The head of a new commission formed to expose the truth behind human rights abuses committed during Colombia's long civil war has said it will focus on society's "most fragile" and look at why sexual violence against women was so prominent.

The 11-member truth commission, part of a 2016 peace deal between the government and Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels, started work this month and will convene hearings on select incidents of violence.

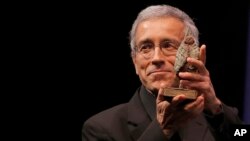

It is headed by Francisco de Roux, a 74-year-old Jesuit priest who has spent most of his life promoting peace efforts among warring factions and helping rural communities caught in the crossfire.

"We have been asked to focus on the most fragile of victims — women, children, old people, indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups, and LGBT people," he told Reuters in an interview.

"We want to establish what were the main patterns behind the biggest human rights violations ... the patterns that explain why women were raped, why land was stolen, why mass displacement occurred, why people were forcibly disappeared, why 30,000 people were kidnapped."

More than 220,000 people have been killed during the Andean country's conflict between the government, leftist rebels, right-wing paramilitaries and drug traffickers.

There are an estimated 8 million war victims, 7 million of whom are displaced. One Marxist guerrilla group and myriad crime gangs remain active.

Some of the worst violence was inflicted on women, and de Roux said the commission would investigate why.

"Most probably we will find that how women were treated in such a violent way [was down to] the macho and patriarchal culture, which is something deep inside of us that treats women as inferior human beings," de Roux said.

Healing wounds

Authorities have said the government-funded commission, which includes a philosopher, an indigenous lawyer and an economist, will not be able to hear about every injustice because there are too many, but it will help to heal wounds.

Over the next three years, it will hold public hearings across Colombia and collect testimony from victims and perpetrators.

Its remit does not include prosecution, and de Roux said it would be difficult to establish a consensus on what caused the violence in a society still deeply divided.

"There will be many hypotheses to explain the problem of violence and often we will not be able to reach an objective truth," he said.

"Truth is more of an intention that human beings have to reach reality but we often fail to achieve it. What we get are hypotheses that, at best, can answer pertinent questions."

Instead, Colombia's Special Jurisdiction for Peace tribunal, set up earlier this year, will try FARC leaders and military officials for war crimes.

Indifference

One of the challenges the commission faces is the widespread indifference of Colombians to the suffering inflicted during the 52-year conflict, de Roux said.

"One of the problems we have to clarify is why the conflict led us to a very deep indifference," de Roux said, citing levels of "social and cultural trauma" that have led to problems being ignored as a survival mechanism.

Experts say truth commissions in other parts of Latin America, from Guatemala and El Salvador to Argentina, have only offered a limited version of the truth and a starting point from which to heal the wounds of war.

"I think that some Colombians are ready to hear the truth, while others aren't," de Roux said.

"But we don't have a choice. I'm convinced that the truth is vital. It's absolutely necessary if we want to build a different kind of country."