“Creole isn’t about a specific skin tone or country, it’s about a culture,” said Mona Lisa Saloy, author of the poetry collection Black Creole Chronicles.

“It’s food, it’s music, it’s architecture, it’s style and it’s traditions,” she told VOA. “There are millions of Creole people in countries across the world and, still, we are all so much more alike than we are different. We create beautiful cultures everywhere we go, and I think that’s evident here in Louisiana.”

Linguists estimate as many as 10,000 people still speak the French-based language Louisiana Creole. Many more in New Orleans and across the state consider themselves part of a culture that draws tens of thousands of people to events including last month’s Festivals Acadiens et Creoles, summer’s Creole Tomato Festival, and spring's Tremé Creole Gumbo & Congo Square Rhythms Festival.

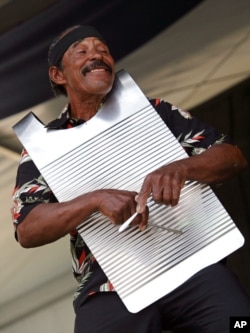

But for many locals and visitors alike, it’s the everyday evidence that demonstrates how pervasive Creole culture really is in Louisiana. The state’s stages and airwaves are frequented by the driving, rhythmic scrape of a washboard virtuoso or by the up-tempo syncopation of zydeco music accompanying an accordionist. Its restaurants emanate mouthwatering scents from rich, complex flavors including gumbo, hot sausage, red beans and rice, and shrimp étouffée.

“To celebrate Creole culture is to wake up and live in New Orleans,” said Christina Bragg, a member of the Mahogany Blue Babydolls, a parading group for Black and mixed-race women.

“Celebrating ‘Creole’ is celebrating our day-to-day lives. The food we eat. The music we dance to. The way we gather with friends to parade during Mardi Gras," she said. "Every day I open my eyes and breathe, it’s a celebration of Creole culture, because that’s who I am.”

Difficult to define

“No matter where in the world you find Creole culture, you’ll see key similarities to what we have here in Louisiana,” said Saloy, who was Louisiana’s poet laureate from 2021 to 2023.

“Architectural styles common in New Orleans like the Creole Cottage or the Shotgun home can be found in other places with Creoles, such as in other parts of the American South and the Caribbean,” she said. “Much of our music derives from the rhythms of Africa and the Caribbean, as does much of our food — elements of gumbo such as the long rice and okra, for example, or the prevalence of beans.”

While certain elements of Creole culture bridge oceans, how one defines the word "Creole" — and specifically the inclusivity of that definition — changes from region to region, and even from person to person.

It comes from the Portuguese word crioulo, which itself derives from the Latin creare, meaning “to create.” It was used during the European slave trade to denote a slave born in the New World as opposed to someone born in Africa. The word then took on different meanings in different places. Creole cultures in much of Africa and part of the Caribbean, for example, came to define an ethnic group made of people with a mix of African and non-African heritage.

In Louisiana, the definition has shifted over the years, and among households.

“Here, the definition kind of depends on who you ask,” said Vance Vaucresson, a New Orleans-based Creole and owner of a local restaurant, the Vaucresson Sausage Company.

“I prefer an inclusive definition,” he said. “By that definition, anyone born in Louisiana could be Creole. During our colonial era, it was meant to differentiate people born in the Americas — usually of French, Spanish or African descent — from those born in Europe or Africa who now found themselves here.

“I like that better than the other definition,” he added, “which says that Creole people in Louisiana are specifically related to the ‘free people of color.’ I like the more inclusive definition better because it unifies us by culture. Black, white or mixed race, it doesn’t matter. If you’re born here and embrace the culture, you can be Creole.”

An evolving term

In 18th- and 19th-century Louisiana, that more inclusive definition was the most accepted. White people with recent European ancestry were just as likely to call themselves Creole as mixed-race residents with African ancestry.

White Creoles claimed the term because it differentiated them from white people who were coming from Northern states after Louisiana was purchased from France in 1803. Mixed-race Creoles, too, claimed the term because it differentiated them from slaves.

“Slavery was so entrenched in the United States, Louisiana included, so I think free people of color or mixed-race people were happy to have a term that raised their social standing,” said Don Vappie, a Creole jazz musician in New Orleans. “It was more of a three-tier racial hierarchy here, instead of the two-tiered Black-or-white experienced elsewhere in the U.S.”

After the American Civil War, however, much of that racial nuance in New Orleans disappeared.

“Creole or not, white people had more in common with white people and Black people had more in common with Black people,” Vappie told VOA. “And white people didn’t want to use a term for themselves that was claimed by anyone who was Black.”

As a result, it’s rare to find a white person in Louisiana today who identifies as Creole.

“Nowadays, it’s definitely more of a Black person thing,” said Bragg of the Mahogany Blue Babydolls. “But there’s still so much diversity in Creole culture. You have Creoles with very dark skin, Creoles who basically look white, Creoles with Black features, Creoles with lighter brown skin and green eyes. It’s people who have been from the region for a long time, and it’s a unique thing.”

And while French Creole is spoken less frequently as older generations pass, there are still many Louisianians who are proudly Creole and want to see its traditions survive.

“I want to see more people learn about Creole culture, no matter what their skin color is,” Vaucresson said. “New Orleans has Irish Creoles, Italian Creoles, African Creoles, French and Spanish Creoles, and more. And they all have their different versions of food. At my restaurant, we try to keep those old Creole dishes on the menu so our past never disappears.”

Saloy believes Creole is firmly connected to African culture and should stay that way.

"The ingredients in our food, the rhythm in our music and dance, the details in our architecture — it’s all connected to West African culture,” she said. “And when those Africans were taken from their lands and shipped across an ocean, even though they were enslaved, they managed to make something beautiful again. That’s our heritage.

“For years, white people didn’t want to have anything to do with Creole,” she added. “So I don’t think they should be able to claim it now that it’s become in vogue.”