A devastating new wave of U.S. coronavirus cases is forcing school districts to consider again closing classrooms and returning to remote online instruction, creating educational hurdles that can be especially severe for millions of poor and minority students.

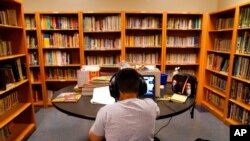

The challenges are evident to students like Devon, who didn’t give his last name when he spoke with VOA outside Hialeah-Miami Lakes High School in south Florida, where classroom instruction is increasingly rare.

“It’s one of a few days I can attend in-person classes,” Devon, who is African American, said. “It’s been difficult to maintain my grades since we started virtual learning last March. My concentration level is higher in the classroom.”

Minorities constitute 97% of the high school’s student body, and 8 of 10 students are economically disadvantaged.

Research by the independent news publication Education Week suggests in-person learning yields superior educational outcomes for primary and secondary students — and that the pitfalls of virtual instruction are especially pronounced in minority communities and for those living in poverty.

Since March, the Miami-Dade school district, the nation’s fourth largest by enrollment, has dealt with a series of problems transitioning to remote learning. They included adequate laptop distribution, problems logging into virtual classrooms and minority communities lacking high-speed internet service.

Some educators and parents say prolonged reliance on virtual instruction will stunt the educational growth of untold numbers of students.

"I worry about the long-term impacts, a lack of social interaction and students who don’t get extra help when they need it,” said Nicolas Leduc, a fourth-grade teacher in Bradenton, Florida.

Outcomes may vary from one school to another and also may depend on the ability of parents to oversee their kids’ learning at home.

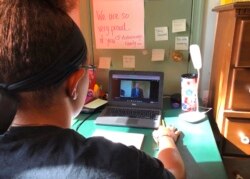

"I think our children are doing well,” said Karen Cryer Douthit, a Black parent whose 6- and 10-year-old sons attend Holy Cross Lutheran School, a private, religiously affiliated grade school in Miami. She and her husband are working from home during the pandemic, unlike many other minority parents.

"We’re at home and able to give our kids the attention to help maintain focus and follow along with the online lesson as a teacher is moving forward. But for those children whose parents or guardians don't have that opportunity or that advantage, those students will be left behind,” Douthit told VOA. “I don't personally think they will be able to catch up.”

Learning disruptions

In New Orleans, weekly primary and secondary school attendance is down 10 percent from a typical year since August. A majority of the district’s 45,000 students come from low-income and minority families. Students of color make up 91% of the city’s public school students.

In an effort to help students with virtual learning, the school district purchased additional laptops and 8,000 internet hot spots to provide prepaid unlimited internet access for 12 months.

The effort may help New Orleans avoid negative educational consequences that became apparent after a very different kind of disruption in the city’s past.

Five years after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, forcing schools to temporarily close, a third of the city’s students were held back a grade level, according to a study by Columbia University. A 2015 survey found the average 7-year-old student at the time of the hurricane was more likely than counterparts in all but two other cities to be neither enrolled in school nor employed a decade later.

Online learning

Today, many cash-strapped school districts have struggled to address learning barriers minority students are disproportionately experiencing during the pandemic.

“My biggest concern is these kids might lose out on years of education,” said Douthit’s husband, Marc Douthit. “We have got to make sure we look out for disadvantaged urban children who lacked educational support even before the pandemic.”

Education researchers say some school districts are making a concerted effort to evaluate students’ remote learning needs, increase student participation and monitor daily schoolwork.

But educators like Broward County Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie acknowledge problems will persist so long as classroom instruction is interrupted.

“Parents need to have a choice between keeping their children at home or allowing them to return to in-person classes, especially if they are struggling,” Runcie said.