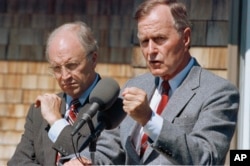

Newly declassified documents show that a quarter-century ago as worries were emerging over North Korea's nuclear ambitions, then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney told allies the U.S. should not consider military action because it could jeopardize diplomatic efforts.

Cheney would later serve as vice president to George W. Bush. He was a leading advocate of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq that toppled Saddam Hussein over fears he had weapons of mass destruction, which turned out not to be the case.

The North Korea debate is playing out again today with higher stakes, because the isolated nation could soon threaten the U.S. mainland with nuclear-tipped missiles. President Donald Trump has not ruled out using military force to stop it. Currently in Asia, Trump will be pressing China on Thursday to do more to rein in its wayward ally.

In 1991, when Cheney served as Pentagon chief for President George H.W. Bush, his outlook on how to deal with North Korea was very different from his later approach to Iraq.

Tactical nuclear arms pulled

With the Cold War over, the elder Bush had enacted a major change in military policy by withdrawing from the field all U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, including from South Korea. That offered an opening to secure North Korea's assent to agreements banning nuclear reprocessing and enrichment, and by extension nuclear weapons, from the peninsula.

Documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and published Wednesday by the National Security Archive at George Washington University provide insight into the U.S. diplomatic "game plan" to stop North Korea's nuclear weapons program.

Concerns had been growing in Washington over the North's nuclear capabilities. A reactor built in the mid-1980s offered it the means to produce plutonium that could potentially be used for bombs.

Among the documents is a briefing paper prepared for a December 1991 meeting of deputies in the National Security Council and other U.S. government agencies to discuss a U.S. strategy that offered progress toward dialogue and diplomatic normalization if the North allowed international safeguards and inspections.

The paper mentions potentially seeking sanctions if North Korea stalled, but it took one potential stick off the table. The briefing paper says Cheney had told leaders in U.S.-allied South Korea and Japan that the U.S. "should not consider 'military measures,' since such discussion could jeopardize our initial diplomatic strategy."

Greater threat

The threat posed by North Korea's nuclear and missile programs has grown substantially in the ensuing 26 years, and the outlook for diplomacy today is bleaker than it was then. North Korea is believed to have developed a small arsenal of bombs and has made rapid, recent strides toward perfecting a nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missile.

Trump has struck a more conciliatory tone than usual this week for a diplomatic resolution, although speaking Wednesday in the South Korean parliament he delivered a sharp warning to the rogue nation: "Do not underestimate us. And do not try us."

The documents reprise other themes that have become familiar in two decades of failed efforts to stop North Korea's weapons programs: doubts over China willingness to risk destabilizing its wayward neighbor; concerns that North Korea is negotiating in bad faith; and gaps in U.S. intelligence on the nuclear program.

At the end of 1991, the two Koreas did sign a declaration on denuclearization and the North reached a safeguards agreement with the U.N. nuclear watchdog. But hopes faded as suspicions grew that North Korea might be hiding parts of its nuclear weapons program from inspectors and how much plutonium it had processed.

Those concerns grew into a major crisis that led Washington to seriously consider military action against North Korea's nuclear facilities.

The suspicions were allayed when the U.S. and the North reached an aid-for-disarmament agreement in 1994 that lasted for nearly a decade but collapsed over the North's clandestine pursuit of uranium enrichment.