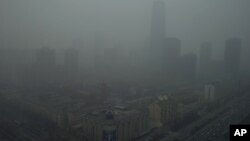

Unprecedented peaks in Beijing's chronic air pollution indexes have prompted unusually aggressive reporting from state media in the country. Media reports, which include calls for stronger government actions and questions about China's mode of development, show how people's concerns about the environment in China have reached a tipping point that neither the Chinese media nor the government can ignore.

Ever since monitoring stations started recording alarming levels of toxic matter in Beijing and other cities' air last week, news outlets have run updates and published editorials on the extent of the problem, and on the government's response.

Worth the risk?

Much media attention focused on the so-called “Chinese mode of development” and questions whether the economic achievements reached in the past few decades were worth the risk of compromising people's health.

The People's Daily, flagship publication of the Communist Party, ran an editorial on Monday titled “A Beautiful China Starts with Healthy Breathing.” The piece urged government departments to change their ways in how they deal with environmental problems.

“Economic development cannot follow the old path of 'pollution first, fix later,'” the article read. “Urban management cannot face emergency with the old mentality of 'bad air is just a small thing'.”

Xu Nan is the Beijing-based managing editor of the website China Dialogue, which tracks coverage and provides commentary on environmental issues in China. She says that she witnessed a shift in how environmental news is reported.

“In the past, the thinking was that environmental concerns might have an impact on the speed of development, so the emphasis was put on the protection of development over the environment,” Xu says. Now, she says, things have turned around.

“Environmental problems have now become something that cannot be ignored,” adds Xu.

She says that a string of environmental controversies in 2012 has showed the government that it cannot afford to disregard people's demands.

“In one case after the other, the government has recently been discovering that if they do not respond to public opinion, then that increases their cost in managing the situation,“ Xu says.

More media coverage

As protests against polluting projects gain boldness in China, media have increased their coverage of the events and the government has become more responsive.

In 2012, people protested against projects such as a coal-fired plant in Haimen, a wastewater pipeline in Qidong and a chemical plant in Ningbo. In many cases, public demonstrations brought a delay in the development of the project and sometimes even halted it.

Part of the government response in facing environmental issues has been to allow less strict disclosure of relevant information.

Levels of air pollution have been notoriously high in China's capital for years.

In 2008, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing started reporting the amounts of PM 2.5 matters, which are the smallest and most harmful airborne particulants that can be recorded in the atmosphere.

The Chinese government’s initial reaction was to criticize the initiative, and went so far as to order the embassy to stop reporting the figures.

He Xiaoxia, who heads the Beijing-based non-governmental organization Green Beagle, said, “At the beginning, the government kept saying that the U.S. Embassy figures were not accurate because one location in Beijing could not represent the whole of the city, and that is a scientific fact. But another important thing is that the common people needs to know the quality of the air where they live.”

In 2011, He Xiaoxia was using a machine to record the health effects of second-hand smoking. The same machine was able to monitor the amount of PM 2.5 in the atmosphere, so she decided to post that data online for people to share.

China Dialogue editor Xu Nan says that NGOs were a crucial tool to increase people's awareness of environmental issues, such as air quality.

“I remember how difficult it was in 2011 when I was trying to promote better understanding of the hazard of air pollution. I was having a very hard time trying to convene forums where journalists and common people could learn and understand the concept of PM 2.5,” she says.

But by the end of the year, she says, PM 2.5 became a matter of public knowledge.

In January, 2012, and after pressure from Beijing-based NGOs, the Beijing's municipal government started including the PM 2.5 into their data releases.

Earlier this week, China's populist newspaper, the Global Times, published a chart comparing the measurements done by the U.S. Embassy and those of the Beijing government. After explaining why the two measurements were slightly different, the article said that the goal of the official “Beijing's new Air Quality Index” - or AQI - was to make air pollution readings more transparent.

The newspaper says “It came after years of refusing to measure PM 2.5, hiding the true extent of air pollution.”

Ever since monitoring stations started recording alarming levels of toxic matter in Beijing and other cities' air last week, news outlets have run updates and published editorials on the extent of the problem, and on the government's response.

Worth the risk?

Much media attention focused on the so-called “Chinese mode of development” and questions whether the economic achievements reached in the past few decades were worth the risk of compromising people's health.

The People's Daily, flagship publication of the Communist Party, ran an editorial on Monday titled “A Beautiful China Starts with Healthy Breathing.” The piece urged government departments to change their ways in how they deal with environmental problems.

“Economic development cannot follow the old path of 'pollution first, fix later,'” the article read. “Urban management cannot face emergency with the old mentality of 'bad air is just a small thing'.”

Xu Nan is the Beijing-based managing editor of the website China Dialogue, which tracks coverage and provides commentary on environmental issues in China. She says that she witnessed a shift in how environmental news is reported.

“In the past, the thinking was that environmental concerns might have an impact on the speed of development, so the emphasis was put on the protection of development over the environment,” Xu says. Now, she says, things have turned around.

“Environmental problems have now become something that cannot be ignored,” adds Xu.

She says that a string of environmental controversies in 2012 has showed the government that it cannot afford to disregard people's demands.

“In one case after the other, the government has recently been discovering that if they do not respond to public opinion, then that increases their cost in managing the situation,“ Xu says.

More media coverage

As protests against polluting projects gain boldness in China, media have increased their coverage of the events and the government has become more responsive.

In 2012, people protested against projects such as a coal-fired plant in Haimen, a wastewater pipeline in Qidong and a chemical plant in Ningbo. In many cases, public demonstrations brought a delay in the development of the project and sometimes even halted it.

Part of the government response in facing environmental issues has been to allow less strict disclosure of relevant information.

Levels of air pollution have been notoriously high in China's capital for years.

In 2008, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing started reporting the amounts of PM 2.5 matters, which are the smallest and most harmful airborne particulants that can be recorded in the atmosphere.

The Chinese government’s initial reaction was to criticize the initiative, and went so far as to order the embassy to stop reporting the figures.

He Xiaoxia, who heads the Beijing-based non-governmental organization Green Beagle, said, “At the beginning, the government kept saying that the U.S. Embassy figures were not accurate because one location in Beijing could not represent the whole of the city, and that is a scientific fact. But another important thing is that the common people needs to know the quality of the air where they live.”

In 2011, He Xiaoxia was using a machine to record the health effects of second-hand smoking. The same machine was able to monitor the amount of PM 2.5 in the atmosphere, so she decided to post that data online for people to share.

China Dialogue editor Xu Nan says that NGOs were a crucial tool to increase people's awareness of environmental issues, such as air quality.

“I remember how difficult it was in 2011 when I was trying to promote better understanding of the hazard of air pollution. I was having a very hard time trying to convene forums where journalists and common people could learn and understand the concept of PM 2.5,” she says.

But by the end of the year, she says, PM 2.5 became a matter of public knowledge.

In January, 2012, and after pressure from Beijing-based NGOs, the Beijing's municipal government started including the PM 2.5 into their data releases.

Earlier this week, China's populist newspaper, the Global Times, published a chart comparing the measurements done by the U.S. Embassy and those of the Beijing government. After explaining why the two measurements were slightly different, the article said that the goal of the official “Beijing's new Air Quality Index” - or AQI - was to make air pollution readings more transparent.

The newspaper says “It came after years of refusing to measure PM 2.5, hiding the true extent of air pollution.”