Green energy is the new focus of China’s one-of-a-kind Belt and Road Initiative or BRI, that aims to build a series of infrastructure projects from Asia to Europe.

The eco-friendlier version of BRI has caught the attention of some 70 other countries that are getting new infrastructure from the Asian economic powerhouse in exchange for expanding trade.

The reset on China’s eight-year-old, $1.2 trillion effort comes after leaving a nagging layer of smog in parts of Eurasia, where those projects operate.

Now the county that’s already mindful of pollution at home is preparing a new BRI that will focus on greener projects, instead of pollution-generating coal-fired plants. It would still further China’s goal of widening trade routes in Eurasia through the initiative’s new ports, railways and power plants.

The Second Belt and Road announced in China on October 18, coincides with the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP26, which runs from Sunday through November 12 in Glasgow, Scotland. China could use the forum to detail its plans.

“China’s policy shift towards a more green BRI reflects China’s own commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2060 and its efforts to implement a green transition within China’s domestic economy,” said Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific chief economist with the market research firm IHS Markit.

“Furthermore, China’s policy shift…also reflects the increasing policy priority being given towards renewable energy and sustainable development policies by most of China’s BRI partner countries,” he said.

The Belt and Road helps lift the economies of developing countries from Kazakhstan to more modern ones, such as Portugal. BRI also unnerves China’s superpower rival, the United States, which has no comparable program.

History of focusing on fossil fuel

China has a history of putting billions of dollars in fossil fuel projects in other countries since 2013, the American research group Council on Foreign Relations says in a March 2021 study.

From 2014 to 2017, it says, about 90% of energy-sector loans by major Chinese banks to BRI countries were for fossil fuel projects and China was “involved in” 240 coal plants in just 2016. In 2018, the study adds, 40% of energy lending went to coal projects. Those investments, the group says, “promise to make climate change mitigation far more difficult.”

South and Southeast Asia are the main destinations for coal-fired projects at 80% of the total Belt and Road portfolio, the Beijing-based research center Global Environmental Institute says.

Global shift toward green energy

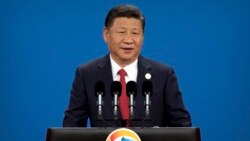

Chinese President Xi Jinping said last year China would try to peak its carbon dioxide emissions before 2030. The Second Belt and Road calls for working with partner countries on “energy transition” toward more wind, solar and biomass, the National Energy Administration and Shandong provincial government said in an October 18 statement.

Some countries are pushing China to offer greener projects due to environmental pressure at home, though some foreign leaders prefer the faster, cheaper, more polluting options to prove achievements while in office, said Jonathan Hillman, economics program senior fellow at the Center for International & Strategic Studies research organization.

“There was a period in the first phase of the Belt and Road where projects were being shoveled out the door and with not enough attention to the quality of those projects,” he said.

Poorer countries are pressured now to balance providing people basic needs against environmental issues, said Song Seng Wun, an economist in the private banking unit of Malaysian bank CIMB. The basics still “take priority,” he said, and newer coal-fired plants help.

“Although I would say environmental issues (are) important, I think a lot of people don’t realize how much more efficient these more modern coal plants are, so I think we must have a balance,” Song said.

In the past few years however, cancellation rates of coal-fired projects have exceeded new approvals, Hillman said. “The action honestly has come more from participating countries,” he said. “They’ve decided that’s not the direction they want to go.”

In February, Chinese officials told the Bangladesh Ministry of Finance they would no longer consider coal mining and coal-fired power stations. Greece, Kenya, Pakistan and Serbia have asked China to dial back on polluting projects, Hillman said.

“The next decade will show to what extent the Belt and Road will drive green infrastructure,” London-based policy institute Chatham House says in a September 2021 report.

Belt-and-Road renewable energy investments reached a new high last year of 57% of its total for energy projects in 2020, according to IHS data.

New pledges at COP26?

COP26 is expected to showcase the environmental achievements of participating countries as they try to meet U.N. Paris Climate Change commitments, Biswas said.

China’s statements ahead of the conference so far differ little from past statements. But China’s energy administration said on October 18 that its second Belt and Road “emphasizes the necessity of increased support for developing countries” in terms of money, technology and ability to carry out green energy projects.

Chinese companies on BRI projects may eventually be required to reduce environmental risks, Biswas said. Those companies would in turn follow principles released in 2018 to ensure that their projects generate less carbon. A year later, as international criticism grew, Chinese President Xi added a slate of Belt and Road mini-initiatives, including some that touched on green projects.

But the 2019 plans were non-binding and untransparent, Hillman said. At COP26, he said, “I would take any big announcements with more than a grain of salt.”