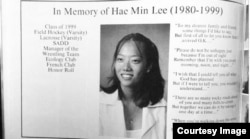

Before 2014, if you Googled the name “Adnan Syed,” it’s unlikely your top hit would be a news story or Wikipedia entry about a criminal trial that resulted in a life sentence (plus 30 years) for the 1999 murder of Hae Min Lee, a former girlfriend.

It was a sad, grisly tale and trial, but not particularly well-known to those outside his family, friends and community. Syed became just one of the estimated 2.3 million Americans serving time in jail.

But that was before the award-winning and hugely popular podcast Serial began deconstructing the trial under a microscope. Host Sarah Keonig’s seeming obsession with the case had subscribers hooked.

“What the podcast did was get evidence that wasn’t there before,” said Laura Simpson, an attorney for the Volkov Law Group. Simpson also blogs for another podcast, Undisclosed, which dissects the case against Syed (It is produced by Rabia Chaudry, a close friend of the Syed family).

“I’m pretty sure the judge had not listened to the podcast. But the attention does bring forward information,” explained Simpson. “Without the podcast, I don’t know how that information would have come forward.”

In fact, it was Simpson who found the evidence on which Judge Martin Welch based his decision, which Keonig acknowledged in a blog post:

“This particular problem, by the way, was not brought to light because of Serial’s reporting. It was discovered by attorney Susan Simpson, working with the "Undisclosed" podcast started by Rabia Chaudry. She tracked down the cellphone expert who testified in Adnan’s trial, and found out he was unable to stand by his crucial trial testimony from back in 2000.”

A retrial in and of itself does not mean the original verdict was a mistake.

Shortly after the news broke, the Lee family stated very clearly it still believed their daughter was killed by Syed. And the prosecution says it will appeal the retrial ruling.

A very high legal bar

Aside from the extraordinary and unusual hyper-focus on Syed’s trial – two podcasts dedicated to sifting through every detail coupled with determined advocates - winning a retrial is no easy feat in the American judicial system.

“It is very difficult because it has to be an error that was so egregious that it would impact the ultimate outcome of the case. There are just very few cases that have that,” said Judd Legum, an editor for ThinkProgress and a former defense attorney. “And so the bar is set very high. I mean in this case, it took [Syed] 16 years to wind his way through all of this.”

There is also the passing of time. Memories fade and are less reliable. Key players sometimes die.

Even if a retrial is granted, prosecutors may have an impossible task in retrying a murder case.

“I think the judge was sending a message to the prosecution... that a case needs a timeline, and this timeline just doesn’t work,” said Legum, who makes the case in recent article that an actual retrial is very unlikely.

Simpson reads it the same way.

“There’s just nothing left,” she said. “They would have to start anew and I don’t know how they could possibly find a case to support that.”

Putting on a new trial is both financially and emotionally costly, she added.

There is an appeals process built into the American judicial system that Syed exhausted several years ago. Legum argues there may be a plea deal—or the case may be dropped altogether.

The larger point seems to be the existence of a certain deference to the original attorney—a cultural tendency to grant the prosecutor the benefit of the doubt no matter how flawed the case. And a mindfulness towards the victim's family and friends.

“There are errors like this that happen all the time - big cases, small cases – and most of them are not thrust out in this manner,” said Legum.

Even with clear prosecutorial misconduct, the American legal system is not designed to go back and correct those kinds of errors.

“It’s not a rarity to have a case where there is vital information about a defendant's culpability that’s either withheld or never uncovered because no one cares enough to dig it up,” according to Simpson.

“And I think it’s a much larger percentage than the system, as it is currently, wants to acknowledge.”