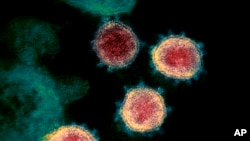

New research provides encouraging signs that COVID-19 vaccines may continue to provide protection even as the coronavirus mutates into variants.

A less understood branch of the immune system, T cells, may step in when variants undermine the first line of defense, antibodies, according to a new study.

Antibodies block viruses from entering cells, which prevents infection. Several variants have raised concerns because antibodies do not work as well against them.

T cells do not prevent infection. Instead, "as soon as you are infected, they're actually needed to clear the virus from your body," said Erasmus University Medical Center virologist Rory de Vries, co-author of the new research.

De Vries and colleagues studied blood samples from 121 Dutch health care workers who had received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Antibodies from those samples were two to four times less potent against the variant first spotted in South Africa than they were against the original virus.

'Didn't really seem to care'

The T cells were a different story.

"The T cells didn't really seem to care" whether they were facing the original virus or a variant, de Vries said. "They were just as active against all viruses."

If a variant is able to evade antibodies, he said, "these T cells might swing into action" and stop them from spreading in the body. A person might get infected but not get sick.

"It's important to not blindly focus on antibody responses and assume that if an antibody response to a variant is four times lower that the vaccine works less," de Vries said. Even if antibodies do not work as well, he added, "there are different components of the immune system that could very well protect us from disease."

Other experts were cautious.

There is a lot that scientists do not know about how important this side of the immune system is, noted New York University Grossman School of Medicine virologist Nathaniel Landau, who was not involved with the study.

"I think the critical question is: Is the protection that's provided by the vaccine caused by the antibodies, or is it caused by the T cells, or is it both?" he asked. "It's pretty clear that antibodies are very important. What we don't know yet is how important the T cell response is."

Based on animal studies, he added, "my guess is that it is very important."

Cancer patients with impaired antibody responses were more likely to survive COVID-19 if they had stronger T cell responses, according to another study.

"The bottom line is, yes, there is immunological evidence that [vaccines] are priming more than just neutralizing antibodies and that these other parts of the immune response are important," said University of Pennsylvania immunologist John Wherry.

Relative roles unclear

It is not clear what the relative contributions of antibodies and T cells are, he added, "but it is likely that vaccines will provide some protection from severe disease, even if antibodies are suboptimal," he said.

The new study looked only at the Pfizer vaccine. The Moderna vaccine is very similar, and experts said the results likely would be, as well. It is less clear how they translate to the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccines, which are a different type. Those studies are up next.

Another important finding: One dose of vaccine may be enough for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

One dose of the Pfizer vaccine produced the same level of immune response as two doses did in people who had not been infected before, noted study co-author and Erasmus University Medical Center virologist Corine Geurts van Kessel.

Given the limited supply of vaccines, "you can imagine that in countries where a lot of people have encountered COVID that this can really make a difference," she said.