With billions of lives and trillions of dollars depending on a vaccine for COVID-19, scientists around the world are working to create an effective and safe candidate as quickly as possible.

By some optimistic estimates, the world could see a vaccine in the coming months. Or it could take longer than 18 months. Or scientists may not be able to manufacture a vaccine at all.

If scientists succeed, there will likely be enormous advantages for whoever controls it.

Competing to be the first

"The first country to the finish line will be first to restore its economy and global influence," said Dr. Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration.

He said in a recent article published in The Wall Street Journal that as initial doses will be limited, a country will focus on inoculating most of its own population first.

The priority for any country is to protect its own citizens, and governments may reserve supplies produced within their borders for their own use and stockpile doses for future outbreaks. Exports will likely be prohibited. Experts warn that even after development of a successful vaccine, it could take years to make enough of it to help other countries.

"It's really a case where health meets economics and politics," said Bryan Mercurio, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong and an expert on drug patents. He said the way that the global patent system works plays a critical role in how a government will approve a vaccine.

While there are more than 100 vaccine candidates in development worldwide, "there will likely be one winner," Mercurio told VOA in an email.

He said the global patent system favors a "winner-take-all approach, the winner is like someone just 'hit the jackpot.’ The rest of the efforts will go unrewarded."

With so much at stake, experts warn the rift in the relationship between the U.S. and China could spill over into the vaccine approval process.

Mercurio described what could happen next as "political gamesmanship.” He predicted China and the U.S. each would try to persuade countries to approve its vaccine first.

"China will fast-track the approval process for one of its home-developed vaccines, while not fast-tracking a foreign-developed vaccine. In this way, the only vaccine which can be marketed and injected in China would be the Chinese-made vaccine," Mercurio said. "The U.S. could do the same, so as to benefit its local developers."

‘A battle that China cannot afford to lose’

Since the early days of the outbreak in China, the government has made clear that it is looking for a national champion in this global race for a cure. A pro-Beijing newspaper, Global Times, called the campaign "a battle that China cannot afford to lose."

Since late February, shortly after vaccine development began, Chinese officials have repeatedly assured the country that their approach is among the most advanced in the world.

Wang Zhijun, a biological products quality control expert with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said again and again that China “will not be slower than other countries.”

"In China, the development of a vaccine was viewed as if it were an Olympic game," Huang Yanzhong, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, told VOA in a telephone interview.

" 'Be the first to the finish line and win the gold medal' is everything. Unless you are the first, the race is meaningless," he said.

Clearly, developing a vaccine represents a golden opportunity for China to raise its global stature. Beijing was criticized for its early mishandling of the crisis. Now it is seeking to change perceptions through “mask diplomacy” to portray itself as a generous and efficient power. A successful vaccine could redeem Beijing’s role from coronavirus source to savior.

"We're blaming the Chinese for what happened. But the bottom line is we depend on the masks that they make. If they are the ones that invent the vaccine, will we say no?" Madeleine Albright, former U.S. secretary of state, said in a recent interview with Australia’s ABC Radio.

Balancing safety, speed

Yang Zhanqiu, deputy director of the pathogen biology department at Wuhan University, said China’s governance system gives it an advantage over other countries in fast-tracking vaccines.

"China’s institutional advantage lies in the central government’s ability to organize and concentrate scientific and technological forces across the country and work together," Yang wrote in an email to VOA.

He said the five vaccine candidates under development in China have provided the country with more options for evaluating the effectiveness of different vaccines and choosing which to select for broader use in people. He predicted that U.S. teams with fewer candidate vaccines would lag behind China.

Already, only weeks after its scientists released the genetic sequence of the coronavirus, China said in early March that the first vaccines could be in "emergency use" by September.

Other Chinese virologists have said the rush to develop a vaccine should not cause researchers to take shortcuts.

Jiang Shibo, a professor at the School of Basic Medical Sciences at Fudan University in Shanghai, wrote in a column published in Nature earlier this year: "My worry is that this could mean a vaccine is administered before its efficacy and safety have been fully evaluated in animal models or clinical trials."

"Vaccines are a matter concerning all human beings, and you must not rush for success," Dr. Fang Guodong, a senior medical officer at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, said in a telephone interview.

US remains confident

Gottlieb, the former FDA commissioner, acknowledged that China might have a coronavirus vaccine available on the market before American trials have been completed. But he said it might not be very effective.

"There’s a risk that China may get to a vaccine first. I don't think their [vaccine] is very good, but they may get it to the market before we do," Gottlieb said on CBS's "Face the Nation” in late April. "I think that is a concern."

Peter Smith, the former chair of WHO's Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, said that the world health body was encouraging more countries and companies to join the effort to produce a safe, effective vaccine.

"The more groups that are trying to develop a vaccine, the better. We will certainly need more than one to meet the required capacity," he told VOA in an email.

Researchers at Oxford University, where one of the leading efforts to develop a vaccine is underway, also said a vaccine might be available as soon as September. The school said in a press release that under the best-case scenario, it could have an efficacy result from a phase-three trial by this fall "to show that the vaccine protects against the virus, alongside the ability to manufacture large amounts of the vaccine."

In the U.S., the Trump administration is organizing a Manhattan Project-style effort to drastically cut the time needed to develop a coronavirus vaccine, with the goal of making 300 million doses of vaccine available by January.

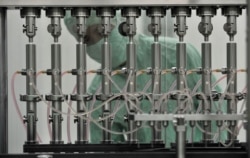

The effort by the U.S. government is so intense that it is building production lines before it has a vaccine ready to produce.

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the federal government’s top expert on infectious diseases, told reporters last month that the country could not afford to wait.

“You don’t wait until you get an answer before you start manufacturing,” he said.