The World Health Organization is fearful that funding cuts announced by the U.S. will deter its efforts to control the spread of the coronavirus in Africa. Aside from coronavirus, the WHO is concerned that vaccine-preventable diseases could also spread as countries are forced to cancel vaccination programs.

President Donald Trump’s decision last week to suspend U.S. funding for the World Health Organization could deter the continent’s ability to stamp out not only the coronavirus but other deadly diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS, a senior WHO official told VOA.

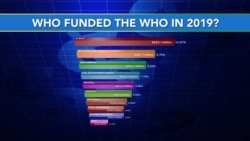

The U.S. is the main funder of WHO programs linked to malaria, polio and HIV/AIDS in Africa. Currently, the U.S. has pledged $400 million to the WHO’s $4.8 billion 2020-2021 budget.

While its pledges are mostly locked in for this year, WHO officials expect the U.S. funding suspension to start biting in 2021.

Michel Yao, emergency operations program manager at the WHO’s Regional Office for Africa, spoke to VOA via a messaging app.

“This support is what helps to provide technical support or even to have a technical position in a country. Some of them, a program like malaria, need to have continued support based in a WHO country office. So all these technical positions and also work that is required while convening experts to work on a specific guideline for a given disease, this also the funding was helping, and sometimes even some of the supplies on HIV issues. So, all of this, of course, will suffer if this gap is not covered," said Yao.

For COVID-19 prevention efforts, the WHO has repurposed many of its staff to deal with the outbreak. While money has been set aside for 2020, question marks hang over those roles for next year.

“In the case of COVID, some of these technical people have been repurposed. Of course, lots of them got their contracts extended but maybe from next year, if we don’t have enough funds then we’ll have to cut on staff. It will also affect [things] because some of them have been repurposed based on that. If this shortage continues it will definitely affect our HR plan for next year,” said Yao.

Yao denounced claims that the WHO was slow to respond to the coronavirus outbreak or that the organization has been too “China-centric.” He said a team of international experts was established January 1 and sent in early February to Wuhan, where the original outbreak occurred, to report on the scale and danger of the outbreak.

The WHO, in partnership with other U.N. agencies, has begun delivering personal, protective equipment around Africa by using Addis Ababa as its central cargo hub. World Food Program planes last week began delivering emergency health workers across the region.

But a sheer lack of basic and technical equipment such as ventilators and clinical care beds are troubling many policymakers in the region. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa CDC, told reporters last week that at least 10 countries in Africa have no ventilators whatsoever.

Another major concern for health authorities in Africa is the impact the COVID-19 crisis will have on other diseases. According to the WHO, Guinea, Ethiopia, South Sudan and Chad have already postponed mass vaccination campaigns for measles that were due to take place between March and June.

The WHO fears it will see vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, rubella, polio and diphtheria become more commonplace.