A U.S. Senate subcommittee has issued a new report highlighting four egregious cases of African countries trying to funnel millions of dollars into the United States to buy expensive houses and luxury goods. The purpose of the country case histories, all of which have been documented elsewhere, is to set the stage at congressional hearings which opened Thursday on crafting new legislation.

The bill, to be drafted by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, is intended to curb the use of American institutions by corrupt foreign officials who have stolen their countries’ wealth and denied their citizens of vital resources for health, education, and the alleviation of poverty.

Arvind Ganesan, the business and human rights director for Human Rights Watch, says that the Senate subcommittee, overseen by chairman Carl Levin of Michigan and ranking Republican Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, has the potential to make major changes that would stop American lawyers, realtors, banks, and universities from accepting funds that would aid corrupt rulers.

“It’s a much worse situation if there are no laws or regulations in place. And in this case, the whole issue of realtors is a major loophole. And so you can reasonably assume that as long as it’s not illegal, somebody will do it. So the best thing you can do is make it illegal, and when people are caught doing something illegal, they’ll be held accountable,” said Ganesan.

Ranking minority subcommittee member Senator Coburn said at Thursday’s hearing that despite some unspecified reservations, he would like to support legislation being prepared by Senator Levin. Ganesan says the law could be introduced in conjunction with an earlier proposal on banking secrecy and offshore tax havens prepared by Levin and then-Senator Barack Obama.

“This could move relatively quickly, and I think the hearings showed how scandalous the situation really is, when people can bring literally tens of millions of dollars of stolen money into the country and buy luxury items all over the place,” he observed.

Three of the four case history African countries, Nigeria, Angola, and Equatorial Guinea, are among the largest oil producers in sub-Saharan Africa, and two, Algeria and Nigeria are members of OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Gabon left the cartel in 1995, while the other three are major oil exporters to the United States.

In the example of Angola, the subcommittee report considered a fraudulent $50 million central bank diversion scheme by Dr. Aguinaldo Jaime, Angola’s former central bank governor and deputy prime minister. Human Rights Watch’s Ganesan says it almost succeeded, but ultimately did not get carried out.

“He tried in June of 2002 to transfer money from the central bank The bank in the U.S. thought it was suspicious and returned the money. Then, about two months later, in August, 2002, he tried the same thing again in conjunction with a couple of individuals, and again, the bank thought it was suspicious. And in this case, the issue was actually prevented in many ways because two U.S. banks, Citibank and Bank of America, had real issues with it. In fact it led to Citibank closing down its office in Angola,” he said.

Despite what he calls “this minor success story,” Ganesan says it shows that tougher legislation could have discouraged such a situation from ever occurring. A January 2004 Human Rights Watch report, which the group says supports much of the Senate report’s findings, says that between 1997 and 2002, the Angolan government failed to justify $4.2 billion in spending, an amount that almost matched all of the social and humanitarian spending the country performed during the same period.

Investigators have known for many years about Equatorial Guinea President Teodoro Obiang Nguema’s efforts to pump huge sums into the now-defunct Riggs Bank of Washington, D.C. And the American public has received ample news media coverage of mansions, cars, a $38.5 million presidential jet and other extravagances pursued by Obiang and his family with funds from his impoverished country.

“In the case of Obiang, one of the things the hearings pointed out is that lawyers actively tried to help them circumvent those laws. So I think there has to be more rigor on what lawyers and other associates of people like Obiang and his son are doing. Secondly, the hearings identified a major loophole in the law that needs to be fixed, which is that a lot of corrupt officials like to buy mansions and big houses, and yet there’s no obligation on behalf of realtors or people like that to identify where the money is coming from. And so there should be some change in the law to make sure that they know their customer and do better due diligence in their dealing with these people,” he recommended.

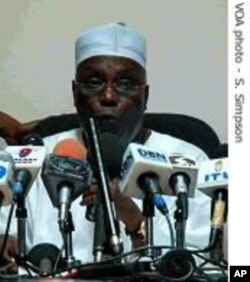

In addition, Ganesan called for stronger professional standards so that a situation like Nigeria’s former Vice President Atiku Abubakar engineered to transfer $14 million to Washington, D.C.’s American University would not occur again.

Mr. Abubakar and his wife succeeded in bringing $40 million in suspect funds into the United States between 2000 and 2008, $14 million of which were accepted by American University. In accepting the money, the Washington school did not question the source of the offshore corporations that transferred the funds in return for consultations by the college to help Mr. Abubakar set up a university in Nigeria.

“With the case of American University and others, it is also critically important, even in the absence of legislation, that universities, realtors, and other institutions do an adequate amount of due diligence, because even if it’s not illegal, if this information comes out, it’s certainly not acceptable to most of the public. And it would certainly be eye-opening to the people of Nigeria, who haven’t seen their living standards increased necessarily, that the money and the wealth of their country is ending up in a U.S. university,” Ganesan explained.

Supporters of the new legislation are hoping that it will plug several loopholes that were revealed in Thursday’s hearing and lead to more rigorous U.S. government enforcement efforts. Arvind Ganesan recommends another tactic he hopes will prompt U.S. consular services to deny visas to foreign rulers suspected of diverting and laundering funds, a tool that he says should be used more often to prevent the sale of mansions to people implicated with “abusing the wealth of their nation for personal gain.”