For generations, the circus meant big entertainment – elephants, lion tamers, dancing bears, high-wire acts. But times, and tastes, have changed. In May, after nearly a century and a half, the Ringling Brothers/Barnum and Bailey Circus – “the greatest show on earth” – will close.

But circuses are alive and well, largely without the ringmasters and exotic animals. Instead, they use a combination of music, amazing acrobatics and story-telling to transfix their audiences.

“Circus artists have been producing new and incredible circus acts and apparatuses and shows that have an artistic context and theatrical storylines, or well-drawn characters," Adam Woolley notes. "And this has been happening around the world for the past 10, 15 years or so.”

Woolley runs Circus Now, a non-profit organization which supports and promotes contemporary circus arts, which combine traditional circus skills, like acrobatics, juggling and trapeze, with theatrical techniques to tell a story.

Cutting-edge entertainment

Here in the U.S., smaller traditional troupes, like the Kelly Miller Circus, still pitch their tents across the country. But Woolley says there are more experimental companies that are pushing the art form, and those are the ones Circus Now works with.

“Audiences or families who might not be interested to go see, you know, some very avant garde modern dance, will still go see the circus. You know, people who would prefer to watch movies or television than go see a play, will probably still come see the circus.”

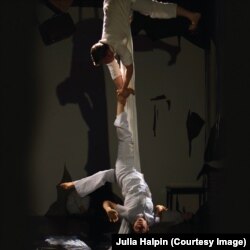

Circus Now's festival in New York this month featured the Race Horse Company from Finland. Acrobat Rauli Kosonen formed it with a couple of other performers nine years ago, because he says there’s something unique about circus.

“I think it’s really pure art form, in the sense that you can really feel the risks – there’s a lot of risks, so you can get a lot of adrenaline, while you watch it, if there is kind of tricks that make your heart bounce. Because it’s real. They can see if they make a mistake, they might get hurt. So, I guess that’s always been why circus is appealing. It reminds us that, uh, we’re humans.”

And Kosonen – whose specialty is trampoline - has the broken bones to prove it.

“Well, I had three operations," he admits, adding ruefully, "it’s part of the job; sometimes you don’t get lucky.”

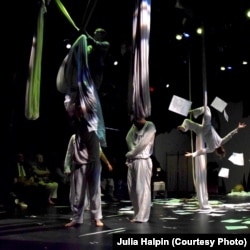

New York’s Only Child Aerial Theatre also performed during the festival. Kendall Ridleigh, one of the troupe's founders, says they shy away from calling themselves a circus.

"Just because there is the implication that the skills or the spectacle is sort of paramount, rather than the narrative. And we really have tried to keep the narrative the most important element and have the skills really drive and support the narrative.”

In a former factory in Brooklyn, Only Child is rehearsing its latest show, Asylum. It’s set in a mental institution in the 1970s. There’s a story, but there’s no spoken dialogue, says co-founder Nicki Miller.

“We would describe it as a theater piece that includes a lot of aerial work, dance, some recorded music, some live music and overhead projection and shadow. So, the story is told, rather than through dialogue, through the conversation of those theatrical vocabularies, instead,” Miller said.

So, even as the performers do aerial tricks, they’re dressed like mental patients, doctors and nurses, says Rileigh. There are no sparkles or spandex. But, they’re still doing stuff high off the ground...without a net.

A big tent for big stories

Circus Now’s Adam Woolley says contemporary circus companies, even with their different skill sets and artistic approaches, all fall under what can only be called the "big tent" of what circus can be.

He says they share the belief that with lots of practice and hard work, they can accomplish the impossible.

"That’s the core idea that everyone in circus believes in and everyone in circus tries to impart to the audiences - that 'I have dedicated my life to this seven minutes of performance and honed my skill to the place where I’m going to accomplish something in front of you now that you did not think could be done.’”

And that’s what still thrills audiences.