Do pandemics such as COVID-19 divide or unite societies?

Most historians would answer with the former. Pandemics — particularly big, killer disease outbreaks of mysterious origins — they say, tend to fuel scapegoating, hate and mass violence.

The 14th century bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, is often cited as Exhibit A of this thesis. Blamed for the deadly outbreak, Jews and other minorities in Europe were massacred.

Another example is the cholera outbreaks of the 19th century, which spawned violent attacks on hospitals and doctors across Europe and the United States.

Yet when the bubonic plague struck again, it did not prompt large-scale attacks on Jews or other minorities. Nor did the outbreaks of typhus in the 15th century, smallpox in the 16th century or the deadliest of all pandemics — the Great Influenza of 1918-19, commonly referred to as the Spanish flu.

To Samuel Cohn, a professor of medieval history at the University of Glasgow who has researched epidemics going back to ancient Greece, this shows that contrary to accepted wisdom, not all pandemics lead to hate and violence.

More often throughout history, Cohn says, massive disease outbreaks have tended to bring communities together, fueling a surge of compassion and volunteerism. He calls these “diseases of compassion.”

Cohn calls COVIID-19 a disease of compassion akin to the Spanish Flu, during which many Americans mobilized to help the sick and needy.

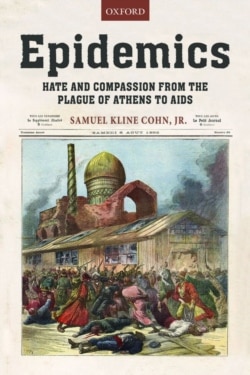

Although COVID-19 has been blamed for inciting anti-Asian hate crimes around the globe, Cohn says these incidents “pale in comparison with the mass volunteerism and goodwill” generated by the pandemic. In this interview, condensed and edited for clarity, Cohn, author of “Epidemics: Hate and Compassion from the Plague of Athens to AIDS,” discusses the long-term consequences of epidemics and how COVID-19 will change society.

In your book on epidemics, you challenge several long-held assumptions about the relationship between disease and hate. What have historians gotten wrong about how epidemics impact societies?

Historians, when they look at diseases collectively, almost exclusively emphasize the negative psychological aspects of epidemics and pandemics, that they universally, across time, have produced hate, blame and division in society.

You get individual studies by historians that [show] just the opposite. But when these generalized books are written … it's been the negative that's been emphasized at the exclusion of many other types of reactions, and no distinction is made for different types of disease.

What was so exceptional about the Black Death?

It is unique in history in the size of the destruction that comes directly out of the disease itself. In terms of per capita mortality, it was the worst epidemic, certainly in Europe and in the Middle East, that we know of — one that after the Black Death of 1347-52, kept coming back well into the 19th century.

[Yet,] the persecution of outsiders — of Catalans in Sicily, beggars in Narbonne [France] ... and the Jews through the Rhineland — did not happen everywhere. In the Middle East, for example, we have very little evidence of this type of mass persecution and blame placed on any minority.

You draw a distinction between a “disease of compassion” and a “disease of hate.” Which is COVID-19?

I'm sure I'll get attacked for this, but COVID-19 is a “disease of compassion,” very much like the Great Influenza.

Reports of compassion are very much in the headlines. In the U.K., [there was] Captain Tom and the mass donations he was able to raise for the National Health Service. The clapping [for front-line workers] every Thursday night through lockdown; the singing from [balconies] in Italy, Spain and elsewhere.

But one thing that's not emphasized … is mass volunteerism. In March, the U.K. Health Ministry called for 250,000 volunteers to help with various things like deliveries to those being shielded, as well as ultimately becoming guinea pigs for the new vaccines. And people laughed. Within two weeks, however, well over 1 million people had volunteered, and the government didn't know how to handle it.

To be sure, there have been incidences of blame of other countries, especially China, and hate crimes even against victims, but these pale in comparison with mass volunteerism and goodwill.

In general, how do epidemics change societies?

They can have very salubrious consequences. For instance, with cholera, as bad a disease as it was in the 19th century, it was a real spurt for improving water systems and hygiene. And the Great Influenza of 1918-19 improved the status of nursing, with new educational investment, a new public health mentality, and new institutional research centers for virology. The whole science of virology really sprang from 1918.

With the Black Death and its repeated plagues, it introduced the whole notion of a public health system, of quarantines, of protection, of health passports and certificates. And they worked, to a certain extent.

How is COVID-19 likely to change society, social norms and routines?

It’s a hard one. The economic consequences of COVID-19 present the most disastrous picture, especially for young people now finishing university or in their early careers. The current predictions, however, vary radically, from notions that the economy is primed to rebound quickly, becoming bigger and better, to predictions of a generation or more being lost.

In terms of behavior, it's exacerbating a trend that was already there, like the closing of High streets for online shopping. It’s sped that up tremendously, and people think that this trend will continue after the virus has dissipated.

Finally, given what we know about its lethality and infectiousness, had COVID-19 broken out in the pre-modern era, how deadly could it have been?

It would not have been nearly as bad as the Black Death or even the Influenza of 1918-19. I don't think COVID-19 spreads as efficiently as either one of them.

The other thing — one that's not talked about enough in looking at the future space of populations — is that the young are mostly spared. With other diseases, when they first strike, the young are killed, probably in greater percentages than the general population.

COVID-19 doesn’t have that aspect. What it is doing — and it’s hard to talk about it, mainly because it is probably too sensitive of a subject — is that by killing off the very old and those who have underlying health problems, you’re lessening the dependency ratio of the communities in the long run.

I’m not saying good or bad … but the consequences of this will be new. Where the disease is hitting hard and seems uncontrollable, it’s going to change demographic structures to a certain degree.