As climate talks wind down in Paris, new space-based tools are gearing up to curb greenhouse gases, and to understand what happens to carbon dioxide after it is emitted.

One tool will help monitor deforestation and help enforce agreements to stop it. The other gives scientists the most detailed information ever on where carbon dioxide is coming from and where it is going.

Deforestation accounts for between 10 and 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The draft Paris agreement backs programs that give financial rewards to successful efforts to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, programs known as REDD.

For those programs to work, "we need to know two things," said Scott Goetz, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center. "We need to know how much carbon is in the forest and we need to know where the forests are being degraded," or lost.

3-D view

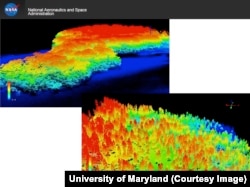

Satellite imagery is already used to monitor and curtail deforestation in places like Brazil. But those images only capture the forest canopy. A new instrument will map the forest in three dimensions.

"It tells you how dense the canopy is and how complex it is," Goetz said. "The more complex, the higher the biomass is of the forest. Half of biomass is carbon."

The instrument is called a Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) Lidar. It produces imagery using reflected laser light, the same way radar measures reflections of radio waves. It is slated for deployment on the International Space Station in early 2018.

At the Paris climate conference, Goetz released a new study showing that the tools to make REDD work are available now, or soon will be.

"The ability to measure and monitor emissions from deforestation is not a limitation to the implementation of REDD," he said.

Watching carbon move

Forests and oceans absorb about half of the carbon dioxide that human activities emit, according to NASA atmospheric scientist Lesley Ott.

"That's really important because if we didn't have that help from the land and the oceans, we'd see carbon dioxide building up in the atmosphere more rapidly and climate change progressing more quickly," she said.

But scientists don't know exactly where and how that carbon dioxide is absorbed, or how much — or why — that absorption varies from year to year.

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory, or OCO-2, will help get a handle on those unknowns.

The satellite-based instrument lets scientists visualize on a global scale where carbon dioxide is emitted and where it is taken up.

In the first year of data collection, Ott and colleagues were able to watch plants in the northern hemisphere suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere in the early spring.

"It happens over the course of a few weeks to a month," she said. "That's really incredible. And that's really the first time we've been able to observe those kinds of processes in that kind of detail."

The satellite is not designed to monitor greenhouse gases with an eye toward enforcement the way GEDI does, but, Ott added, OCO-2 is "giving us a tantalizing view of what satellites could do."