In 1950 Harvey Matthews remembers playing with friends in a cemetery across the street from their family farm outside Washington, D.C.

“I was a kid, I played in it. So now where did the bodies go? Can you tell me where did the remains go? No one has answered that question for me yet” he said.

For decades, stories about the black cemetery were mostly forgotten.

In the 1960s, construction of a high-rise and parking lot in Bethesda, Maryland, was thought to have covered part of the burial ground. Matthews says the workers bulldozed over African American remains, while wiping away a century-old community founded by free slaves after the Civil War.

“My dad had a farm area, we had horses, chickens, and hunting dogs that my dad trained for white people who lived around the area. My dad trained the dogs for them and pretty much that’s how we lived,” said Matthews, 73.

Now known as the Westbard neighborhood in Bethesda, the area is filled with shopping centers and high-priced homes. Plans for a multimillion-dollar development project have been put on hold pending an archaeological investigation to determine if the project is being built on top of the historically significant cemetery.

History of a forgotten community

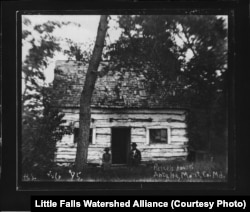

River Road was a popular trail, its history dating back to the Seneca Indian Trail. The rural land was owned by white plantation farmers. But by the end of the Civil War, land ownership changed.

“After the Civil War, several freed black slaves, [who] were probably from relatively close to that area, they started buying land and they appeared in the census decade after decade and built a whole community, which lasted about 100 years,” said Amy Rispin, local historian of the Little Falls Watershed Alliance (LFWA).

“By the turn of the [20th] century, the next generation was growing up and that’s where you start seeing vibrancy as well as new people entering in, and also businesses,” said Paige Whitley, another local historian of LFWA. “This is a time period of transportation bringing goods in, transportation setting up jobs, people there were taking advantage of those jobs.”

Developers, in the 1950s, began to buy parcels of land in the community.

“The developers started to build shopping centers, started to build additional residences in the area, and therefore started to purchase the land that was then still in the ownership of the African-Americans that were there,” said David Kathan, local historian of LFWA.

By the early 1960s, all of the African-American families had left River Road and the area transformed from a residential to a commercial area.

Hope for the future

The last-standing building of the former African-American neighborhood is the Macedonia Baptist Church. Its congregation and others in the community want a museum built nearby that details the history of the black community that once thrived here.

“Our main goal, and our No. 1 priority, is to get a museum built so we can show whoever, where [or] how far they come [from], they can go into this museum and learn the history of River Road that once was.” Matthews said.

“I named it, as, it’s like a lost colony that once was and now is gone. You see it, and now you don’t, that’s how it turned out to be. We’re struggling, we’re fighting the fight. We might lose a little, a few battles along the way, but our main goal is to win the war,” he added.

![After the Civil War, freed slaves bought land. By the turn of the [20th] century, the next generation was growing up and becoming members of the River Road African American community.](https://gdb.voanews.com/A3EF9F68-A09C-45AC-8A13-9AFB41F4107A_w250_r0_s.jpg)