Some would describe it as mission impossible.

Trying to run a government is challenging enough, but when you are coming under round-the-clock airstrikes, seeing members of your Cabinet killed and having to shift your location frequently to escape death in a scorched-earth war zone where you command no fighters, the odds of success would seem to be heavily stacked against you.

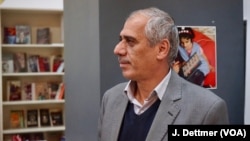

That isn’t a view held by politically independent heart surgeon Jawad Abu Hatab. Five months ago, he was elected prime minister of the Syrian Interim Government, or SIG, by an overwhelming majority of members of a general assembly of the war-wracked country’s main exiled political opposition groups.

Since his election, airstrikes have killed 10 members of Syria’s little-known "alternative government" — two of them ministers; but, the 54-year-old cardiologist from rural Damascus remains — outwardly anyway — undaunted. Hatab smiles when he explains how he and his wife, also a doctor, handled 26 births in a makeshift clinic one night as fighting raged around them.

“Twelve of them were by Cesarean Section,” he told VOA in an interview in the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep. He had just come from northern Syria — a perilous journey in itself — for a 24-hour visit to Turkey to meet with non-governmental organizations.

Legitimate alternative?

The interim government has struggled to not only be relevant, but to be accepted as a legitimate alternative to the regime of Syrian President Bashar-al Assad. The interim government was formed in 2013 by an opposition umbrella alliance now known as the Syrian National Coalition.

Rebel commanders, whether aligned to the moderate Free Syrian Army (FSA) or running hardline Islamist brigades, have paid neither it nor the Syrian National Coalition much heed. Local councils in rebel-controlled areas have gone their own way and without any grassroots organizational structure inside Syria, and starved of funds, the interim government has been little more than a talking shop of political exiles or a stage for factional squabbles.

In a poll last year conducted in Syria by the NGO the Day After Association, only 6.5 percent of respondents said the interim government represented their interests. That was a lower percentage than what the armed factions or even the Assad government received at 14.5 percent and 16.1 percent respectively. The Western- and Gulf-backed Syrian National Coalition received the support of 16.8 percent. A quarter of respondents said no one represented them.

Helping those in need

Hatab, the interim government's third prime minister, wants to change that and is determined to make his alternative government relevant to the more than five million Syrians living in rebel-controlled areas. His focus is on practical steps, including having all ministers based inside Syria and working on establishing education and health care services. He and his ministers are based in Aleppo and Idlib provinces but often move their locations because of fighting or airstrikes.

He lists statistics, saying 28,000 children have been killed in the nearly-six-year-long conflict and 120,000 injured. Of the 1.5 million children in opposition-held areas, there are facilities left only to teach 700,000. He says 2,400 schools have been destroyed. Under Hatab's plan, he needs 30,000 teachers, but only 8,000 are now teaching on salaries of $100 a month. He needs 5 million school books and the interim government is now busy recycling old textbooks and photocopying others for distribution.

Hatab and his ministers are busy negotiating with the European Union — he is asking Brussels for $88 million for various projects. He wants to rotate doctors and medical staff in and out of Syria and says the clinics left need more drugs and equipment.

Hatab says trying to exert influence over the armed factions at this stage as his predecessors attempted is a waste of time and will merely get the SIG bogged down in fruitless negotiations. “We will try to negotiate with all the militias after we have established services for the civilians,” he says, arguing then he will have more leverage, if he has popular support.

“For years the fighters have referred to the interim government as the ‘hotel government,’ saying that all the opposition politicians just live comfortably in hotels in Turkey. With me they can’t do that — I am inside Syria,” he says. The heart surgeon has been from the very start of the conflict. Hatab estimates he has carried out more than 5,000 operations in the past five years as he has moved around the country to where the need is most.

Hatab acknowledges not having command of the armed factions does pose challenges but says the militias are giving him the political space to get on with what he wants to do, including Ahrar al-Sham, a hardline Islamist militia that’s been in alliance with Jabhat Fatah al-Sham, the al-Qaida-linked group once known as Jabhat al-Nusra. The latter, he says, is unable to confront him currently because that will bring them into confrontation with other militias that are supportive of what the SIG under his leadership is trying to do — namely, benefit civilians in ways that may improve their lives even in the midst of a war.

“Others, too, working with more than 400 local councils in Syria’s opposition areas also report that militias have become easier to work with and that many armed factions are backing off insisting that they have control over civilian as well as military affairs.”

More resources needed

For Hatab’s approach to work — for him to be able to bring more political coherence to an uprising that’s been marked by disunity and factional and ideological disputes and was quickly dominated by militias and the emergence of toxic jihadist groups — he will need more resources from Western powers and a willingness to back a revolution that is in its darkest and possibly final days.

The question is, has he come too late?

“He has good ideas,” says a Western diplomat. “But he has no traction and we are probably now in the end game,” added the diplomat, who asked not to be identified in this article. Much will depend on President-elect Donald Trump. Shortly after his election earlier this month, Trump told The Wall Street Journal that, once in office, he would consider cutting off funding for the Syrian rebels and that the priority in Syria should be to defeat the Islamic State terror group rather than oust Assad.

“I think Trump doesn’t know a lot about what is going on in Syria,” says Hatab. “Once he’s in office and understands what’s happening here, that Russian and Assad warplanes have bombed more than 200 hospitals, once he has accurate information, I hope he will change his mind.”

What does Hatab want from a Trump presidency? “At the very least, to stop the airstrikes on us and impose a no-fly zone,” he says. Whether he will get to make a face-to-face plea to Trump or top level administration officials remains unclear. Hatab hopes to be in the United States by November 29 for a private donor conference but so far, has received no reply to a visa application he filed more than two weeks ago.