China continues to tighten its control over online speech and the internet environment as the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) prepares to implement a new set of regulations Monday to restrain the country’s fast-growing mobile apps.

Analysts say the new measures are in line with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s media policies and earlier calls for local media to serve the ruling Communist party’s interests, but at odds with the top leader’s vow in December that the country’s internet users must be free to speak their mind.

“The overall control (of freedom of expression) will continue and get harsher. The worst is yet to come, which we may see in the next couple of years. But it’s another story whether such a control will be effective,” said Qiao Mu, a professor at Beijing Foreign Studies University.

Authorities in China will keep a close tab on sensitive speech online to clear the way for Xi to cement his grip on power ahead of next year’s 19th party congress, the professor added.

Control over mobile apps

The CAC’s latest regulations state that, beginning August 1, all mobile app providers in China must confirm the real identities of their users in the app’s back-end platform by using their registered phone numbers.

Local app operators, currently totaling four million, will also be required to create an information security and content censorship system to filter out illegal content while tracking user log information, which will be kept on file for at least 60 days.

The effort follows swiftly on the heels of the regulator’s crackdown on eight domestic online companies, including Sina Corp and Tencent Holdings, whose news portals on Sunday were ordered to stop original news reporting. By law, they can only carry news published by licensed news organizations.

As such, penalties will be imposed on these online companies because their violation has caused a serious negative influence, authorities in Beijing were quoted as saying on state media.

The pace of online media control, moreover, is expected to accelerate following the promotion of Xu Lin as head of the CAC, Qiao noted.

Late last month, Xu, formerly deputy director of CAC, was tapped to replace his predecessor, Lu Wei, in chairing the powerful internet control and regulatory body.

Xu is widely believed to be a trusted associate of Xi after he had worked closely with the president during Xi’s tenure as the party’s secretary of Shanghai.

“Xu Lin has replaced Lu Wei. One of his major responsibilities is to implement (internet) policies under the helm of the big boss (Xi). Therefore, a slew of solid action (of internet control) will surely follow,” Qiao said.

Liberal magazine targeted

While tightening its grip over the web and information industries, Xi has also shown less tolerance over liberals even if they are from within the party, the professor added, referring to the recent closure of Yanhuang Chunqiu, a leading liberal magazine in China.

Founded in 1991, the magazine is known for challenging party views on sensitive issues, such as political reform and the Cultural Revolution. With a circulation of about 200,000 copies, it has also been seen as a forum for more reform-minded officials.

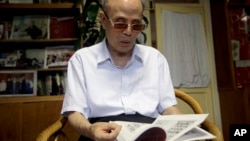

Shortly after its 25th anniversary, the magazine’s leadership, including its 92-year-old publisher, Du Daozheng, was reshuffled – a move critics say is a clear violation of press freedom.

Following the government-instigated management reshuffle, initiated by the Chinese National Academy of Arts, Du announced a halt to the magazine’s publication in a sign of defiance to the government’s censorship.

“The academy may be the one which openly pulled the plug on the magazine and led to its closure. But Xi Jinping was the man behind the scene, who has hoped that not only the media must serve for the party’s interests, but also any interpretation of Chinese history must conform to that of the party,” Gao Wenqian, a senior policy advisor at Human Rights in China, told VOA’s Mandarin Service.

The government, in addition, is said to be considering measures to exert a more direct form of influence over online media outlets, which include taking board seats or stakes of at least one percent in those companies.

But Qiao cast doubt on the government’s control over the Internet, saying the new media still provides plenty of leeway for millions of netizens to freely express themselves, which will exhaust the government’s efforts to stifle them.