In a surprise move Tuesday, China’s central bank let the country’s tightly-controlled Chinese currency, or yuan, see its biggest one-day drop in two decades. Analysts say the slide highlights growing strains in the world’s second largest economy, and there are concerns that such a dramatic one-off move could spark a currency war.

The value of the Chinese yuan has been gradually rising for a decade, and Tuesday’s fall was its biggest slide since 1994.

The 1.9 percent slide of the yuan against the dollar, just shy of its daily up or down limit of two percent, comes just days after China announced that exports had once again fallen, contracting more than eight percent from the previous year in July.

The fact that exports have been consistently down in the first half of the year is not the only factor, analysts said. The recent volatility in the country’s stock market, which is likely to have an impact on the country’s already slowing economy in the second half of the year, also played a role.

Breathing room

But aside from China’s broader economic challenges, the currencies of most of the major countries that China does trade with have been weakening, even as the yuan has remained relatively steady.

Analysts note that while the Chinese yuan has remained largely stable against the U.S. dollar for a year now, other currencies such as the Euro and Japanese Yen have weakened, putting pressure on the currency and hurting exports.

“If we look at the real effective exchange rate, which is against a basket of currencies that compose China’s major trade partners, it has appreciated somewhere in the range of 13 percent,” said Brian Jackson, senior economist at IHS Economics’ China Regional Service in Beijing. “So what that’s meant is that over the past year, exports from China to other countries besides the United States have become 13 percent more expensive.”

Reform measure

The People’s Bank of China has said the sharp one-day decline in the value of the yuan was aimed at making the currency more market oriented. It has focused less on the economic pressures that have coincided with the move.

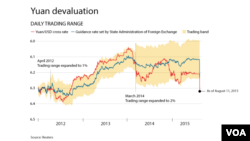

In the past, China would set a midpoint for trading each day based on a basket of currency rates. From that that point, the market could go up or down at least two percent. But in many cases, it would intervene if it felt necessary.

Now, the daily fix for the trading band will be based on a basket of major currencies and where the yuan closed in the previous trading session.

Brian Jackson at IHS Economics said the move could be a gradual step toward transparency, but much depends on what happens next.

“Really what we’ll have to see is whether or not they continue to see one-off depreciations at coincidental times or if this really was just a one-time devaluation,” he said.

Unlike most currencies, China’s yuan is not fully convertible, or freely traded on the international open exchange market. But Beijing has been working to internationalize its currency in recent years.

Liao Qun, chief economist at China CITIC Bank International, says the move is a step in the right direction toward the liberalization of the Chinese currency.

“Since the renminbi [the name in Chinese for the yuan] is still not freely traded, the People’s Bank of China will continue to intervene, but perhaps given the new announcement and reforms, the degree to which they will intervene will be much less frequent,” he said.

Currency wars

But despite Beijing’s portrayal of the move as a step toward reform, some analysts have warned that the sudden slide could have a ripple effect and that other countries could respond by weakening their currencies as well in a bid to maintain their competitive edge.

Liao Qun said that despite what some may think, the currency war has already going on for quite some time and Beijing’s move, if anything is just a response.

“The currency war has already had a huge impact on China and its exports… so it’s not China that is the one triggering a currency war,” he said.

SDR basket

Jackson adds that while the devaluation of the yuan will help exporters, a currency war is not something China would want from an economic perspective because it also imports a good percentage of the products that it eventually exports.

He says that it also doesn’t make sense given China’s persistent efforts to have its currency included as part of the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights, a reserve asset of currencies that now includes the dollar, Euro, Japanese Yen and British pound.

“If it becomes persistent and obvious that they are [China] getting back into the game of heavily manipulating the exchange rate, then that will surely affect their chances of getting into that [currency] group,” he said.

Earlier this month, an IMF staff report recommended the delay of any decision by the International Monetary Fund to add the yuan to its Special Drawing Rights currency basket. The report recommended that the decision be put off until some time in 2016.

But that decision hinges on whether the yuan is “freely usable” or not, the report said.