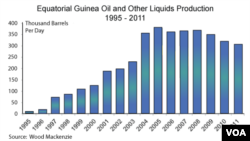

NAIROBI - When Equatorial Guinea discovered oil in the 1990s, the country was transformed forever from a sleepy former Spanish colony into an oil state.

The country's Gross Domestic Product growth was a staggering 71 percent in 1997, according to the International Monetary Fund, almost entirely on the back of oil revenues. By 2009, the country was earning more than $8 billion a year from the commodity.

But the wealth has only further enriched and entrenched Equatorial Guinea's authoritarian president Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who's held power for more than 30 years, while doing little to improve the lives of 685,000 citizens.

The country ranked 136 out of 187 countries last year on the United Nations Human Development Index. Other oil-producing countries, including Angola, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, rank even lower.

The head of the Africa Program at Chatham House in London, Alex Vines, says citizens lose out when African governments misuse oil revenues for consumption, rather than development.

"Prestige buildings, luxury goods, these have been really the kind of caricature of how countries have used this,” he says. “Gabon, for example, had the highest consumption of champagne in the world for a while, all funded by oil."

Managing expectations

A growing gap between rich and poor, rampant corruption and the tightening grip of authoritarian leadership are all symptoms of the so-called "resource curse," when a discovery that should benefit the population ends up doing more harm than good.

"The thing about oil and minerals is that very quickly, huge, fast flows of money come from these natural resources and the ability to manage that in a way that benefits citizens isn't always in place," says Brendan O'Donnell of the natural resources monitoring group Global Witness.

New oil finds in Kenya and the Ivory Coast and natural gas off the coast of Tanzania have generated a lot of excitement in recent months, with countries touting the discoveries as a point of pride.

“I think it's a bit like in the old days when each country wanted its own airlines,” says Vines of Chatham House. “Certainly reading some of the Kenyan press, some of the euphoria about Kenya now having oil was a bit worrying I think.”

Even countries that are relatively new to the oil game have shown some disconcerting behavior.

Uganda discovered oil in 2006 and is due to begin production in three to five years. But a lack of transparency in oil contracts is raising concerns the government is not acting in the people's best interests.

"There was a lot of talk and expectations last time, and the information available on the oil sector is not enough,” says Lawrence Bategeka, senior researcher at the Economic Policy Research Center in Kampala. “Not enough information is being released to the public."

Uganda's parliament has been seeking to force the government to disclose the details of oil contracts signed with international companies.

Bategeka says citizens are unhappy with the government's reluctance to cooperate.

"But of course government has an explanation,” he says. “When asked 'Why conceal information?' They allude to security concerns, but the public out there does not accept that as a good explanation."

Window of opportunity

Discovering oil is not like winning the lottery. The industry is sensitive to the whims of the international markets and demand from Europe, Asia and North America.

Chief economist and Vice President of the African Development Bank Mthuli Ncube says with current oil prices relatively high, oil-producing countries in Africa have done well in recent years, and recovered from losses suffered during the global financial crisis three years ago.

“But going forward,” he says, “with the softening of oil price, maybe even the slowdown of economic growth in China, that obviously could affect the growth prospects of the countries.”

In Angola, where the oil industry accounts for 90 percent of economic output, the government accumulated some $9 billion in contractor arrears during the peak of the financial crisis in 2009.

Ncube's first word of advice is to diversify.

He says economies must not become reliant on one commodity, noting progress in Nigeria, Africa's biggest oil exporter.

“[Nigeria's] been diversifying slowly but surely,” he says. “In the IT sector, services sector and agricultural sector, they're competing with the oil sector in terms of size and contribution.”

O'Donnell with Global Witness says resources management safeguards are not just about promoting social benefits, but also about making the most of an economic opportunity.

"These resources have a lifespan, they will run out at some point,” he says. “If your country misses the opportunity of benefiting from the resources, you can't get that back. You've lost that moment."

The country's Gross Domestic Product growth was a staggering 71 percent in 1997, according to the International Monetary Fund, almost entirely on the back of oil revenues. By 2009, the country was earning more than $8 billion a year from the commodity.

But the wealth has only further enriched and entrenched Equatorial Guinea's authoritarian president Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who's held power for more than 30 years, while doing little to improve the lives of 685,000 citizens.

The country ranked 136 out of 187 countries last year on the United Nations Human Development Index. Other oil-producing countries, including Angola, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, rank even lower.

The head of the Africa Program at Chatham House in London, Alex Vines, says citizens lose out when African governments misuse oil revenues for consumption, rather than development.

"Prestige buildings, luxury goods, these have been really the kind of caricature of how countries have used this,” he says. “Gabon, for example, had the highest consumption of champagne in the world for a while, all funded by oil."

Managing expectations

A growing gap between rich and poor, rampant corruption and the tightening grip of authoritarian leadership are all symptoms of the so-called "resource curse," when a discovery that should benefit the population ends up doing more harm than good.

"The thing about oil and minerals is that very quickly, huge, fast flows of money come from these natural resources and the ability to manage that in a way that benefits citizens isn't always in place," says Brendan O'Donnell of the natural resources monitoring group Global Witness.

New oil finds in Kenya and the Ivory Coast and natural gas off the coast of Tanzania have generated a lot of excitement in recent months, with countries touting the discoveries as a point of pride.

“I think it's a bit like in the old days when each country wanted its own airlines,” says Vines of Chatham House. “Certainly reading some of the Kenyan press, some of the euphoria about Kenya now having oil was a bit worrying I think.”

Even countries that are relatively new to the oil game have shown some disconcerting behavior.

Uganda discovered oil in 2006 and is due to begin production in three to five years. But a lack of transparency in oil contracts is raising concerns the government is not acting in the people's best interests.

"There was a lot of talk and expectations last time, and the information available on the oil sector is not enough,” says Lawrence Bategeka, senior researcher at the Economic Policy Research Center in Kampala. “Not enough information is being released to the public."

Uganda's parliament has been seeking to force the government to disclose the details of oil contracts signed with international companies.

Bategeka says citizens are unhappy with the government's reluctance to cooperate.

"But of course government has an explanation,” he says. “When asked 'Why conceal information?' They allude to security concerns, but the public out there does not accept that as a good explanation."

Window of opportunity

Discovering oil is not like winning the lottery. The industry is sensitive to the whims of the international markets and demand from Europe, Asia and North America.

Chief economist and Vice President of the African Development Bank Mthuli Ncube says with current oil prices relatively high, oil-producing countries in Africa have done well in recent years, and recovered from losses suffered during the global financial crisis three years ago.

“But going forward,” he says, “with the softening of oil price, maybe even the slowdown of economic growth in China, that obviously could affect the growth prospects of the countries.”

In Angola, where the oil industry accounts for 90 percent of economic output, the government accumulated some $9 billion in contractor arrears during the peak of the financial crisis in 2009.

Ncube's first word of advice is to diversify.

He says economies must not become reliant on one commodity, noting progress in Nigeria, Africa's biggest oil exporter.

“[Nigeria's] been diversifying slowly but surely,” he says. “In the IT sector, services sector and agricultural sector, they're competing with the oil sector in terms of size and contribution.”

O'Donnell with Global Witness says resources management safeguards are not just about promoting social benefits, but also about making the most of an economic opportunity.

"These resources have a lifespan, they will run out at some point,” he says. “If your country misses the opportunity of benefiting from the resources, you can't get that back. You've lost that moment."