told VOA.

There are fears Britain's decision to move out of the European Union might severely damage the British economy and hurt some countries that are closely connected to its business. The final outcome is not known, but there are fears about instability in the British pound.

Obama met British Prime Minister Theresa May on the sidelines of the G-20 meeting for the first time since she took office. They discussed ways to enhance business connectivity between the countries.

Pledges by finance ministers

The G20 meeting will be a test of whether heads of states will put their stamp on a pledge taken by their finance ministers and central bank governors earlier to "reaffirm our previous exchange-rate commitments, including that we will refrain from competitive devaluations and we will not target our exchange rates for competitive purposes," .

An important question is whether a principled stand taken by the heads of states from 20 wealthier nations is workable, because market forces often tend to prove more powerful at a time of currency turmoil than the might of governments.

"I don't think such agreements would be meaningful," Micheal Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University's Guanghua School of Management said. He pointed out there is extremely weak demand in international trade, and every country would try to compete with others to expand its exports. Besides, most major currencies operate on a floating rate, which allows little room for governments to intervene.

Escape route

The proposal may face some resistance. There might be an attempt to insert an escape clause to allow governments to interfere in currency markets to avoid a local crisis.

After the last meeting of finance ministers, Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said the agreement does not mean his government cannot intervene to check a one-sided move by the Yen.

"What the G20 is talking about is arbitrary intervention, which is different from responding to a one-sided move," he said.

Some experts ask whether China's assurances could be relied on at a time when its global markets are shrinking rapidly. Chinese exports fell by an unexpectedly wide margin of 4.4 percent in July, prompting government economists to predict a dismal scenario in the rest of 2016.

"China pledged at the G-20 finance ministers' meeting in February 2016 that it will not [de]value its currency. But it has devalued the Yuan twice after that," Daniel C. Park, a compliance director with the G-20 Research Group, a think tank affiliated to the University of Toronto, told VOA.

In its report, the G-20 Research Group advised world leaders to go beyond making pledges, and devise a plan about "how to collectively respond toward member countries who fail to uphold the pledge and proceed to fix their currencies".