China pledged $23 billion in loans and aid to Middle Eastern countries last year and signed another $28 billion in investment for infrastructure and construction projects. As Chinese influence and business spread across the region, however, U.S. officials, suspicious of Chinese geostrategic intentions, are becoming increasingly wary.

They have urged Israel to reverse a deal giving a Chinese firm operational control of the port at Haifa, where American warships frequently dock. Last month, U.S. President Donald Trump urged Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu to curb his country’s warming bilateral ties with China, cautioning that otherwise U.S.-Israeli relations could suffer, according to American and Israeli officials.

Earlier in the year, John Bolton, U.S. national security advisor, also raised Washington’s worries with Netanyahu — and not just about Chinese management of the port at Haifa but also regarding Israeli use of Chinese telecom technology, which they fear will be used for spying and data gathering.

The Jerusalem Post has reported the U.S. Navy is considering switching its use of the port once the Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG) — a firm in which the Chinese government has high stakes — officially takes over in 2021. SIPG has been granted the port’s management for 25 years and has committed to invest $2 billion to transform it.

And U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, on a visit to Israel, told his hosts “intelligence sharing might have to be reduced.” He broadened out his warning about Chinese investment to other Middle East nations, saying, “We want to make sure that countries understand this and know the risks,” he said.

The bulk of Chinese investment in the region is tied to Beijing’s global trade and infrastructure program, informally known as the New Silk Road and formally as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a scheme launched in 2015 to spur trade along land and sea routes linking Asia, Africa and the Mediterranean.

A trillion-dollar trade, investment and infrastructure project, the BRI is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy project and China has already invested or loaned nearly $700 billion in more than 60 countries.

Critics say the enormous investment project can easily be leveraged for political and geostrategic influence and countries taking loans are likely to be caught in debt traps, hence Washington’s growing unease. China has signed the Belt and Road cooperation agreements with 17 Arab countries.

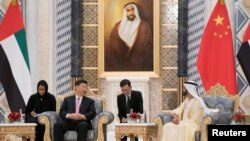

This week, dozens of heads of state will converge on Beijing for a Belt and Road Forum, the second major international conference on China’s initiative in under two years. But while the U.S. isn’t sending representatives, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi, the UAE’s prime minister, Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, and Djibouti’s President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, are all expected to attend.

Two years ago, China opened a military base in Djibouti, its first ever overseas base, positioned at a key maritime choke point, the strait of Bab al-Mandeb. The U.S. military already has a base there located just kilometers away. It has been used for operations against jihadist groups like Islamic State and al-Qaida. Some U.S. officials see China’s move into Djibouti as a sign of broader and possibly military ambitions.

Beijing maintains the BRI is only about greater connectivity and trade and can help solve major international challenges. China’s official news agency, Xinhua, says, “The initiative is a perfect example of China sharing its own wisdom and solutions for global growth and governance.”

But critics have noted that China is not shy about using trade and investment as a tool for statecraft and has in the past readily used commerce to extend its sphere of influence. U.S. policymakers fear that under the guise of the BRI, Beijing is also aiming to upset America’s traditional alliances. They question whether Beijing’s interests are purely economic.

Others see China's growing role in the region as mainly focused on securing energy resources and its thirst for oil. “In recent years, the region has been the source of as much as half of China’s imported oil. The BRI is expected to facilitate Chinese energy firms’ delivery of even larger volumes from the region,” according to Indonesian academic Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, writing for the U.S.-based Middle East Institute.

Karen Young of the American Enterprise Institute recently argued in a paper for the Washington-based research group that the Gulf Arab states have been eager to deepen ties with China, seeing it as its main “next-generation energy market” for oil and gas exports.

The relationship is unlikely to be frictionless, she says. Chinese and Arab interests could be at odds, too. She notes, “China is also a competitor in some areas where Arab Gulf states are investing in infrastructure, ports and political outreach to secure new security partnerships, particularly in the Horn of Africa.”

Meanwhile, while African and even European states have been ready to accept large Chinese loans for infrastructure projects, raising fears they will be caught in debt traps, which can then be used for political leverage by Beijing, Arab states, even cash-strapped ones, have been far more cautious about accepting loans. Algeria two years ago announced it wouldn’t enter major loans deals with the Chinese.