In a letter sent to President Barack Obama before his trip this week, Human Rights Watch called Vietnam a police state that has one of the most repressive governments in the world.

The U.S. leader saw the repression firsthand, with authorities rounding up activists just hours before he was set to meet with them.

“We do believe in certain universal values, and it’s important for us to speak out on behalf of those values wherever we go,” Obama said as he sat down Tuesday with six civil society members in Hanoi.

Hours after lodging his concern about Vietnam’s rights record, Obama boarded a plane and left for the next leg of his Asia trip, leaving some to question the effectiveness of this type of engagement in promoting reform.

But “it’s important for presidents to engage. These things can pay off in the long run. It takes a while before you see it,” said James Goldgeier, dean of the School of International Service at American University in Washington. “Regimes that don’t want to open up are not going to open up overnight.”

Spurring lasting change

One does not have to look much further back than the Cold War for an example of how U.S. engagement helped usher in an era of democracy.

Combining soft and hard power — the old carrot and stick method — was ultimately effective, Georgetown University diplomacy professor Cynthia Schneider said. And don’t discount the impact of cultural envoys, who fed an appetite for freedom in those living behind the Iron Curtain.

“Whether it was jazz music or rock 'n' roll, it kept their hope of freedom alive and kept them applying pressure to their own leaders,” Schneider said. “I think it was a brilliant combination of the two, and I would say the last time we have done that."

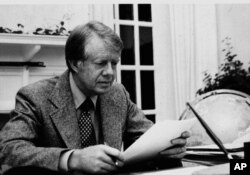

In the late 1970s, former President Jimmy Carter began what turned out to be strong push for democracy and human rights throughout the Americas, where many of the countries were run by military dictators.

“People derided him [Carter] at the time for being naïve and for making human rights such an important part of his foreign policy,” Goldgeier said. “But if you look at what happened over time in Central and South America, we have seen just an enormous change in democratization throughout the entire region.”

Pushing for reform

Obama’s approach in such matters has been nuanced.

The president is often quick to point out the United States is not perfect. He’s repeatedly said the United States is not seeking to impose its form of government on another nation.

“We respect Vietnam’s sovereignty and independence,” Obama said, standing alongside his Vietnamese counterpart in Hanoi. “At the same time, we will continue to speak out on behalf of human rights that we believe are universal, including freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion and freedom of assembly.”

The president, while pursuing stronger security or economic ties, has not shied away from pushing regimes toward change.

“Still incomplete” was the report card he gave to Myanmar’s democratization during a 2014 visit.

But in Myanmar, the United States was able to get on the side of change at a time when the Southeast Asian country’s military regime was already moving toward reform, said Thomas Carothers of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“We shouldn’t think of engagement per se as a lever that opens up societies," Carothers said. “It’s at best a complement to a domestic process that is usually driven for other reasons.”

Still, the frequent Foreign Policy magazine contributor emphasizes each country and each scenario is different.

“It can be lip service if there is no real follow through and it’s clearly just a symbolic measure to appease critics back home and possibly abroad,” Carothers said. “It can also be part of a more sustained engagement in which one comes back to these issues time and again with the government and really presses hard.”

Obama recently announced the United States would relax some sanctions against Myanmar, following the country’s November elections that solidified its transition from military rule to a democratic government.

The follow through

Just months after taking office, Obama made a bold move — reaching out to the Arab world, where relations were in tatters from the Iraq War.

“Obama’s speech in Cairo in 2009 — such a beautiful speech that inspired so many people — but there was not one cent put into follow-up,” Schneider noted. “On top of that, the United States has supported each successive Egyptian leader, including [Abdel Fattah el-]Sissi, who is far more repressive than [Hosni] Mubarak ever was, and we continue to support them simply so we can sell them our usual amount of arms, overriding human rights concerns.”

The mistake that is often made, said Schneider, a former U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands, is to define strategic interests too narrowly, focusing on engagement in order to satisfy security needs or economic ties.

“Our strategic interest is remaining a model admired and aspired to around the world for democracy and what all that means,” Schneider said. “We have completely lost that position in the Middle East. It does not exist.”

Despite the lack of follow through in countries like Egypt, Schneider credits the Obama administration for programs supporting young entrepreneurs around the world, particularly women, helping create job opportunities in countries where economic development is critical.

“It is in our strategic interest to have these countries that are very fragile states right now prosper," she said. "And that’s how they are going to be at peace.”