Momentum is growing for congressional Democrats to challenge U.S. President Donald Trump’s declaration of a national emergency at the U.S.-Mexico border, in order to shift billions of dollars from defense to construction of a southern border wall.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California encouraged her caucus to support a resolution that Congressman Joaquin Castro, a Democrat from Texas, plans to file Friday that would attempt to reverse the president’s move. As of Tuesday night, 93 House members have pledged to support the bill. Many more will likely sign on in the coming days.

Pelosi said lawmakers would move quickly on the resolution, setting a timeline for a vote on the House floor by mid-March. Here are six things you should know about this historic controversy.

What is a national emergency?

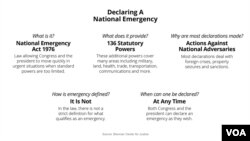

A declaration of a national emergency gives a president the power to temporarily address an urgent situation that the U.S. Congress may not have time to immediately react to.

The U.S. Constitution does not specifically address the issue of a president declaring a national emergency. The 1976 National Emergencies Act, however, grants a president the authority to make that move with limitations that prevent the emergency from continuing indefinitely. Congress has given the president that power 58 times since 1979, including 31 declared national emergencies that are still in effect. The others were eliminated through congressional action.

Previous national emergencies have been declared for natural disasters such as floods and hurricanes or in the case of the Sept. 11, 2011, terrorist attacks.

Why does the U.S. Congress have the final say on declaring a national emergency?

It’s all a matter of money and of power. The U.S. Constitution gives Congress “the power of the purse,” a phrase lawmakers often repeat to emphasize their crucial role in setting the budget for the United States and then specifying how money should be spent through appropriations legislation.

In the current controversy, Congress was willing to provide $1.37 billion in new funds for Trump’s proposed wall construction, while the president demanded nearly $6 billion. At that point, Trump declared an emergency.

Congressional oversight also prevents a president from unilaterally seizing power. National emergency declarations have no set definition or limits, making the move open to abuse. Past presidents have used emergencies to declare war and — in the case of President Franklin Roosevelt in 1942 — to intern thousands of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Has Congress ever reversed a national emergency?

Under that 1976 act, once the president acts, the Congress is supposed to meet to decide whether to continue the emergency or to terminate it. Lawmakers can vote at any time to terminate the emergency, requiring majorities of the House and the Senate.

If the House Democratic resolution to be introduced Friday passes both chambers of Congress and survives a veto, the president would not be able to move money already earmarked for Department of Defense projects to fund construction of sections of a wall at the U.S.-Mexico border. But Congress has never blocked presidential action this way before.

WATCH: Trump Emergency Decision Sets up Political, Legal Battle

Why do Democrats say the situation at the border isn’t a national emergency?

Trump for months has argued that he needs more than 300 additional kilometers (200 miles) of wall along the border to stanch the flow of illegal immigrants and drugs and halt human trafficking across the border.

Democrats disagree with that assessment. They argue that appropriators — the members of Congress who decide how federal money is spent — reached an agreement on border security spending that the president then signed into law, ending the threat of another government shutdown Feb. 15.

They point to declining numbers of illegal immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border as well as the president’s failure to act legislatively when the Republican Party controlled both chambers of Congress for the first two years of his presidency.

Additionally, the president undercut his own case when he seemingly acknowledged that the “emergency” was not urgent.

“I didn’t need to do this,” Trump said in his Rose Garden press conference announcing the move. “I just want to do it faster.”

However, there are laws enacted by Congress allowing a president to move funds around when an emergency is declared. This statute says the president can “undertake military construction projects, not otherwise authorized by law that are necessary to support such use of the armed forces.”

Can it be reversed in courts instead?

This is also a possibility. Sixteen states, led by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, have filed a lawsuit alleging the president’s move is unconstitutional. President Trump anticipated this move when announcing the emergency, predicting the lawsuit would move through U.S. courts all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

There is some precedent for the Supreme Court to overturn a presidential move on the basis of an emergency. The court ruled 6-3 against President Harry Truman for his 1952 move seizing control of U.S. steel factories during the Korean War. But Truman’s seizure of the factories was made under his constitutional powers, not under the basis of an emergency.

The current lawsuit’s movement through the U.S. court system would take time while a congressional resolution would move relatively quickly.

What are the chances of passage?

The resolution will almost certainly pass the Democratic-majority U.S. House. But it faces a much tougher road to passage in the Senate, where the Republicans hold a 53-47 seat majority. The Democrats must enlist the support of at least four Republicans in order to win passage in the Senate. Even if the measure somehow wins passage in the Senate, proponents would have to muster a two-thirds majority to override Trump’s almost certain veto.

Still, some Republican senators expressed grave concerns about Trump’s use of the emergency declaration.

“We have a crisis at our southern border, but no crisis justifies violating the Constitution,” said Senator Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican.