It was a thrilling find for a then-graduate student in linguistics: While conducting research in Jesuit archives in Quebec in 1999, Michael McCafferty discovered a previously unknown manuscript - a dictionary of the Myaamia-Illinois language, handwritten by a 17th century Jesuit missionary.

Comprising some 22,000 entries, the manuscript has played a key role in helping the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma revitalize a language not spoken in generations.

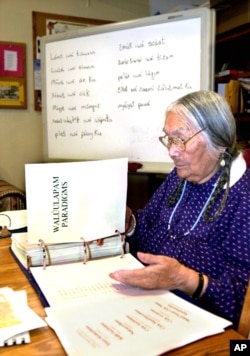

In Massachusetts, linguist Jessie Little Doe Baird, a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe in Massachusetts and co-founder of the Wopanaak Language Reclamation Project, is also working from old documents to restore a language that died out a century ago.

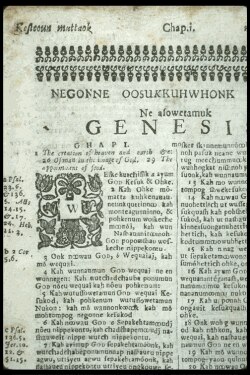

“We have the largest collection of Native-written documents in North America,” she said, explaining that 17th century missionaries worked with the tribe to create an alphabet and translate the Bible and other works.

“The Wampanoag people quickly took the convention of writing and used it as a tool to protect themselves where land transactions and other things were concerned,” Baird said. “We’ve been plugging away at this for about 25 years and now have a dictionary with roughly 12,000 entries, compiled just from those early documents.”

Today, the tribe boasts two credentialed linguists and a Wopanaak immersion school for preschool through first grades, which Baird hopes will expand in the future.

'Little gossip'

Restoring a language is one thing. Ensuring its survival depends on being able to teach it so that it can be passed on to the next generation. And that means making the language relevant to youth today by coining new words and phrases.

Tribes approach the challenge in different ways.

The Wampanoag pretty much do what English speakers do,” said Baird. “Communities borrow words, and if somebody at some point decides that something is important, they will give it a name in that language.”

Some tribes would rather not borrow, said James Andrew Cowell, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of Colorado who is working to preserve Arapaho, an Algonquian language native to the Great Plains.

“I think this kind of approach preserves their particular perspective on an item, and that way, they feel that their culture and their meaning systems are still present in the language,” Cowell said.

He gives some examples.

“The word for computer translates as, ‘It knows everything,'” he said. “In Arapaho, there is a way to turn verbs into nouns. So, I am typing on the 'It knows everything' means ‘I am typing on the computer.’”

Some words reflect a sense of humor.

“The word the Arapaho have coined for Facebook is ‘gossip,’ and for Twitter, ‘little gossip,’” he laughed.“And sometimes, new terms offer oblique commentaries on European/American culture. The word for ‘rice,’ for example, is ‘maggots.’”

Community effort

Coining neologisms is nothing new to tribes, said Ben Black Bear, Sicangu Lakota and founder of the Lakota Studies Department at Sinte Gleska University on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota.

“Back in the early 1900s when they first established the reservation, we Lakota had to create words for all kinds of new things we had never seen until the Europeans came — wooden houses, clothing, the automobile,” he said.

Often, they did so by describing an item’s attributes.

“The apple did not exist in nature before we met the Europeans, so we had to create a word," Black Bear said. "When you bite into an apple, the inside is sort of like wet snow. So, we combined the words for wet snow (spanla) and fruit that has skin (tha) to come up with a new term, 'thaspan.'"

Another example: Lakota men traditionally wore leggings and a breech or loincloth.

“When pants or overalls came along,” Black Bear laughed, “we came up with ‘something that covers the rear end.’"

Today, Black Bear and other Lakota linguists meet annually at the Lakota Language Consortium’s (LCC) summer language institute, designed to teach Lakota teachers.In addition to taking a course in developing neologisms, they debate and approve new words just as their ancestors did. “Once we come up with a new term, we put out there for the community,” he said. “If people like them, they’ll use them.It’s not up to us.”

To see Black Bear and participants debating word options in video below:

Funding challenges

Once, Native Americans and Alaska Natives across America spoke as many as 300 languages.But centuries of conflict, forced relocation and forced assimilation caused half of them to go extinct. Whether those languages that survive can survive depends on continued funding from the government and private donors.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Languages Act, acknowledging U.S. responsibility to help tribes recover and preserve their language, and offers funding through a variety of programs. But tribes complain that funding is uneven and insufficient to meet their needs.

This week, the National Endowment for the Humanities, in conjunction with the First Nations Development Institute, announced grants to support language revitalization efforts in 13 tribes across the country.

Among them, the Wampanoag in Massachusetts will receive $90,000 to help expand their language immersion school another three grade levels.