Blue skies over Beijing. Unusually clean air in New Delhi. Rare views of the hills around Los Angeles.

One of the few pleasant side effects of COVID-19 lockdowns has been the widely observed drop in air pollution because of reduced industrial and manufacturing production and auto emissions.

Those clearer skies may have resulted in more than 7,000 fewer premature deaths and nearly 7,000 fewer asthma attacks, according to new research.

"The COVID lockdown is not sustainable and it's not the way we want to reduce air pollution," said study co-author Kristin Aunan, senior research fellow at the Center for International Climate Research.

However, she added, the research helps demonstrate "the large impacts of air pollution that we have, all the year through, year after year."

The research has not yet been reviewed by other experts for accuracy. It is available at the online preprint site MedRxiv.

"This is by far the most comprehensive and detailed look at the air quality impacts of shutdowns related to COVID that I've seen," said University of British Columbia environmental health professor Michael Brauer, who was not involved in the research.

However, Brauer finds the health impact estimates "overly simplistic."

"Yes, there will likely be some health benefits," he said. "But I'm a little bit hesitant to say that this is actually what's going on."

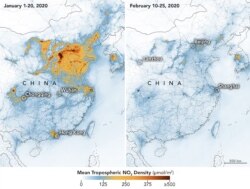

The researchers used satellite data and readings from more than 10,000 air monitors in 27 countries and compared those with figures from the previous three years, factoring in weather variations.

They studied three pollutants: nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3) and PM2.5, the smallest pollution particles, which penetrate deepest into the lungs and cause the most damage.

The group then plugged pollution numbers into existing formulas for health effects.

"We know quite a lot about air pollution's impacts on health," Aunan said. NO2 pollution triggers an estimated 4 million asthma cases in children each year worldwide. O3 and PM2.5 contribute to between 4 million and 9 million annual premature deaths globally, from strokes, heart disease, lung disease and acute respiratory infections.

Overall, Aunan and colleagues found a 29% drop in NO2. O3 declined by 11% on average, but differences were highly variable. PM2.5 levels were down significantly in some places but not others.

The declines added up to roughly 7,400 fewer premature deaths and about 6,600 fewer children's asthma cases in just the two weeks following national stay-at-home orders.

In India alone, the authors estimate, cleaner air spared 5,300 lives in the two weeks following the pandemic lockdown. China may have lost 1,400 fewer lives from pollution.

In the unlikely and unwelcome event that lockdowns were to remain in place all year, the researchers calculate that the figures would grow to 780,000 lives spared and 1.6 million asthma cases avoided in the 27 countries studied.

"I'm not too sure I should use the word 'silver lining' for this serious situation," Aunan said. "I would call it an unintentional co-benefit."

NO2 may have fallen more consistently than O3 or PM2.5 because those two pollutants travel farther and linger in the atmosphere longer, the authors say. Dust storms and wildfires can contribute to PM2.5.

"Probably the most important complication," the University of British Columbia's Brauer added, "is that there are other [pollution] sources that we have not stopped." Power plants are still burning fossil fuels for electricity, he noted. And in India, many people are still cooking over fires.

Brauer agrees there are likely some health benefits to the reductions in pollution, but he is skeptical that the researchers can accurately predict how many lives have been saved.

For example, "people are staying home more. For some of these pollutants, being indoors offers you some protection. People may be more or less physically active than they normally are."

He says researchers can go back and study the actual impacts after the pandemic is over.

"There's just so many things that are different now, I guess I'm not really sure [the study] really tells us anything," he said.

"These numbers do need to be interrupted with a lot of caution," Harvard University biostatistician Francesca Dominici said. However, she added, "I do think that it makes sense to talk about potential health benefits."

The study's most valuable insight may be into how different pollutants respond to this unprecedented situation, she added.

"We can learn from this opportunity how to regulate pollution when we go back to normal," she said.

Other researchers are looking into whether dirtier air makes people more susceptible to COVID-19, as it does for other infections.

That would add a layer of difficulty to the pandemic, Brauer said.

"If this continues, say in China and India, into the next winter when they typically have their worst air quality, is there going to be any interaction there? That's actually what concerns me more," he said.