President Donald Trump once joked he could “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” and not lose voter support. The quip was intended as hyperbole to make a point on the loyalty of his base.

Now, Trump says, he has the power to keep himself out of jail if he wanted, declaring an “absolute right to PARDON myself.” This time, though, it seems he isn’t joking.

But there is a big limit in the world of presidential pardons: impeachment.

A look at what’s true and what’s not when it comes to presidential pardons:

So presidents get to do what exactly?

Under the Constitution, the president has the power to grant “reprieves and pardons” for federal (but not state) crimes, essentially wiping out a person’s convictions. The power is, as Trump says, “absolute” in that pardons can’t be overturned by Congress or the courts.

Almost every president has used his pardon powers, but somewhat narrowly, focusing on overturning cases when they believe a severe injustice has been done or is needed to heal partisan rifts.

President Andrew Johnson, for example, granted blanket pardons to soldiers who fought in the Confederate Army as a practical way of reuniting the nation following the Civil War. And President Gerald Ford in 1974 pardoned his predecessor, Richard Nixon, for all federal crimes Nixon “has committed or may have committed or taken part in” during his presidency, on the grounds that the nation had become too “polarized” and needed to move past the Watergate scandal.

The big exception

There is one notable exception to a president’s pardoning powers Trump doesn’t mention: cases of impeachment. Under the U.S. system of checks and balances, Congress can hold presidents accountable by ousting them using impeachment trials.

Only two presidents have been impeached by the House, although both were acquitted by the Senate: Johnson in 1868 after he clashed with Congress over reconstruction of the South and Bill Clinton in 1998 on charges of lying under oath and obstructing justice concerning his sexual relationship with Monica Lewinsky.

(Nixon avoided impeachment by resigning before the House could vote.)

The bottom line is that Trump retains his pardoning powers up until a possible impeachment. And considering that impeachment trials tend to be wildly partisan affairs, it is unlikely Trump would be ousted so long as the GOP still controls the House and Senate.

Pardons as a political weapon

A person doesn’t have to be convicted for a pardon to take place. That was the case in the Iran-Contra scandal, which involved the secret sales of weapons overseas by the Reagan administration.

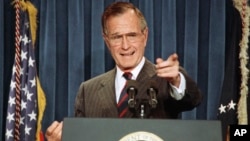

By the time the chief prosecutor in the case was prepared to present evidence of a high-level cover-up in court, President George H.W. Bush blocked the prosecution of several central figures using his pardoning power. The pardons infuriated the prosecutor, Lawrence Walsh, and the $47 million investigation resulted in only one person sent to prison.

Bush defended his pardons by saying “at the heart of this investigation was a political dispute between the executive and legislative branches over foreign policy. We must be careful not to criminalize constitutional disputes of this kind.”

Likewise, Trump could try to undercut the Russia investigation by pardoning anyone charged by special counsel Robert Mueller. Overall, 19 people have been charged in the investigation, including Trump’s former campaign chair and national security adviser.

But such pardons could also trigger impeachment trials in Congress on the claim that Trump was trying to obstruct justice. But again, the outcome would probably fall on party lines.

Could the president pardon himself?

So far, Trump has shown he’s not afraid to pardon others he claims were unfair victims of partisanship. Among those include Joe Arpaio, the former Arizona sheriff who clashed with a judge on immigration, and I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the Bush administration official convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice in the Valerie Plame leak case.

But could Trump pardon himself? Not surprisingly, that particular scenario has never been tested in the courts.

Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, says it wouldn’t happen anyway.

“Pardoning himself would be unthinkable and probably lead to immediate impeachment,” Giuliani told NBC’s Meet the Press this weekend.

According to the website HuffPost, Giuliani said the president was completely immune from prosecution and at one point offered this odd hypothetical:

“If he shot James Comey, he’d be impeached the next day,” he said. “Impeach him, and then you can do whatever you want to do to him.”

Comey is the former FBI director who was leading the Russia investigation when Trump fired him.