A resolution condemning white supremacists, neo-Nazis and other hate groups has been approved by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Donald Trump, who faced criticism over his response to violence that erupted at a white nationalist rally last month in Charlottesville, Virginia.

A 32-year-old woman, Heather Heyer, was killed and 19 others were injured when a car allegedly driven by a white supremacist slammed into a crowd. Two state police officers who were observing the protests were killed in a helicopter crash.

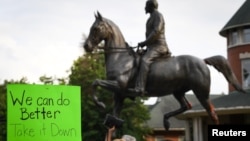

The protest, over plans to remove a statue of a Confederate general, has led to renewed debate in many U.S. states on whether to get rid of Civil War monuments that to some symbolize pride and part of American history, but to others are a festering symbol of racism.

WATCH: Passions Run High on all Sides as US Monuments are Removed

‘Facing the reality’

Independent historian Kevin Levin, who spoke with VOA via Skype, had this view: “I think more people are looking at those monuments and memorials and sort of facing the reality for which they were willing to give their lives, and that was the creation of an independent slave-holding nation.”

Ernie Williams, a Virginia resident, said of the monuments, “Everybody’s wanting to take them down. I don’t see why. It is not racial. There is nothing racial about it. It was a civil war.”

“It’s important to keep in mind the act of memorializing itself involved erasing history, so when you are looking at these Confederate monuments, sure they celebrate a very narrow understanding in many cases a very distorted, mythologized understanding of the past, but there’s also a lot of that history that’s pushed aside entirely,” Levin added.

In the end, it is up to communities as a whole to decide what they would like to do with the monuments, Levin said.

“At the time when most of them went up, roughly between 1890 and 1940, we are talking pretty much only the white community in many of these southern towns and cities were involved,” he said. “So in 2017, it’s perfectly appropriate that these questions on whether the monuments should be removed or relocated should also be decided by the local community.”

Arguments on both sides

Virginia attorney Barry Proctor said of the issue, “What I would hate to see is a knee-jerk reaction to a topic that needs to be discussed at length. It’s a question [of] are we remembering our history or are we memorializing a cause which would have been human slavery and states’ rights.”

While the debate continues, passions run high on all sides.

Washington, D.C., is home to dozens of monuments to the nation’s wars and those who fought them. Millions of people visit the capital city each year to visit these museums and memorials. On a recent day, several people in the downtown area had this to say about the issue of removing Confederate monuments.

“Generally, I think Confederate statues should be taken down,” Bruce Andersen told VOA. “I think the victors get to write history and the Union won the war. So as American citizens, all these rebels should be relegated to the dustbin of history.”

Thomas Arzu feels differently.

“It’s history and it needs to stay as a reminder of the atrocities that have taken place in the past. If you take the statues down, the younger generation will not have any concept or understanding of what it represented,” he said.

For Loretta Turner, the issue is not really about whether the monuments should stay or go but, “it really is about what is it that drives us to the racial behavior that makes us hate other people who are not like us. So once we get to the heart of that, I think we can resolve the issue because changing the monuments, taking them down or putting them up is not going to change who you are inside,” she said.

US monuments

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks U.S. hate groups, a recent study identifies about 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy across the United States, including 718 monuments and statues.

Last week, Washington’s National Cathedral removed stained-glass windows that depicted Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

“We have been looking at the reality of the windows and doing the larger work of trying to deal with the issues that lie at the heart of many of these monuments, which is the issue of race and slavery, the legacy of slavery in our country and racial reconciliation,” the Rev. Randolph Hollerith, dean of the Cathedral, said.

Hollerith said the process started two years ago after the massacre at a black church in Charleston, South Carolina, where nine people died at the hands of white supremacist Dylann Roof.

“The recent events in Charlottesville have changed the discussion in some ways and we can’t help but be responsive to those events going on as well,” Hollerith added.

Some say, however, that removing the monuments is like “erasing history.”

In the wake of the Charlottesville riot, President Trump made divisive remarks, which drew criticism from bipartisan lawmakers, business leaders and his own advisers.

On Thursday, Trump reiterated those remarks, telling reporters aboard Air Force One that he told Senator Tim Scott, a Republican from South Carolina, in a one-on-one meeting that “you have some pretty bad dudes” opposing white nationalists.

Trump invited Scott, the only African-American Republican in the Senate, to the meeting Wednesday in what the White House reportedly called a demonstration of his commitment to positive race relations.

Trump said he told Scott that violence by some in the so-called antifa movement — far-left groups that oppose white nationalists — justified his remarks condemning “both sides” for the Charlottesville violence.

Later Thursday, the White House released a statement saying the president had signed a resolution that condemned white supremacists, neo-Nazis and other hate groups, and urged his administration to speak out against such groups.