Bao Tong, a top official turned leading critic of the Chinese Communist Party, is being mourned from afar this week by his closest friends and supporters, many of whom were barred from attending his funeral on Tuesday.

"Elderly Bao," who died in Beijing on November 9 at age 90, "was essentially our spiritual leader," Gao Yu, an independent commentator in Beijing, told VOA's Mandarin Service, on social media upon news of Bao's passing.

Gao recalled many meals organized over the years by dissidents in Beijing where a "keynote speech" by Bao was always the highlight. Gao, a former journalist working for Chinese official media who herself was jailed multiple times, was among those whom Chinese authorities prevented from attending the funeral.

Bao, born in Zhejiang province near Shanghai in 1932, joined the Communist Party in the 1940s and rose through its ranks, reaching the position of chief adviser to Premier Zhao Ziyang, who spearheaded a series of economic and political reforms in the 1980s.

Both men were ousted from the government in 1989 for being seen as sympathetic to nationwide protesters whose demands for democracy culminated in the Tiananmen Square massacre. Bao served a seven-year jail term followed by one year in a halfway house.

While still under heavy surveillance in 1998, Bao gave an interview to Scott Pelley of CBS News around the time of a visit to China by then-U.S. President Bill Clinton. Pelley, whose career with the American network includes years as the "CBS Evening News" anchor and now as a senior correspondent for "60 Minutes," devoted a chapter to Bao in a 2019 memoir titled "Truth Worth Telling."

"He was willing to risk his freedom to speak for freedom," Pelley wrote of Bao, who stepped out of his apartment to be interviewed in a public park. The newsman recalled Bao's answer when he was asked what Americans should understand about "the struggle" in China.

"If people can check and balance the power of the government, then the government can become a force that safeguards world peace," Bao replied. "Otherwise, it is a dangerous force."

"As he and I parted," Pelley wrote in his memoir, "neither of us could foresee the relentless trampling of the tender shoots of freedom" in the years that followed.

Reflecting on the dissident's death in an exchange of emails with VOA, Pelley said, "Bao Tong loved his country and his people. That's why he took so many personal risks for justice and freedom. The fact that the Communist Party worked to suppress him is testament to his powerful ideals."

Over the past two decades, although Bao could not be seen or heard on Chinese official media, he managed to share his views with his fellow Chinese through a column for Radio Free Asia and multiple interviews with VOA's Mandarin Service, Radio France International and Deutsche Welle, among others. However, in a sign of tightened control in Beijing, reporters who had interviewed him in the past were not able to reach him this past year.

Four days before his passing, Bao celebrated his 90th birthday and made the following comment, which his daughter, Bao Jian, recorded: "A man is but a tiny, momentary existence between heaven and earth. You, my friends, have not abandoned me, all these years, and I, have kept you in my thoughts. It doesn’t matter much what age I am, what matters is the future we ought to fight for, what matters is the present day we must fight for; we ought to do what we are able to, and must, do today, and do our best to do it well."

Bao Tong is also survived by a son, Bao Pu. His wife of over 60 years, Jiang Zongcao, passed away in August. Both their children, whose given names refer to simplicity and earnestness, appear to have inherited their father's commitment to openness.

Bao Pu heads the New Century publishing house in Hong Kong and has put out volumes that mainland Chinese publishers can't touch, such as political histories and the memoirs of top officials. He often speaks up about the shrinking civil space in Hong Kong.

Daughter Bao Jian pinned to her Twitter feed a VOA story about how the Australian government in April 2020 called for an independent investigation into the origin of COVID-19. "How do we answer to Chinese people and people of the world if we do not get to the bottom of what caused the virus that has led to such misery?" she wrote.

Bao Pu told VOA this week, "My father saw no conflict between traditional Chinese values and modern humanism in the West. He saw, instead, their essential commonalities, that they are both for the realization of the value of a human life."

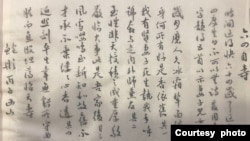

Bao Tong, like several of the fiercest advocates of democracy in China, was a huge fan of Chinese classics, as well as a self-taught student of English. Some of the poems he composed for his family and friends, and wrote in traditional ink brush, can be seen on a website set up this week in his memory.

One of the poems was written in 1996, while Bao Tong was being held in a halfway house in a Beijing suburb after being released from Qincheng prison, known for holding high-profile political prisoners.

"Years one has had to endure have been long. Ice and frost have carved out wrinkles on the face. What does one possess, after all? An everlasting fragrant scent [decency]," Bao Tong wrote.

Wei Jingsheng, a pro-democracy activist who spent a total of 18 years behind bars for "counterrevolutionary" activities, now lives in exile in the United States.

In a phone interview with VOA this week, Wei said: "At a time when China desperately needs men like Bao Tong, who understood and appreciated both Chinese and Western cultures and found in both sources to democratize and truly rejuvenate Chinese society, his passing is an immeasurable loss."

Wei urged observers from outside China to note that there are many Chinese who wish China to democratize, including some within the Communist Party, such as Bao Tong and Zhao Ziyang. "The fact that these individuals are not running the show today does not mean they don't exist," he said.

VOA's Mandarin Service contributed to this report.