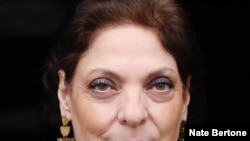

It was early March 2020. Karen Nascembeni and Steven Richard, her husband of 20 years, were sick. Doctors told them it was a sinus infection, plus an unknown virus. They prescribed antibiotics and sent them home.

“I mean, this was the Wild West back then,” says Nascembeni, who was later diagnosed with COVID-19. “No one knew what this thing was and how serious it was … we were just so sick. And what happens is you get so oxygen-deprived that you don't have your wits about you.”

Her husband, Steven, was so weak, she remembers him pulling a chair from the dining room into the family room to sit on because he did not have the strength to get up from the plusher, lower seating.

“We were completely lethargic, like on a level I had never experienced before, and I've had very serious pneumonia for months. It was way worse than that,” Nascembeni recalls. “There was definitely a sense of being delirious, because we were so oxygen- deprived.”

A doctor finally suspected they had contracted COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, and advised them to go to the hospital emergency room. Medical personnel attended to Nascembeni’s husband first.

“We had to wait in the car, and they came out. They took him right away. And he turned around, and he blew me a kiss and said, ‘I love you.’ And that was the last time I saw him,” she says.

That was on March 17, 2020 — St. Patrick’s Day. Steven Richard died a week later at the age of 58. He was among the first people in Massachusetts to die of a disease that would soon ravage the United States — so far killing more than 517,000 people — and more than 2.5 million worldwide, according to Johns Hopkins University. Richard’s 99-year-old father, Earl, a World War II veteran, died five days after his son, as did a close friend of the couple’s.

But Nascembeni, the general manager of a Massachusetts theater, knew none of this. She had been placed in a medically induced coma after her own condition deteriorated. She awakened to a radically different world 31 days later.

“I woke up to learn that my husband, my father-in-law, my friend, had all died. And I had lost my job, because I run a major theater, and we were shut down,” Nascembeni remembers. “I basically had lost just about everything, including, nearly, my own life.”

She spent weeks undergoing rehabilitation and another four months with her sister’s family, regaining her strength and relearning how to walk.

During her recovery, Nascembeni was buoyed by the support of family, friends and co-workers from the North Shore Music Theatre, who raised money for a scholarship fund they had established in Richard’s name.

“Steven was probably the kindest man I've ever met in my lifetime. He was the type of person who always did for others,” Nascembeni says. “He was the kind of person that you know, small children and animals would just leap into his arms. He was this beautiful, tender soul. I think that he would be stunned to find how grief-stricken people are over his loss.”

Richard, a contractor, was doing work on their house just before he died. Nascembeni says more than 80 people came together to finish his renovation so she could move back into the house after her recovery. A year later, they still bring her meals.

That outpouring of love and support helps Nascembeni carry on despite all she has endured over the past year.

“Amidst all of this grave sadness and loss, I was blessed with an incredible amount of love and support,” she says. “And through that, I think I just focused on gratitude, which was my saving grace. You know, rather than thinking about, ‘Gosh, I wish I had Steven for another 30 years,’ I thought, ‘I am so lucky that I (had) this incredible man for 30 years.’”

Nascembeni is now experiencing unexpected health issues in the aftermath of surviving COVID-19.

“When I left (the hospital), my blood work was good. Three, four or five months later, all of a sudden, I'm wearing a heart monitor for two weeks because I'm having extra heartbeats. And then my kidney levels got elevated,” she says, “So, you don't know which version of this you're going to get.”

Nascembeni's hair fell out during her illness. She used to work long days at the theater but now cannot imagine working 12 to 14 hours a day. She understands that people are tired of the pandemic, but she hopes they will continue to try to keep themselves safe so they will never have to endure, or witness, what she has.

“I saw people in the COVID wing when I was recuperating that had horrific lifelong permanent pinched nerves in their necks, nerve damage from these positions that they were put into in intensive care,” she says. “People are still dying in droves every single day. And you don't want to risk getting this, because the lifelong permanent damage that you can experience is frightening.”