Even in the age of the Internet and DVDs, classical theater is flourishing in New York.

Some of the plays in the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s 2011 classical theater season are over 400 years old but ticket sales have been brisk. Joe Melillo, BAM’s executive producer, says theatergoers are hungry for a diet of Ibsen, Gogol and Shakespeare.

"They’re flying, they have, like, little wings," he says. "The tickets are flying out of the box office."

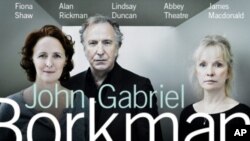

The artists presenting the plays say that’s because they resonate with contemporary audiences. Take "John Gabriel Borkman," playwright Henrik Ibsen’s 1896 drama in which the title character, a banker, has been imprisoned for illegally investing his client's money. Ibsen could have been writing about financier Bernie Madoff, now serving a 150-year prison sentence for orchestrating a decades-long swindle that took tens of billions of dollars from his unwitting investors.

"You see the byproduct of these legal battles that the families fall apart, because financial difficulties, or financial shame, produces a terrible fallout in families," says actress Fiona Shaw, who plays Borkman’s wife.

On an even more universal level, Ibsen’s three central characters are imprisoned by their own delusions and bitterness, says Alan Rickman, who plays Borkman, and Lindsay Duncan, who plays the woman he abandoned.

"They’re just very exaggerated versions of people we all know," says Duncan.

Rickman agrees. "We all know them. We’ve all grown up with these people."

Delusional characters are also at the heart of BAM’s next presentation, an adaptation of Nikolai Gogol’s short story, "The Diary of a Madman." Academy and Tony Award-winner Geoffrey Rush stars. Even though Gogol wrote about a mid-level bureaucrat in 1835 Russia, Rush says it feels like modern absurdist writing.

"Gogol walks this very knife-edge, fine-line between a very sharp observation of someone’s descent into madness and, at the same time, playing fairly deliciously with their own sense of delusion."

If Rush’s character descends into madness, the same is true of Shakespeare’s "King Lear," which Derek Jacobi is bringing over from England. Director Michael Grandage observes that, while the play has large political dimensions, Shakespeare has tapped into something more primal.

"The center of the play is a great domestic drama and he clearly was a man who was writing with a huge degree of knowledge about the nature of an aging parent," says Grandage. "We have different words for it now - of course, in Shakespeare’s time it was called madness and it’s called madness throughout the play. But, for madness now, we have dementia."

And it’s these universal human experiences, which most people can identify with, that continually draw audiences and artists back to the classics.